The Unholy Dawn: Sand Creek Massacre – A Scourge on America’s Conscience

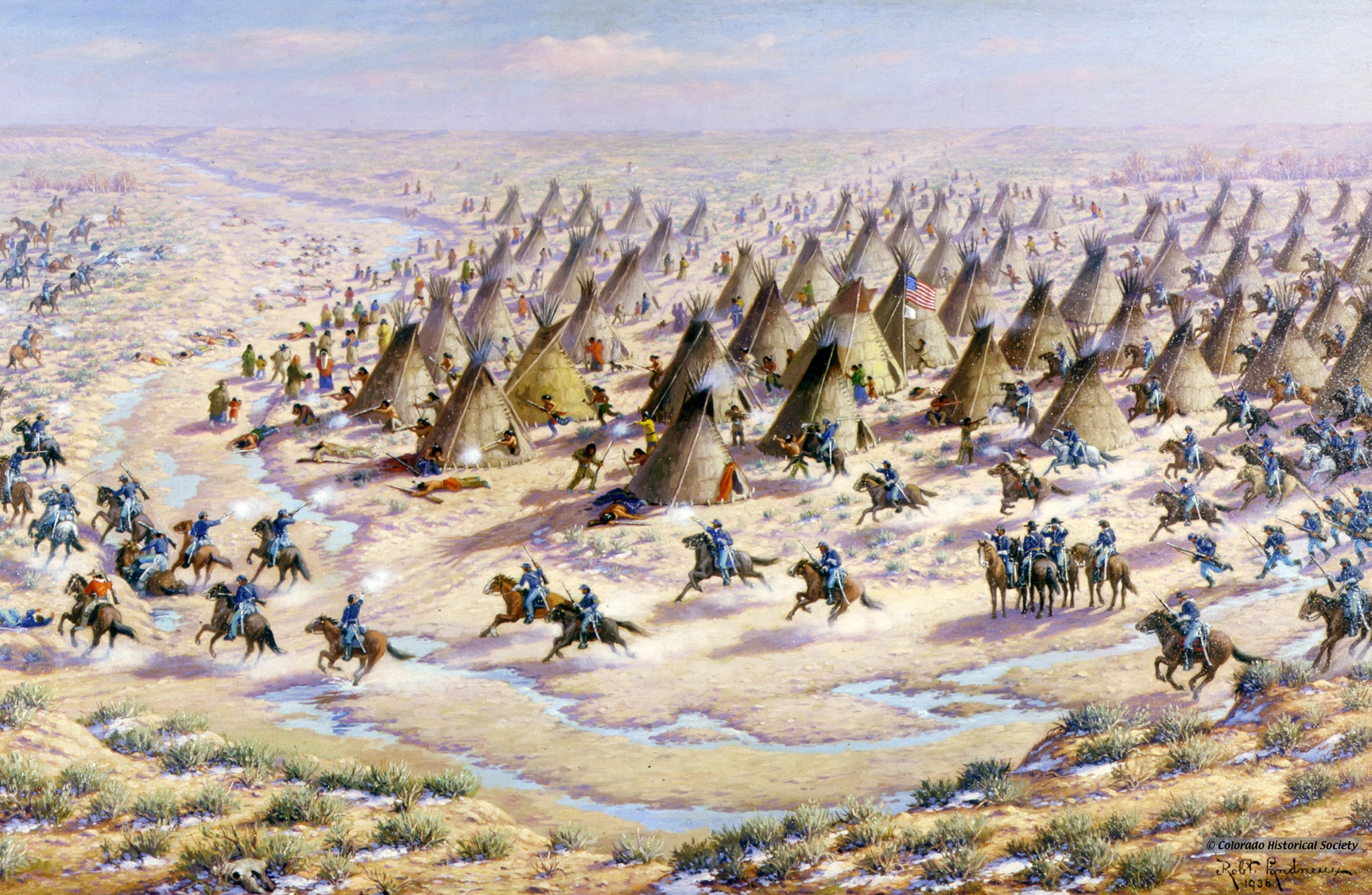

SAND CREEK, Colorado Territory – November 29, 1864. The pre-dawn chill hung heavy over the sleeping encampment of Cheyenne and Arapaho people. Above their tipis, two flags fluttered in the crisp autumn air: a large American flag, gifted by a U.S. Army officer as a symbol of peace, and beneath it, a smaller white flag, universally recognized as a sign of surrender and non-combatant status. Inside, Chief Black Kettle, a leader renowned for his unwavering commitment to peace, rested, believing his people were under the protection of the U.S. government.

What unfolded next was not an act of war, but an atrocity that would forever stain the fabric of American history. As the sun began to paint the eastern horizon, an estimated 700 heavily armed U.S. volunteer cavalrymen, under the command of Colonel John Chivington, descended upon the unsuspecting village. Their mission, self-proclaimed and ruthlessly executed, was not to engage in battle, but to annihilate. The Sand Creek Massacre, as it came to be known, was a barbarous act of unprovoked violence against a peaceful community, predominantly women, children, and the elderly, leaving an indelible mark of betrayal and horror.

A Powder Keg in the Plains

To understand the tragedy of Sand Creek, one must first grasp the volatile environment of the American West in the mid-19th century. The discovery of gold in the Colorado Territory in 1858 ignited the Pike’s Peak Gold Rush, drawing thousands of prospectors and settlers onto lands traditionally occupied by Native American tribes. The concept of "Manifest Destiny" fueled a relentless westward expansion, often at the expense of indigenous peoples, whose ancient claims to the land were systematically undermined by treaties, broken almost as soon as they were signed.

The Fort Wise Treaty of 1861, for instance, forced the Cheyenne and Arapaho to cede vast territories, confining them to a fraction of their ancestral lands along Sand Creek. Many tribal members, including Chief Black Kettle, reluctantly signed, hoping to avoid further conflict. Others, known as the "Dog Soldiers," refused to acknowledge the treaty, leading to a period of sporadic raids and retaliations that escalated tensions across the plains.

By 1864, the situation was a powder keg. Governor John Evans of the Colorado Territory, a staunch advocate for westward expansion, issued a proclamation authorizing citizens to "kill and destroy" all hostile Indians. This inflammatory rhetoric, coupled with a general fear and resentment among white settlers, created an atmosphere ripe for violence.

However, not everyone shared this belligerent stance. Major Edward Wynkoop, commander of Fort Lyon, believed in a peaceful resolution. He had met with Black Kettle and other chiefs at the Camp Weld Council in Denver in September 1864, where the Native leaders reiterated their desire for peace and their willingness to cooperate with the U.S. government. Wynkoop assured them that if they returned to their designated camp near Fort Lyon and lived peacefully, they would be protected. It was this assurance that led Black Kettle’s band to settle at Sand Creek, flying the American flag as a clear sign of their peaceful intentions.

Chivington’s Ambition and Apathy

Colonel John Chivington, a former Methodist minister turned military officer, held a starkly different view. A man of considerable ambition and unyielding prejudice, Chivington saw no place for Native Americans in the future of the West. His infamous declaration, "Nits make lice," succinctly encapsulated his philosophy: even children of hostile tribes should be eradicated to prevent future threats. He dismissed Wynkoop’s peace efforts, viewing them as weakness, and harbored political aspirations that he believed would be bolstered by a decisive military victory against Native Americans.

Despite being informed by Major Wynkoop of the peaceful intentions and location of Black Kettle’s camp, Chivington harbored no doubts about his plan. He deliberately circumvented Wynkoop, marching his troops from Denver on a secret mission to Sand Creek. His command consisted primarily of the 1st and 3rd Colorado Cavalry, composed of inexperienced volunteers whose enlistments were nearing an end. A "victory" was perhaps seen as a way to send them home as heroes.

The Horror of November 29th

At dawn on November 29, 1864, Chivington’s troops surrounded the unsuspecting village. Black Kettle, hearing the approaching hooves and the shouts, quickly hoisted the American flag and then the white flag, believing these symbols would guarantee his people’s safety. He urged his people not to flee, confident that the soldiers would recognize their peaceful status.

His faith was tragically misplaced. The cavalrymen, many reportedly intoxicated, charged into the camp, unleashing a torrent of gunfire and violence. The sight of women and children, not warriors, did not deter them. Eyewitness accounts from soldiers who later testified against Chivington painted a horrifying picture.

Lieutenant Silas Soule, who refused to allow his company to fire on the innocent, later recounted the scene: "The women and children were screaming and running in every direction… were killing them as fast as they could load their guns." He described how men, women, and children were scalped, their bodies mutilated. "I saw one squaw cut open and a child taken from her," Soule testified, describing the gruesome details of the soldiers’ barbarity.

Another witness, Captain Joseph Cramer, testified that he saw "a little child, probably three years old, that was scalped." He added that "the scalps of these Indians were stuck on poles, or carried on the saddles of the soldiers." The atrocities were not random acts but systematic brutality. The flags of peace and surrender were ignored, becoming ironic symbols of betrayal. Estimates of the dead range from 150 to 200, with an overwhelming majority—approximately two-thirds—being women, children, and the elderly. Only a handful of warriors were among the slain.

Investigations and Condemnation

Chivington initially returned to Denver a hero, his men displaying scalps and other gruesome trophies. But the truth of Sand Creek could not be suppressed for long. Reports from officers like Major Wynkoop and Lieutenant Soule, who were appalled by the massacre, began to surface, challenging Chivington’s narrative of a heroic battle against hostile warriors.

The courageous testimony of Silas Soule, who risked his career and his life to expose the truth, was pivotal. Tragically, Soule was murdered in Denver just months after testifying, a crime widely believed to be an act of retaliation for his whistleblowing.

The outrage eventually led to multiple federal investigations: one by a military commission, and two by Congress, including the influential Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War. Their findings were unequivocal and damning. The Joint Committee’s report declared that the attack was "a foul and dastardly massacre, which would have disgraced the veriest savages." It concluded that Chivington had "deliberately planned and executed a foul and dastardly massacre which would have disgraced the veriest savage among those who were the victims of his cruelty."

While Chivington was forced to resign from the military and his reputation was forever tarnished, he was never criminally prosecuted for his actions. The legal system of the time offered little recourse for justice for Native American victims, and Chivington successfully evaded accountability under military law by resigning before charges could be officially pressed.

A Lasting Legacy of Betrayal

The Sand Creek Massacre stands as a stark testament to the moral failures of unchecked power, racial hatred, and military misconduct. Its immediate aftermath saw an intensification of the Plains Wars, as enraged Cheyenne and Arapaho warriors, along with their Lakota allies, sought vengeance for the slaughter of their kin. The trust between Native American tribes and the U.S. government was shattered, leading to decades of brutal conflict and further displacement.

Today, the Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site in Kiowa County, Colorado, serves as a solemn memorial and a place of reflection. Established in 2007, it ensures that the memory of those who perished, and the lessons learned from this dark chapter, are never forgotten. It is a powerful reminder that history must be confronted honestly, even its most uncomfortable truths.

The story of Sand Creek is not just a historical footnote; it is a foundational narrative in understanding the complex and often tragic relationship between the United States and its indigenous peoples. It highlights the devastating consequences when humanity gives way to prejudice, and when the pursuit of land and power overshadows the fundamental rights to life and peace. The flags of peace and protection that Black Kettle raised that cold November morning remain, to this day, potent symbols of a promise tragically broken, a betrayal etched deeply into the American conscience.