Celestial Rhythms: Unpacking the Enduring Wisdom of Native American Tribal Lunar Calendars

For millennia, long before the imposition of the Gregorian calendar, Indigenous peoples across North America meticulously charted the passage of time not by the sun’s distant reign, but by the intimate, ever-changing face of the moon. These traditional moon-based time-keeping systems, known as tribal lunar calendars, were far more than mere chronological tools; they were intricate tapestries woven from astronomical observation, ecological knowledge, spiritual belief, and the practical necessities of survival. They dictated when to plant, when to hunt, when to gather, and when to celebrate, embodying a profound and reciprocal relationship with the natural world that continues to resonate today.

Unlike the solar-centric Gregorian calendar, which rigidly divides the year into twelve months of fixed days, Native American lunar calendars typically followed the approximately 29.5-day cycle of the moon. This meant a year comprised roughly 12 to 13 lunar cycles, or "moons." The discrepancy between 12 lunar cycles and a full solar year often led to a "thirteenth moon" or an adjustment period, a flexible approach that allowed for alignment with seasonal changes. This adaptability underscored a fundamental difference in worldview: time was not a linear, abstract construct, but a living, breathing phenomenon intrinsically linked to the Earth’s rhythms.

The names given to each moon varied widely among the hundreds of distinct tribes, reflecting the specific environment, flora, fauna, and cultural practices of each nation. These names were vivid, poetic, and profoundly practical, serving as mnemonic devices for the activities and natural events characteristic of that particular period. For instance, many Algonquian-speaking tribes, such as the Anishinaabe (Ojibwe), observed the "Makwa Giizis" (Bear Moon) in late winter when bears emerged from hibernation, or the "Manoominike-Giizis" (Wild Rice Moon) in late summer when the crucial wild rice harvest occurred. The Lakota of the Great Plains recognized "Wipata Wi" (Drying Moon) in late summer, signaling the time to preserve meat and berries, and "Canwapegi Wi" (Leaf-Falling Moon) as autumn progressed.

These moon names were not arbitrary; they were encyclopedias of ecological knowledge. The "Strawberry Moon" (common among many Eastern Woodland tribes) marked the ripening of wild strawberries, a vital food source. The "Hunger Moon" or "Starving Moon" (often in February) spoke to the leanest time of winter, when food stores dwindled and hunting was most challenging. The "Sucker Fish Moon" indicated the spawning season for certain fish, while the "Corn Planting Moon" guided agricultural communities on the optimal time for sowing. Each name was a lesson, a reminder, and a directive, ensuring the community remained attuned to the subtle shifts in their environment.

"Our calendar was written in the land itself, in the behavior of animals, the budding of plants, the flow of water, and the changing face of the Grandmother Moon," one elder explained, emphasizing the holistic nature of this time-keeping. "We didn’t just tell time; we lived time, we felt it in our bones and in the earth beneath our feet." This profound connection fostered a sustainable lifestyle, as communities learned to live in harmony with the land’s cycles, taking only what was needed and respecting the renewal of resources.

The thirteen-moon cycle also held deep spiritual and philosophical significance for many tribes. The number thirteen itself is sacred in many Indigenous traditions, often associated with female cycles, cosmic balance, and the natural world’s complete annual rotation. The moon, often referred to as "Grandmother Moon" or "Old Woman Moon," was revered as a powerful feminine deity, a bringer of tides, a guardian of women’s cycles, and a gentle guide in the darkness. Her phases – new, crescent, half, full, waning – were seen as a metaphor for life’s journey: birth, growth, maturity, and decline, leading to renewal. Ceremonies and rituals were often timed to specific moon phases, reinforcing the spiritual connection between humanity and the cosmos.

The knowledge embedded in these calendars was not written down in books but passed orally from generation to generation through stories, songs, and direct observation. Elders, wisdom keepers, and spiritual leaders were the living libraries of this knowledge, sharing it with younger generations through experiential learning. Children learned to read the moon, the stars, the plants, and the animals as their primary textbooks, understanding that their survival and well-being depended on this intimate understanding. This oral tradition ensured that the calendar was a dynamic, living system, adaptable to subtle long-term climate shifts and local variations.

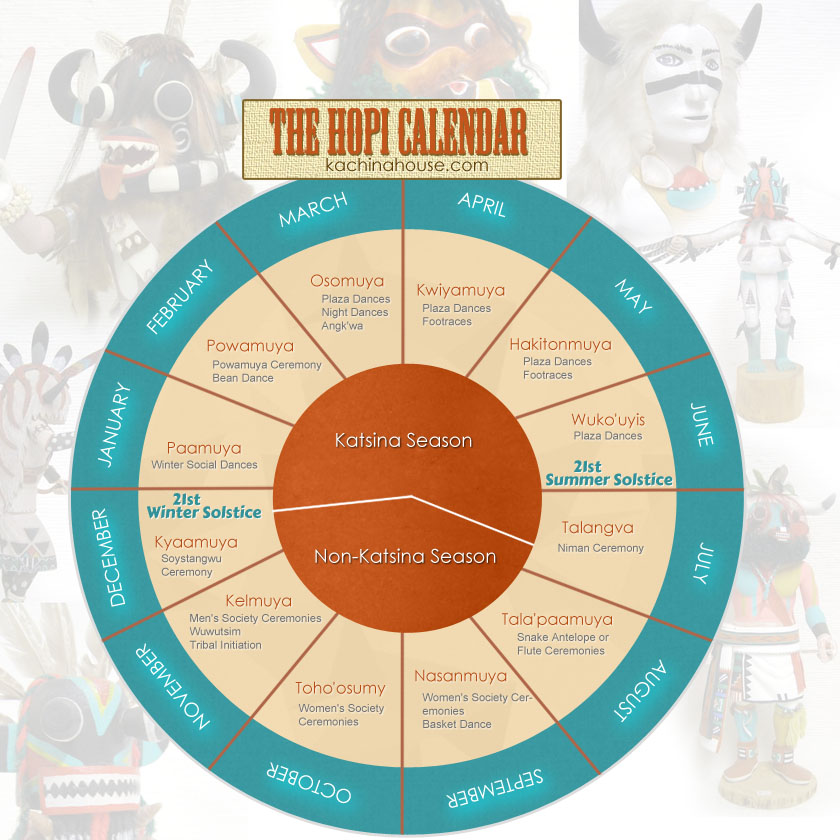

While sharing common principles, the diversity of Native American lunar calendars is a testament to the unique adaptations of each tribal nation. The Pueblo peoples of the Southwest, for instance, often integrated solar observations with lunar cycles, creating sophisticated systems that accounted for both solstices and equinoxes alongside the moon’s phases, reflecting their agricultural dependence and their architecture aligned with celestial events. The Cherokee, whose writing system (syllabary) was developed by Sequoyah, also had a detailed thirteen-moon calendar, with names like "Anagali" (Cold Moon) for January and "Kagali" (Bone Moon) for February, reflecting the scarcity of food and the need to rely on stored provisions.

The arrival of European colonizers brought a devastating disruption to these traditional systems. The imposition of the Gregorian calendar, Christian holidays, and a foreign concept of linear time was part of a broader effort to assimilate Indigenous peoples and erase their cultural identities. Children were sent to boarding schools where they were forbidden to speak their languages or practice their traditions, severing the intergenerational transmission of vital knowledge. Land theft, forced relocation, and the decimation of traditional food sources further eroded the practical utility and spiritual significance of the lunar calendars.

Despite these immense pressures, the traditional lunar calendars endured. They persisted in quiet whispers, in the continued practice of ceremonies, in the naming of children, and in the enduring wisdom of elders. Today, there is a powerful and growing movement among Native American nations to revitalize and reclaim these ancestral time-keeping systems. This revitalization is not merely an academic exercise; it is a profound act of cultural resilience, self-determination, and environmental stewardship.

Tribal communities are re-teaching their languages, reconnecting with traditional ecological knowledge, and re-establishing ceremonies timed by the moon. Schools are incorporating traditional calendars into their curricula, ensuring that future generations understand their heritage. The "Wolf Moon" or "Strawberry Moon" are no longer just quaint names; they are gateways to understanding ancient lifeways, sustainable practices, and a deep spiritual connection to the land.

In a world increasingly disconnected from natural rhythms, the wisdom of Native American tribal lunar calendars offers a compelling alternative. They remind us that time is not just a ticking clock but a cyclical journey, a dance between Earth and sky. They teach us the importance of observation, patience, and living in harmony with our environment. As we face global challenges like climate change, the lessons embedded in these ancient moon-based systems — of reciprocal relationships, deep ecological understanding, and living sustainably – are more relevant and urgent than ever. The Grandmother Moon continues her patient vigil, and in her cycles, the echoes of ancestral wisdom endure, offering guidance for a more balanced and respectful future.