The Forgotten Uprising: Guale’s Fierce Defiance in Spanish Florida

By

Introduction: Blood on the Barrier Islands

In the humid autumn of 1597, a fragile peace shattered across the barrier islands of what is now coastal Georgia. For decades, the indigenous Guale people had endured the encroaching dominion of Spanish Florida, a precarious colonial outpost striving to extend its reach and its faith. But on a fateful September morning, the simmering resentment boiled over into open rebellion, marking one of the most significant and often overlooked acts of indigenous resistance in early North American history. This was not a mere skirmish but a calculated uprising, a desperate attempt by a proud people to reclaim their land, their culture, and their very souls from the relentless grip of European conquest. The Guale Rebellion, though ultimately suppressed, stands as a potent testament to the enduring human spirit in the face of overwhelming odds.

The Precarious Foothold: Spanish Florida and the Guale Nation

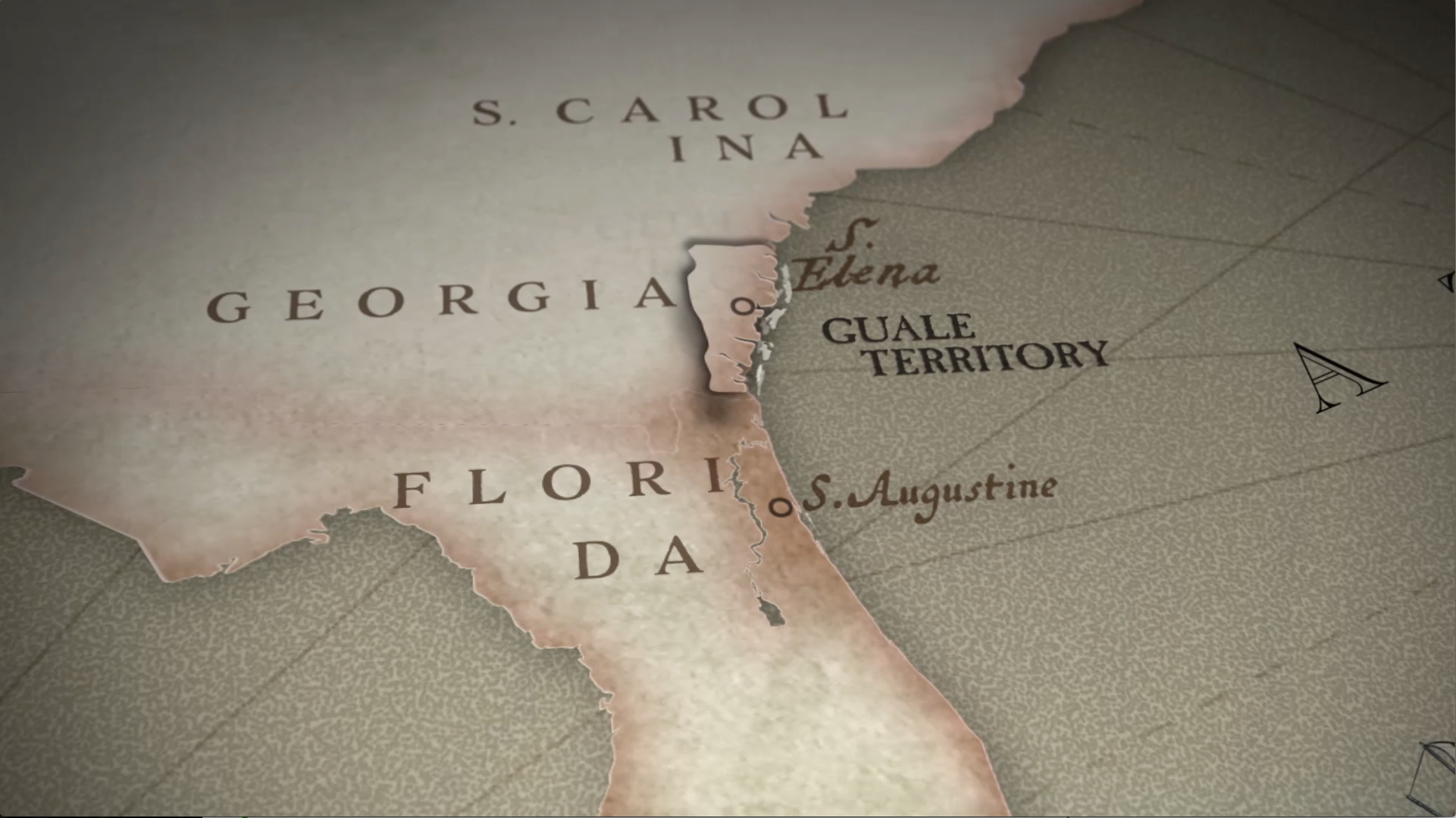

To understand the rebellion, one must first grasp the context of Spanish Florida in the late 16th century. St. Augustine, founded in 1565, was less a thriving colony and more a military and missionary outpost, constantly struggling for resources and battling hostile indigenous tribes and European rivals. Its primary strategic value lay in protecting the Spanish treasure fleets sailing the Gulf Stream. Beyond St. Augustine, the Spanish sought to pacify and convert the native populations, establishing a network of missions, or doctrinas, that stretched northward along the coast into the territory of the Guale.

The Guale people, a Muskhogean-speaking group, inhabited a series of fertile barrier islands and the adjacent mainland, roughly from the Altamaha River north to the Savannah River. They were a complex, stratified society with powerful chiefs (known as micos), a sophisticated agricultural system (maize, beans, squash), and a rich ceremonial life. Their towns, often situated near estuaries and rivers, were centers of trade and political influence. When the Spanish arrived, the Guale initially engaged in wary diplomacy, recognizing the power of the newcomers but also fiercely guarding their autonomy.

The Franciscan friars, eager to win souls for God and Crown, were the spearhead of this spiritual conquest. By 1597, several missions had been established in Guale territory, including those on St. Catherines Island (Santa Catalina), Sapelo Island (San José), and Jekyll Island (San Buenaventura). These missions, however, were not simply places of worship. They were instruments of cultural transformation, aiming to reducir (reduce) the scattered Guale populations into more manageable, sedentary communities, often disrupting traditional settlement patterns and social structures.

"The Spanish saw the Guale as potential converts and laborers," notes historian J. Michael Francis, "but the Guale viewed them as intruders, bringing disease, demanding tribute, and attempting to dismantle their ancient way of life." The introduction of European diseases, to which the Guale had no immunity, decimated their populations, further fueling resentment. The Spanish also imposed a system of forced labor (repartimiento) for colonial projects and demanded food tributes, placing an unbearable burden on the Guale economy. Traditional Guale spiritual practices were condemned as paganism, and their social customs, such as polygyny, were outlawed.

The Spark: A Chief’s Humiliation and a Friar’s Condemnation

The immediate catalyst for the rebellion was a potent mix of personal humiliation, cultural clash, and the heavy hand of missionary zeal. The Guale chiefdom was a hereditary system, and a young man named Juanillo was heir apparent to the mico of Tolomato (likely on what is now St. Catherines Island). However, Juanillo had allegedly taken a second wife, a practice strictly forbidden by the Franciscan missionaries, particularly by Fray Pedro de Corpa, the resident friar at Tolomato.

Fray Corpa, known for his unyielding adherence to Christian doctrine, publicly denounced Juanillo, not only for his polygyny but also for his perceived defiance of Spanish authority. He declared Juanillo unfit to rule, effectively disinheriting him and undermining his status within Guale society. This act, meant to assert Christian morality and Spanish control, was a profound affront to Guale customs and a direct challenge to the authority of their leaders. It was a bridge too far.

In the Guale worldview, the spiritual and temporal realms were intertwined, and the mico held immense power, both political and sacred. For a foreign priest to usurp this authority, to dictate succession, was an intolerable insult. Juanillo, feeling his honor and future imperiled, gathered his kinsmen and allies. He argued that the Spanish friars were destroying their traditions, imposing alien laws, and threatening their very existence. He rallied the Guale by declaring, "They will prevent us from being men."

The Uprising Unfolds: A Coordinated Strike

On the dawn of September 14, 1597, the simmering rage exploded into violence. Juanillo and his followers attacked the mission at Tolomato. Fray Pedro de Corpa was the first martyr. He was dragged from his church and killed, his body left to desecrate, a clear message of rejection.

The rebellion spread with terrifying speed and coordination. Juanillo’s message resonated deeply with other Guale communities who shared similar grievances. Within days, the revolt encompassed a vast stretch of the Guale coast.

- Tolomato: Fray Pedro de Corpa killed (September 14).

- Tupiqui: Fray Blas Rodríguez, a beloved friar, was killed shortly after Corpa. His death was particularly shocking as he was known for his gentleness.

- Asao (St. Simon’s Island): Fray Miguel de Añon and Fray Antonio de Badajoz were killed.

- Jekyll Island (San Buenaventura): Fray Francisco de Berascola, despite being warned, chose to stay and was killed.

A total of five Franciscan friars were martyred in the initial wave of attacks. Only Fray Francisco de Avila, stationed at Asao, and Fray Pedro de Chozas, at a more remote mission, managed to escape the immediate slaughter, though Avila was captured and held for ransom. The Guale burned churches, destroyed mission buildings, and sought to erase all physical traces of Spanish presence and Christian influence. Their aim was not merely to kill the friars but to purge their land of the foreign ideology they represented.

The Guale also attempted to draw other tribes, particularly the Timucua to the south, into the rebellion. While some Timucua initially showed sympathy, the Spanish managed to prevent a wider conflagration through a mix of diplomacy and intimidation.

Spanish Retribution: The Scorch and the Sword

News of the massacre reached St. Augustine, sending shockwaves through the small colonial community. Governor Gonzalo Méndez de Canzo, a veteran soldier and experienced administrator, immediately recognized the gravity of the situation. He understood that if the Guale rebellion went unpunished, it would inspire other tribes and imperil the entire Spanish Florida enterprise.

Méndez de Canzo launched a series of punitive expeditions, personally leading some of the forces. The Spanish response was brutal and uncompromising. Utilizing their superior weaponry – arquebuses, swords, and armor – they systematically targeted Guale towns, burning homes, destroying crops, and seizing food stores. This "scorched earth" policy was designed to starve the Guale into submission and break their will to resist.

The marshy, island-strewn terrain, however, made it difficult for the Spanish to engage the elusive Guale warriors in decisive battles. The Guale, masters of their environment, used the dense woods and waterways to their advantage, fading into the landscape when confronted. Méndez de Canzo pursued Juanillo relentlessly, but the Guale leader proved difficult to capture.

The pursuit and suppression of the rebellion stretched for months, draining the meager resources of St. Augustine. Eventually, in 1601, a combined force of Spanish soldiers and allied Timucuan warriors cornered Juanillo and his remaining followers. Juanillo was killed, and his head, along with those of several other rebel leaders, was brought back to St. Augustine as a grim trophy, a stark warning to any who dared defy the Crown.

Aftermath and Legacy: A People Displaced, A Policy Shifted

The Guale Rebellion left an indelible mark on both the indigenous people and the Spanish colonial strategy. For the Guale, the consequences were devastating. Their populations, already weakened by disease, were further decimated by the Spanish retaliation and subsequent famine. Many were forced to abandon their ancestral lands, seeking refuge with other tribes or relocating closer to Spanish control. The political structure of the Guale was shattered, and their ability to resist as a unified force was severely diminished. Over the next century, the Guale would face continued pressure from encroaching English colonists from the north and raids from other indigenous groups, eventually leading to their effective disappearance as a distinct cultural entity, merging with other groups like the Yamasee.

For the Spanish, the rebellion forced a reassessment of their missionary strategy. While they did not abandon their efforts, they adopted a more cautious approach. The missions were re-established, but often with a stronger military presence and a greater emphasis on diplomacy alongside evangelism. The Guale territory remained a contested frontier, a buffer zone between Spanish Florida and the burgeoning English colonies to the north. The rebellion underscored the limits of Spanish power and the fierce determination of indigenous peoples to protect their heritage.

The Guale Rebellion of 1597 is more than just a footnote in colonial history. It is a powerful narrative of resistance, a testament to the fact that even in the face of overwhelming technological and military might, indigenous peoples fought valiantly to preserve their way of life. It reminds us of the profound human cost of colonialism and the complex, often violent, interactions that shaped the early Americas. Today, archaeological efforts continue to uncover the remains of Guale towns and Spanish missions, providing tangible links to this pivotal moment and allowing the whispers of defiance from those barrier islands to echo across the centuries. The Guale may have been vanquished, but their spirit of resistance, born in the blood-soaked autumn of 1597, remains an enduring part of the American story.