The Grand Illusion: How Colonial Powers Fabricated Legitimacy for Global Domination

The age of empire, a period stretching from the 15th to the mid-20th century, saw European powers carve up vast swathes of the globe, claiming sovereignty over lands and peoples far beyond their shores. This monumental appropriation of territory, resources, and human lives was not, however, a simple act of brute force. To legitimize their actions in the eyes of their own populations, international rivals, and sometimes even the colonized, imperial powers constructed an elaborate, often contradictory, web of justifications. These rationalizations, cloaked in legal, moral, religious, and scientific language, served to transform audacious acts of conquest into seemingly defensible enterprises, masking the underlying drive for wealth, power, and strategic advantage.

At the heart of many early colonial claims lay the Divine Right and Religious Imperative. European monarchs, often believing their rule was divinely sanctioned, saw the expansion of their empires as an extension of God’s will. The Pope, as God’s representative on Earth, played a crucial role in legitimizing these early endeavors. Papal Bulls like Inter Caetera (1493) and Romanus Pontifex (1455) granted Portugal and Spain the right to "discover, conquer, and subjugate" non-Christian lands, explicitly linking territorial acquisition with the spread of Christianity. This framework allowed for the forced conversion of indigenous populations and the destruction of their spiritual practices, framing it as a humanitarian act of salvation rather than cultural annihilation. The idea was simple: if God willed it, who were mere mortals to object? This religious zeal provided a powerful moral shield, allowing conquistadors and explorers to commit atrocities under the banner of faith.

As the Enlightenment dawned and religious justifications waned in secular importance, a new, equally pervasive rationale emerged: the "Civilizing Mission". This concept posited that European nations, with their advanced technology, governance, and culture, had a moral obligation to uplift and "civilize" the "savage" or "backward" peoples of the world. This often meant imposing European languages, legal systems, education, and economic practices, all while dismissing indigenous knowledge and societal structures as primitive. Rudyard Kipling’s 1899 poem, "The White Man’s Burden," famously encapsulated this sentiment, urging Americans to "Take up the White Man’s burden— / Send forth the best ye breed— / Go bind your sons to exile / To serve your captives’ need." This was not merely a poetic flourish; it was a deeply ingrained belief that permeated colonial policy. Lord Macaulay’s 1835 "Minute on Indian Education," for instance, argued for creating a class of Indians "Indian in blood and colour, but English in taste, in opinions, in morals, and in intellect," thereby justifying the imposition of English education and cultural norms. This narrative conveniently ignored the rich and complex civilizations that existed in places like India, China, and across Africa, portraying them as blank slates awaiting European enlightenment.

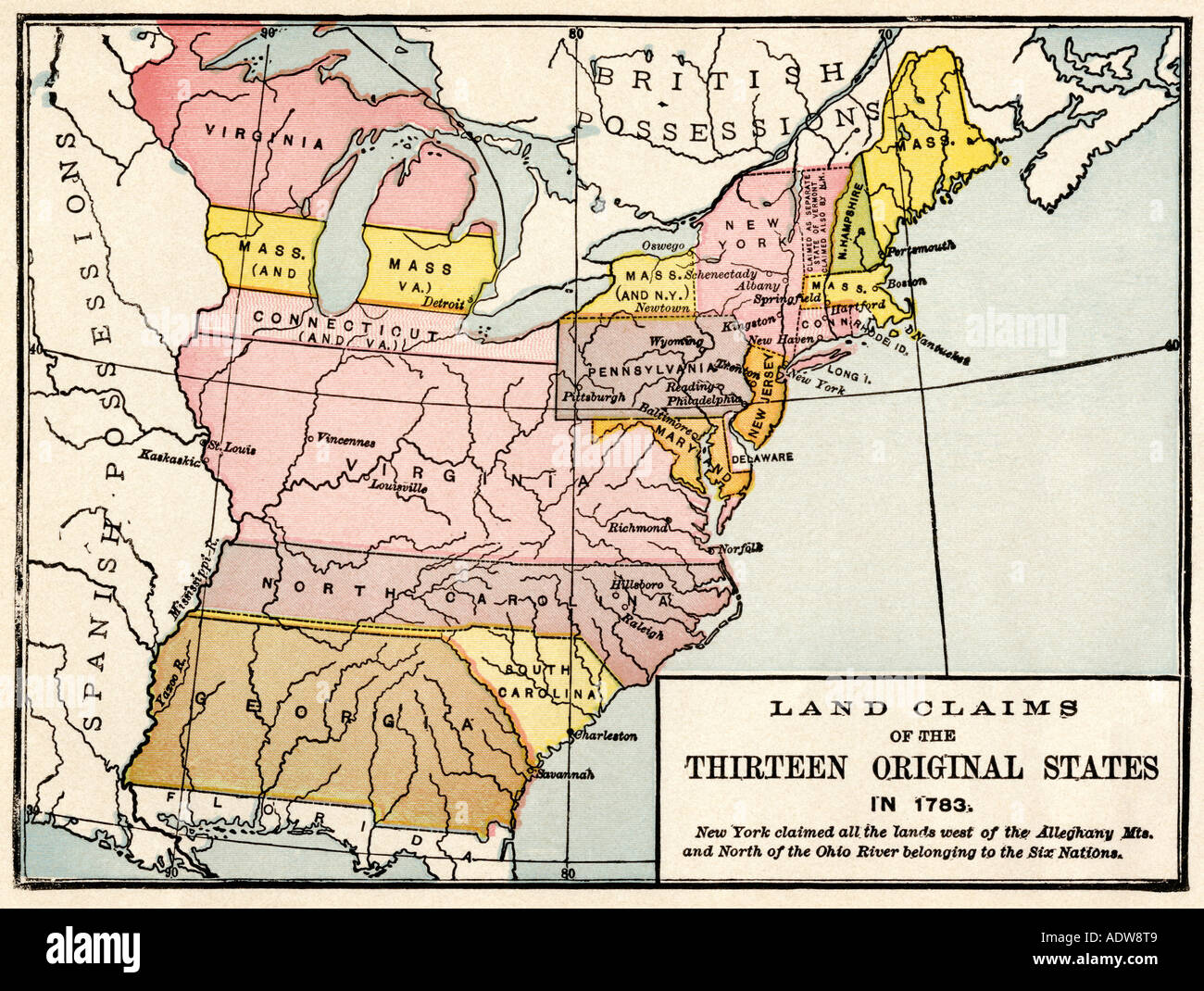

Complementing the civilizing mission were legal fictions and the Doctrine of Discovery. One of the most insidious of these was the concept of Terra Nullius, Latin for "land belonging to no one." This doctrine was applied to lands that, despite being inhabited, were deemed by Europeans to be "empty" or "unoccupied" because they lacked European-style agriculture, permanent settlements, or recognizable forms of governance. Indigenous peoples, living in harmony with their environment through nomadic or semi-nomadic lifestyles, or with communal land ownership systems, were often seen as not "using" the land in a way Europeans understood or valued. Australia, for example, was initially declared terra nullius by the British, a legal premise that was only overturned in 1992 by the landmark Mabo v. Queensland High Court decision, which recognized indigenous native title.

The Doctrine of Discovery, another cornerstone of colonial legal justification, asserted that the first European power to "discover" and claim new territory gained title to it, even if indigenous peoples already resided there. This doctrine, rooted in the aforementioned Papal Bulls, became enshrined in international law and was later adopted by emerging nations like the United States. In the 1823 US Supreme Court case Johnson v. M’Intosh, Chief Justice John Marshall invoked the Doctrine of Discovery to declare that Native Americans had a mere "right of occupancy" to their lands, while European discoverers acquired ultimate title. This legal framework effectively stripped indigenous nations of their sovereign rights, providing a powerful legal cover for land seizures across continents.

Beyond these moral and legal justifications lay the undeniable driver of Economic Imperatives. The Industrial Revolution in Europe created an insatiable demand for raw materials—cotton, rubber, timber, minerals, spices—and new markets for manufactured goods. Colonies became vast resource reservoirs and captive markets. The pursuit of wealth, though often presented as a secondary benefit, was frequently the primary motivation for expansion. The British East India Company, for instance, transformed from a trading enterprise into a de facto ruling power in India, driven by the immense profits to be made from spices, textiles, and later, opium. King Leopold II’s brutal exploitation of the Congo Free State for rubber and ivory stands as a horrific testament to the extreme lengths to which economic greed could drive colonial policies, leading to the deaths of millions of Africans.

Finally, Geopolitical Strategy and National Prestige played a significant role. The scramble for Africa in the late 19th century, culminating in the Berlin Conference of 1884-85, saw European powers race to claim African territories, not just for resources, but to prevent rival nations from gaining an advantage. Possessing a vast empire became a symbol of national strength, a measure of a nation’s standing on the global stage. Empires provided strategic naval bases, coaling stations, and manpower for armies, bolstering a nation’s military and political influence. Even if a territory offered little immediate economic benefit, its strategic location or potential future value could be enough to justify its acquisition. The Suez Canal, for example, was a critical strategic asset that linked the British Empire’s holdings in the East with its European heartland, cementing Britain’s control over Egypt.

It is also crucial to acknowledge the role of coerced consent and manipulated treaties. Colonial powers often presented their land claims as legitimate through "agreements" signed with indigenous leaders. However, these treaties were frequently signed under duress, based on severe power imbalances, or fundamentally misunderstood due to linguistic and cultural differences. Indigenous concepts of land ownership, often communal and rooted in stewardship rather than exclusive possession, clashed irreconcilably with European notions of individual property rights and sovereignty. The Treaty of Waitangi (1840) in New Zealand, for instance, remains a contentious document, with significant discrepancies between the English and Māori versions regarding sovereignty and land rights, leading to generations of disputes.

In retrospect, the justifications for colonial land claims reveal themselves as a carefully constructed edifice of self-serving rationalizations. From divine mandate to civilizing mission, from legal fictions to economic necessity, these arguments provided a moral and legal veneer for what was, at its core, a massive undertaking of power projection, resource extraction, and cultural subjugation. While the era of formal colonialism has largely ended, the legacies of these justifications – in international law, national borders, economic disparities, and ongoing struggles for indigenous rights – continue to resonate, reminding us of the enduring impact of a grand illusion built on conquest.