Okay, here is a 1200-word journalistic article in English about the history of the Kumeyaay Tribe in Southern California.

Echoes of the Land: The Enduring History of the Kumeyaay Nation

SAN DIEGO, California – From the sun-drenched beaches of the Pacific to the arid expanses of the Anza-Borrego desert, and stretching deep into Baja California, Mexico, the land bears witness to an ancient legacy. This is the ancestral home of the Kumeyaay people, a vibrant Indigenous nation whose history in Southern California spans millennia, a narrative woven with deep cultural roots, profound resilience, and an unwavering connection to their ancestral lands despite centuries of invasion, displacement, and division.

The Kumeyaay story is not merely one of survival, but of enduring presence and revitalization. Their journey through time – from thriving pre-colonial societies to the brutal impact of Spanish missions, Mexican rule, and American annexation, culminating in a modern era of cultural resurgence and sovereign self-determination – offers a powerful testament to the strength of Indigenous peoples in the face of relentless adversity.

The Deep Roots: A World Before Contact

For over 10,000 years, the Kumeyaay (also known as Iipay, Tipay, and Kamia depending on dialect and geographical region) have inhabited this diverse landscape. Before the arrival of Europeans, their sophisticated hunter-gatherer society flourished, built upon an intimate understanding of their environment. Their territory was vast, encompassing what is now San Diego County, parts of Imperial County, and extending south into northern Baja California.

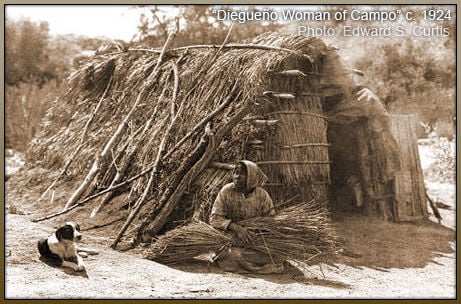

Life was meticulously organized around the seasons and the abundance of the land. Acorns, processed into a nutrient-rich meal, formed a dietary staple, supplemented by seeds, fruits, deer, rabbits, and an array of coastal marine life. Their knowledge of plant medicine was extensive, passed down through generations. Settlements were strategically located near water sources, often consisting of domed, brush-covered homes.

Social structures were complex, based on autonomous yet interconnected bands or clans, each with its own leadership, territory, and spiritual practices. Trade networks were extensive, reaching far inland to the Colorado River and along the coast, facilitating the exchange of goods like shells, obsidian, and ceramics. Their spiritual life was rich, characterized by ceremonies, rock art, and a profound reverence for the natural world, seeing themselves not as owners of the land, but as its caretakers.

As one Kumeyaay elder eloquently put it, "Our ancestors didn’t just live on the land; they were the land. Every mountain, every river, every plant held a story, a teaching, a spirit." This deep, symbiotic relationship would soon face an existential threat.

The Cataclysm: Spanish Invasion and the Mission System (1769-1821)

The year 1769 marked a cataclysmic turning point. The arrival of the Spanish expedition, led by Gaspar de Portolá and Father Junípero Serra, brought with it the establishment of Mission San Diego de Alcalá – the first of California’s 21 missions. What the Spanish called "progress" and "civilization," the Kumeyaay experienced as invasion, enslavement, and cultural genocide.

The mission system was designed to forcibly convert Indigenous peoples to Catholicism, assimilate them into Spanish society, and exploit their labor. Kumeyaay people were rounded up, often by force, and compelled to live at the mission, where they faced brutal discipline, disease, and the suppression of their language, spiritual practices, and traditional way of life. Diseases like smallpox and measles, to which Indigenous populations had no immunity, decimated their numbers, sometimes wiping out entire villages.

Yet, the Kumeyaay did not passively accept their fate. Their resistance was fierce and often strategic. In 1775, just six years after the mission’s founding, a coalition of Kumeyaay bands launched a daring revolt, burning down Mission San Diego de Alcalá and killing Father Luis Jayme. This act of defiance, though met with harsh Spanish retribution, sent a clear message: the Kumeyaay would not surrender their sovereignty without a fight. It remains a powerful symbol of their indomitable spirit.

"The 1775 revolt wasn’t just an act of violence; it was a desperate plea for freedom, a fight to protect our way of life from utter destruction," says Stan Rodriguez, a respected Kumeyaay cultural practitioner and educator. "It showed that even in the face of overwhelming power, our people would resist."

A New Yoke: Mexican Rule and the American Frontier (1821-1848)

With Mexico’s independence from Spain in 1821, the missions were secularized in the 1830s. However, this transition did not bring relief or the return of ancestral lands to the Kumeyaay. Instead, former mission lands were often granted to Mexican citizens, forming vast ranchos that further encroached upon Indigenous territories. The Kumeyaay continued to face exploitation, violence, and the erosion of their traditional land base.

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848, ending the Mexican-American War, ceded California to the United States. This ushered in yet another era of profound disruption. For the Kumeyaay, it meant a new set of colonizers, new laws, and a new, arbitrary line drawn across their ancient lands: the U.S.-Mexico border.

The American Divide: Reservations, Erasure, and Resilience (1848-1900s)

The American period brought increased pressure. The California Gold Rush led to a massive influx of settlers, escalating conflicts and violence against Native Americans. California’s statehood in 1850 was followed by laws that systematically dispossessed Indigenous peoples of their land and rights. Vigilante groups and state militias perpetrated horrific massacres, driving many Kumeyaay further into remote, less desirable areas.

The U.S. government’s response was the establishment of Indian reservations – small, fragmented parcels of land, often on the poorest soil, that further fractured traditional territories and communities. For the Kumeyaay, this meant the creation of 13 federally recognized reservations in San Diego County, including Barona, Campo, Capitan Grande, Ewiiaapaayp (Cuyapaipe), Inaja-Cosmit, Jamul, La Jolla, Manzanita, Mesa Grande, San Pasqual, Santa Ysabel, Sycuan, and Viejas. Each became a testament to survival, but also a constant reminder of lost lands.

Crucially, the U.S.-Mexico border carved through the heart of Kumeyaay territory, physically separating families and communities that had once moved freely across their ancestral lands. This artificial division continues to impact the Kumeyaay people today, making it challenging for relatives to visit, participate in ceremonies, and maintain cultural continuity. "The border is an artificial line drawn across our family," laments a Kumeyaay leader, expressing the pain of this imposed separation.

The late 19th and early 20th centuries also saw the devastating policy of forced assimilation through Indian boarding schools. Kumeyaay children were taken from their families, forbidden to speak their language, practice their traditions, or wear their traditional clothing. The aim was to "kill the Indian to save the man," a policy that inflicted intergenerational trauma but failed to extinguish the Kumeyaay spirit. Many elders secretly preserved their language and culture, passing it down quietly to ensure its survival.

Reclaiming and Revitalizing: The Modern Kumeyaay Nation

Despite centuries of systemic oppression, the Kumeyaay people have not only survived but are thriving. The late 20th and 21st centuries have witnessed a powerful resurgence of Kumeyaay culture, language, and sovereignty.

Today, the 13 federally recognized Kumeyaay bands in the U.S. are sovereign nations, each with its own elected tribal government. Through self-determination and strategic economic development – particularly through gaming enterprises like casinos – many Kumeyaay tribes have achieved a degree of economic independence that allows them to invest in their communities. These revenues support tribal services, healthcare, education, housing, and cultural preservation initiatives that were once unimaginable.

Cultural revitalization is at the forefront. Language immersion programs are teaching younger generations the Kumeyaay language, which faced near extinction. Traditional arts like basket weaving, pottery, and bird singing are experiencing a renaissance. Ceremonies and traditional gatherings are openly practiced, strengthening community bonds and spiritual connections to the land.

The Kumeyaay are also fierce advocates for their ancestral lands and environmental protection. They are at the forefront of opposing development projects that threaten sacred sites or natural resources, ensuring their voice is heard in land-use decisions. They actively work to bridge the U.S.-Mexico border, maintaining vital cultural ties with their Kumeyaay relatives in Baja California.

"We are not just a history; we are a future," says Erica Pinto, Chairwoman of the Jamul Indian Village of California. "Our ancestors endured so we could be here today, to rebuild, to teach, to thrive. Our story is one of unwavering strength and a deep commitment to who we are as Kumeyaay people."

The history of the Kumeyaay in Southern California is a profound testament to their endurance. It is a story etched into the very landscape they have called home for millennia – a narrative of deep spiritual connection, devastating loss, fierce resistance, and an ongoing, vibrant resurgence that continues to shape the future of this ancient and resilient nation. Their voices, once silenced, now echo across the land, strong and clear, ensuring that the legacy of the Kumeyaay will continue for generations to come.