The Unending Echo of Wounded Knee: Leonard Peltier’s Half-Century Quest for Justice

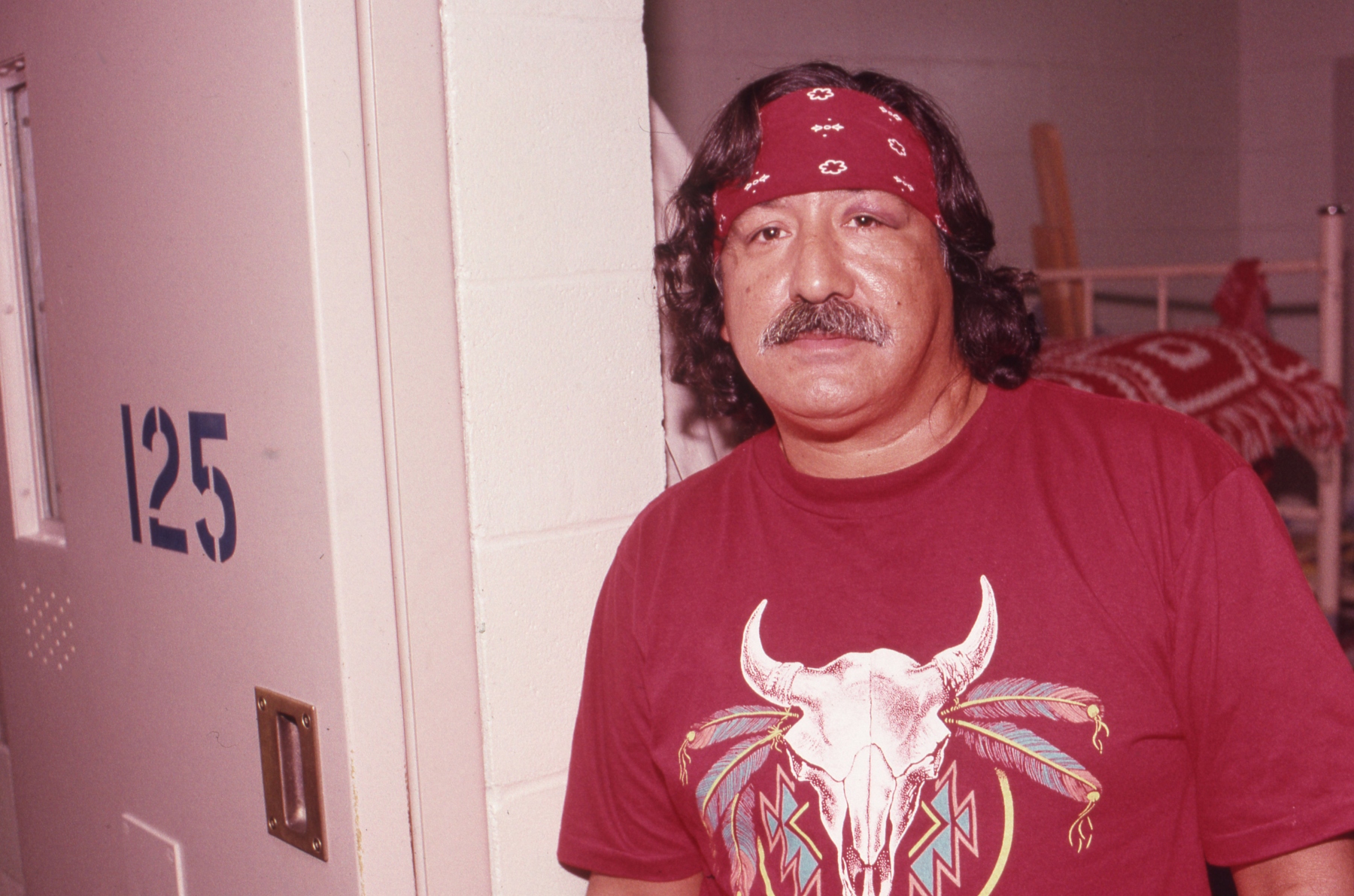

In the annals of American justice, few cases ignite such fervent debate and passionate advocacy as that of Leonard Peltier. For nearly half a century, the name Leonard Peltier has been synonymous with the ongoing struggle for Indigenous rights, the complexities of federal jurisdiction on tribal lands, and the enduring question of what constitutes true justice. Imprisoned since 1976 for the murder of two FBI agents during a 1975 shootout on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, Peltier, now 79 years old and in declining health, remains a symbol for many of a system that has historically failed Native Americans. His story is not merely a legal saga; it is a historical overview of a tumultuous era, a testament to resilience, and a poignant reminder of unresolved grievances.

The roots of the Peltier case are deeply embedded in the turbulent landscape of the early 1970s, a period marked by the rise of the American Indian Movement (AIM) and escalating tensions between federal authorities and Native American activists. AIM, founded in 1968, emerged as a militant voice for Indigenous self-determination, sovereignty, and the redress of historical injustices. Their activism often involved direct confrontations, most notably the 1972 occupation of the Bureau of Indian Affairs building in Washington D.C., and the dramatic 1973 Wounded Knee standoff on Pine Ridge, a 71-day siege that brought national and international attention to the plight of Native Americans.

Pine Ridge itself was a powder keg. The reservation was plagued by internal strife, fueled by poverty, political corruption, and a proxy war between AIM supporters and the tribal government, led by Chairman Dick Wilson. Wilson’s private militia, known as the "Guardians of the Oglala Nation" (GOONs), was frequently accused of violence against AIM members and their sympathizers, often with tacit support from federal agencies. Between 1973 and 1975, over 60 Native Americans died violently on Pine Ridge, a period often referred to as the "Reign of Terror." AIM members, including Peltier, were invited to the reservation by traditional elders to provide security and protection against the GOONs and the perceived indifference of law enforcement.

It was into this volatile environment that June 26, 1975, exploded. Two FBI agents, Jack Coler and Ronald Williams, entered the Jumping Bull property on Pine Ridge in unmarked vehicles, reportedly searching for a young man accused of stealing a pair of cowboy boots. What ensued was a chaotic and intense firefight involving dozens of individuals. When the smoke cleared, Coler and Williams were dead, both shot execution-style at close range after being wounded. Joe Stuntz Killsright, an AIM member, was also killed. The precise sequence of events leading to the deaths of the agents remains disputed, but the federal government quickly launched one of the largest manhunts in FBI history.

Peltier and three other AIM members – Bob Robideau, Darrelle Butler, and Dino Butler – were indicted for the agents’ murders. Robideau and Butler were tried first in Cedar Rapids, Iowa. Crucially, their defense successfully argued self-defense, portraying the shootout as an ambush initiated by the FBI, and they were acquitted. Peltier, however, was tried separately in Fargo, North Dakota, a decision his supporters argue was a deliberate attempt by the prosecution to secure a conviction in a more conservative jurisdiction.

Peltier’s trial was fraught with controversy. The prosecution’s case against him hinged largely on the testimony of Myrtle Poor Bear, an Oglala Sioux woman who initially provided affidavits stating she was Peltier’s girlfriend and had witnessed him shoot the agents. However, Poor Bear later recanted her testimony, claiming she had been coerced and threatened by FBI agents into signing the affidavits. Despite her recantation, the court allowed the affidavits to be used for the purpose of extraditing Peltier from Canada, where he had fled. During the trial itself, Poor Bear was deemed unreliable and was not allowed to testify for the prosecution.

Another critical piece of evidence involved ballistics. The prosecution alleged that a specific .223 shell casing found near Agent Coler’s body matched a weapon attributed to Peltier. However, a crucial FBI ballistics report, which stated that the casing could not be definitively linked to Peltier’s gun, was withheld from the defense until years after the trial. This suppressed evidence, combined with the coerced testimony of Myrtle Poor Bear, forms the bedrock of arguments for Peltier’s wrongful conviction. In 1977, Leonard Peltier was convicted of two counts of first-degree murder and sentenced to two consecutive life terms.

The aftermath of Peltier’s conviction has been a relentless legal and political struggle. His appeals have consistently been denied, even as significant questions about the fairness of his trial have mounted. In 1991, the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals acknowledged that the FBI had "misleadingly" presented evidence during the extradition process and conceded that "there is some evidence that the FBI was not without fault in the June 26, 1975, firefight." Yet, the court upheld Peltier’s conviction, stating that "it is enough that the jury was presented with sufficient evidence to convict."

Perhaps the most damning judicial commentary came from Judge Gerald W. Heaney of the Eighth Circuit, who, in a dissenting opinion in 1991, stated: "The government’s case against Peltier was a weak one… A good deal of the evidence presented by the government was suspect… We cannot ignore the very real possibility that a grave injustice has been done." Judge Heaney later reiterated this sentiment, advocating for executive clemency.

The campaign for Peltier’s freedom has gained international recognition, transforming him into a cause célèbre for human rights organizations, Indigenous rights advocates, and numerous public figures. Amnesty International considers him a political prisoner who was unfairly tried and convicted, and has repeatedly called for his release. Desmond Tutu, Nelson Mandela, the Dalai Lama, Pope Francis, and countless celebrities, artists, and politicians have publicly supported clemency for Peltier. Their arguments are multifaceted: the documented prosecutorial misconduct, the withheld exculpatory evidence, the coerced testimony, the disproportionate sentence compared to his co-defendants who were acquitted, and Peltier’s deteriorating health and advanced age.

Opponents of clemency, primarily the FBI and the families of agents Coler and Williams, maintain that Peltier is a convicted murderer who received a fair trial and should serve his full sentence. They emphasize the brutality of the agents’ deaths and view any attempt to release Peltier as a betrayal of law enforcement and a denial of justice for the victims. The FBI has consistently and vehemently opposed any form of clemency, arguing that Peltier is unrepentant and that his release would set a dangerous precedent.

Over the decades, Peltier’s hopes for release have hinged on parole hearings and presidential clemency. He has been denied parole multiple times, with the parole board consistently citing the severity of the offense. His best chance for clemency came at the end of President Bill Clinton’s term in 2001, when a large rally was held outside the White House, but Clinton ultimately denied the request. Similar hopes were raised during the Obama administration, but President Obama, too, declined to grant clemency.

As President Joe Biden’s term progresses, the pressure for clemency for Peltier has intensified. With his health failing – Peltier suffers from diabetes, hypertension, and a heart condition – advocates argue that his continued incarceration is a moral stain on the American justice system. His supporters contend that, regardless of the original charges, the documented flaws in his trial, the passage of time, and his current condition warrant compassionate release. They point to the fact that he has spent 48 years behind bars, a term that far exceeds sentences for many violent crimes.

Leonard Peltier’s case is more than a legal battle; it is a lens through which to examine the complex and often painful history of Indigenous-federal relations in the United States. It speaks to the legacy of colonialism, the fight for self-determination, and the enduring quest for a justice system that is truly equitable for all. Whether one believes he is a cold-blooded murderer or a political prisoner, the Leonard Peltier case stands as a powerful testament to the unresolved tensions of a bygone era, echoing the unanswered questions of Wounded Knee and demanding a re-examination of justice, half a century later. His continued incarceration forces the nation to confront its past and consider what true reconciliation might look like in the present. The debate rages on, and until a resolution is found, Leonard Peltier remains a living embodiment of America’s unfinished business.