The Unconquered Spirit: Native American Strategies for Survival in the Colonial Era

The arrival of European colonizers in the Americas ushered in an era of unprecedented upheaval for the Indigenous peoples who had thrived on the continent for millennia. Faced with devastating diseases, relentless land hunger, and alien cultural impositions, Native American nations were far from passive victims. Instead, they forged a complex and dynamic array of strategies for survival, demonstrating remarkable resilience, ingenuity, and a fierce determination to preserve their ways of life. From armed resistance to intricate diplomacy, cultural adaptation to spiritual revitalization, their responses carved a legacy of endurance that continues to resonate today.

The colonial encounter was, at its heart, a struggle for existence. European diseases, against which Native populations had no immunity, often preceded or accompanied the physical arrival of settlers, decimating communities and destabilizing societies. Smallpox, measles, influenza, and typhus swept through the continent, sometimes wiping out 90% or more of a population. This demographic catastrophe fundamentally altered the balance of power, yet it also compelled survivors to adapt, consolidate, and redefine their social structures. Historian Alfred Crosby famously termed this "biological warfare" – unintentional, perhaps, but devastating nonetheless.

The Spear and the Shield: Military Resistance

Perhaps the most visible and dramatic strategy for survival was outright military resistance. From the earliest encounters, Native Americans fought to defend their lands, sovereignty, and people. This was not a monolithic, unified struggle but a series of localized and regional conflicts, each with its own motivations and tactics.

In the early 17th century, the Powhatan Confederacy, under the leadership of Chief Wahunsenacawh (Powhatan), skillfully resisted English encroachment in Virginia. While often portrayed through the lens of Pocahontas, the Powhatan people engaged in a series of conflicts (the Anglo-Powhatan Wars) that demonstrated their strategic understanding of the terrain and their ability to inflict significant losses on the colonizers. They initially sought to absorb the English into their tribute system, but when that failed, they used hit-and-run tactics and ambushes to defend their territory.

Further north, the Wampanoag sachem Metacom, known to the English as King Philip, ignited "King Philip’s War" (1675-1678), a brutal conflict that engulfed much of New England. Metacom forged a broad alliance of tribes, including the Narragansett, Nipmuc, and Pocumtuc, to push back against English expansion. Their tactics, which included coordinated raids on colonial settlements and the adoption of some English fighting methods, initially devastated the colonial frontier. Though ultimately defeated, the war stands as a testament to the Native capacity for strategic organization and fierce defense, inflicting the highest per capita casualties on English colonists of any war in American history.

Even more successful, at least temporarily, was the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 in what is now New Mexico. Led by Popé, a Tewa religious leader, the Pueblo people united across distinct linguistic and cultural groups to launch a coordinated uprising against Spanish colonial rule, which had been marked by forced labor, religious persecution, and cultural suppression. The revolt was meticulously planned and executed, driving the Spanish entirely out of New Mexico for twelve years. This unprecedented success demonstrated the power of unity and a shared desire for cultural and spiritual autonomy. It forced the Spanish to adopt a more conciliatory approach upon their return, recognizing certain Pueblo rights and religious freedoms.

The Wampum Belt and the Diplomatic Dance: Alliances and Negotiation

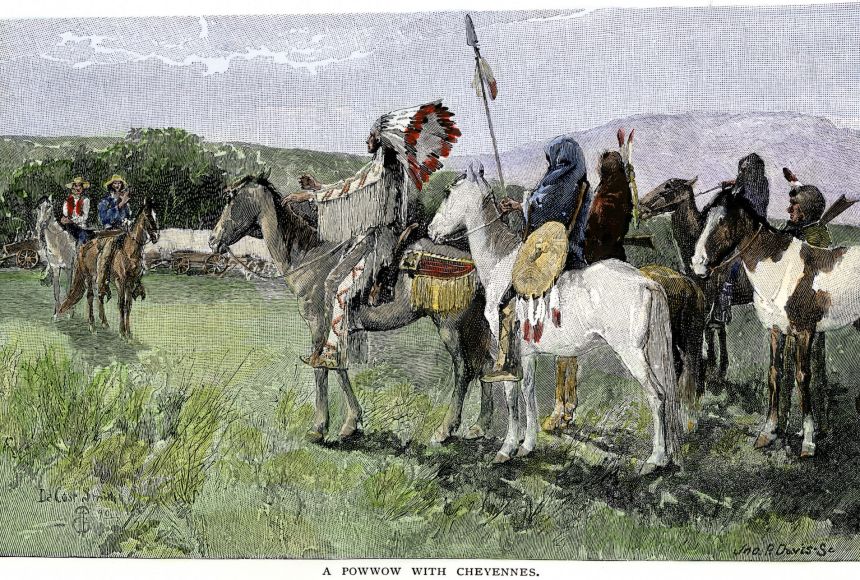

While military might was crucial, Native nations also understood the power of diplomacy and strategic alliances. They often leveraged the rivalries between European powers – the English, French, and Spanish – playing one against the other to secure advantages, protect territory, or gain access to desired goods.

The Iroquois Confederacy (Haudenosaunee) stands as a prime example of diplomatic genius. Situated strategically between French Canada and the English colonies, the Haudenosaunee mastered the art of "playing the balance of power." They forged the "Covenant Chain" alliance with the English in the late 17th century, a complex series of agreements that recognized their mutual interests and solidified the Iroquois’ position as a dominant force in the Great Lakes region. The Haudenosaunee’s internal political structure, based on the Great Law of Peace, provided a stable foundation for their external relations, allowing them to project significant power and influence over other Native nations and European colonial governments alike. As historian Francis Jennings noted, the Iroquois "became a significant geopolitical force, not merely a tribal entity."

Treaties, though often misunderstood and later violated by Europeans, were also a key element of Native diplomatic strategy. From the Native perspective, treaties were sacred agreements, often accompanied by elaborate ceremonies and the exchange of wampum belts, which served as living documents of the commitments made. These agreements were intended to define boundaries, establish trade relations, and ensure peaceful coexistence. While Europeans often viewed treaties as a means to acquire land, Native leaders saw them as agreements for shared use or coexistence, reflecting different understandings of land ownership and sovereignty.

The Axe and the Plow: Cultural and Technological Adaptation

Survival also necessitated pragmatic adaptation. Native Americans were not static societies; they readily adopted new technologies and sometimes even aspects of European culture when it served their interests, without necessarily abandoning their core identities.

The adoption of European firearms, particularly muskets and rifles, revolutionized Native warfare. Nations quickly learned to use, maintain, and even repair these weapons, integrating them into their existing fighting styles. Similarly, metal tools like axes, knives, and kettles were prized for their durability and efficiency, often replacing traditional stone, bone, and wood implements. Horses, introduced by the Spanish, transformed the lives of Plains tribes, leading to the development of a highly mobile and powerful equestrian culture.

The fur trade, while ultimately having devastating consequences by creating economic dependencies and encouraging overhunting, was initially a Native-driven enterprise. Indigenous hunters and trappers supplied European markets with beaver pelts and other furs, receiving European manufactured goods in return. This trade fostered new economic relationships and sometimes allowed Native groups to acquire resources that strengthened their positions against rivals or encroaching colonists.

Cultural adaptation also extended to language and legal systems. Many Native leaders learned European languages to facilitate negotiations, and some groups even attempted to use colonial legal systems to defend their land rights, though often with limited success. This selective adoption was a strategic choice, a means to engage with the invaders on their own terms where necessary, without sacrificing cultural integrity.

The Drum and the Vision: Cultural Preservation and Spiritual Resilience

Amidst the onslaught, maintaining cultural identity and spiritual traditions was paramount. Native communities actively resisted cultural assimilation, understanding that their spiritual beliefs, languages, and social structures were the bedrock of their existence.

Oral traditions, ceremonies, and storytelling became vital conduits for transmitting knowledge, history, and values across generations. Elders played a crucial role in ensuring that sacred narratives, traditional ecological knowledge, and moral precepts endured. Languages, too, were fiercely guarded, serving as powerful markers of identity and community.

In times of extreme crisis, spiritual revitalization movements emerged, offering a powerful form of resistance. The Delaware Prophet Neolin, in the mid-18th century, preached a message of rejecting European goods and returning to traditional ways, inspiring Pontiac’s Rebellion against British rule. Similarly, Handsome Lake, a Seneca prophet, experienced a series of visions in the late 18th and early 19th centuries that led to the formation of the Longhouse Religion (Gaiwiio). This faith synthesized traditional Seneca beliefs with elements of Christian morality, advocating for peace, temperance, and the preservation of Iroquois culture, offering a path for spiritual and social renewal amidst profound societal disruption.

The Westward Path and the Consolidated Nation: Migration and Consolidation

As colonial pressure mounted, some Native groups chose to migrate, moving westward to escape the encroaching frontier. This was often a painful decision, involving leaving ancestral lands, but it offered a chance for renewed autonomy. For example, many eastern tribes, like elements of the Shawnee and Delaware, moved into the Ohio Valley and beyond, attempting to reestablish their communities away from direct colonial control.

Another strategy was the consolidation of fragmented groups. As populations dwindled due to disease and warfare, remnants of different tribes sometimes merged, forming new confederacies or strengthening existing ones. The Creek Confederacy in the Southeast, for instance, grew into a powerful political and military entity by incorporating diverse linguistic and cultural groups under a common structure, allowing them to present a united front against European expansion.

Enduring Legacy

The Native American experience during the colonial era was one of relentless challenge, profound loss, but also extraordinary resilience. Their strategies for survival – whether through armed resistance, sophisticated diplomacy, pragmatic adaptation, or steadfast cultural preservation – were not always successful in preventing land loss or demographic decline. Yet, they ensured that Indigenous cultures, languages, and identities persisted.

The legacy of these strategies is evident today in the vibrant Native nations across the continent, sovereign entities that have overcome centuries of adversity. Their struggles for survival in the colonial era laid the groundwork for ongoing fights for self-determination, treaty rights, and cultural revitalization. The history of Native American survival is a testament to the unconquered spirit, a powerful narrative of ingenuity and perseverance in the face of existential threat, reminding us that true strength often lies not in conquest, but in the enduring will to exist.