Mirrors and Myths: Early European Art’s Reflection of Native Americans

The moment Christopher Columbus’s ships sighted land in 1492 marked not only a seismic shift in global history but also the genesis of a complex and often contradictory visual narrative. For Europeans, the "New World" was an unprecedented canvas, and its indigenous inhabitants, a subject ripe for interpretation, projection, and ultimately, misrepresentation. Early European art depicting Native Americans was less a faithful portrait and more a mirror reflecting Europe’s own evolving anxieties, desires, and justifications for conquest. From idealized "noble savages" to monstrous cannibals, these images profoundly shaped European perceptions and, tragically, laid groundwork for centuries of colonial policy.

Before any direct observation, the very concept of the "Other" beyond the known world had deep roots in European imagination. Medieval cartography and travelogues were replete with monstrous races – dog-headed men, cyclops, and creatures with mouths in their chests. While Native Americans were not depicted as such, this existing framework for the exotic and the unknown certainly colored initial expectations. Columbus himself, in his first letters back to Spain, provided the initial, foundational descriptions. He spoke of people "naked as their mothers bore them," "very well made, with very handsome bodies," and "so naive and so free with their possessions that no one who has not witnessed them would believe it." He noted their lack of iron, their generosity, and their apparent lack of a complex religion, concluding they would be "easy to convert and civilize."

These early written accounts, often filtered through the lens of European classical ideals, quickly found their way into visual representation. The first widely circulated images of Native Americans were not direct observations but rather allegorical figures, personifying the newly discovered continent of America. Typically, America was depicted as a bare-breasted woman, adorned with feathers, often holding a bow and arrow, and sometimes accompanied by exotic animals like parrots or armadillos. A famous example is Jan van der Straet’s (Stradanus) engraving America (c. 1589), which shows Amerigo Vespucci, clothed and holding a banner, "discovering" a naked, reclining America who awakens from a hammock. This image powerfully encapsulates the European gaze: a virile, civilized European encountering a passive, uncultured, yet alluring, land and people.

This allegorical representation soon branched into two dominant and often conflicting tropes: the "Noble Savage" and the "Brutal Savage." The "Noble Savage" emerged from the idealization of a people living in a supposedly natural, uncorrupted state, free from the perceived vices and complexities of European civilization. Amerigo Vespucci’s Mundus Novus (1503), a widely read account, detailed a people who lived communally, without private property, and in a state of primal innocence. He wrote, "They have no property… they live together without a king, without dominion, and each is his own master." This notion resonated with European philosophical currents, particularly during the Enlightenment, finding its most famous articulation in Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s concept of humanity’s natural goodness corrupted by society.

Artistic representations of the "Noble Savage" often emphasized physical perfection, a connection to nature, and an untroubled existence. They were frequently depicted with strong, classical musculature, their nakedness signifying not shame but purity and freedom. However, even this "noble" depiction was a projection, stripping Native Americans of their complex societies, spiritual beliefs, and individual identities, reducing them to a romanticized ideal that served as a critique of European decadence rather than an accurate portrayal.

Simultaneously, the "Brutal Savage" narrative gained traction, often fueled by sensationalized accounts of cannibalism and warfare. While some indigenous groups did practice ritualistic anthropophagy, particularly among certain Carib tribes, these practices were exaggerated and generalized across all Native American peoples. This narrative served a crucial purpose for European colonial powers: it justified conquest, enslavement, and the imposition of European "civilization" and Christianity. If Native Americans were inherently barbaric, then European intervention, no matter how violent, could be framed as a benevolent act.

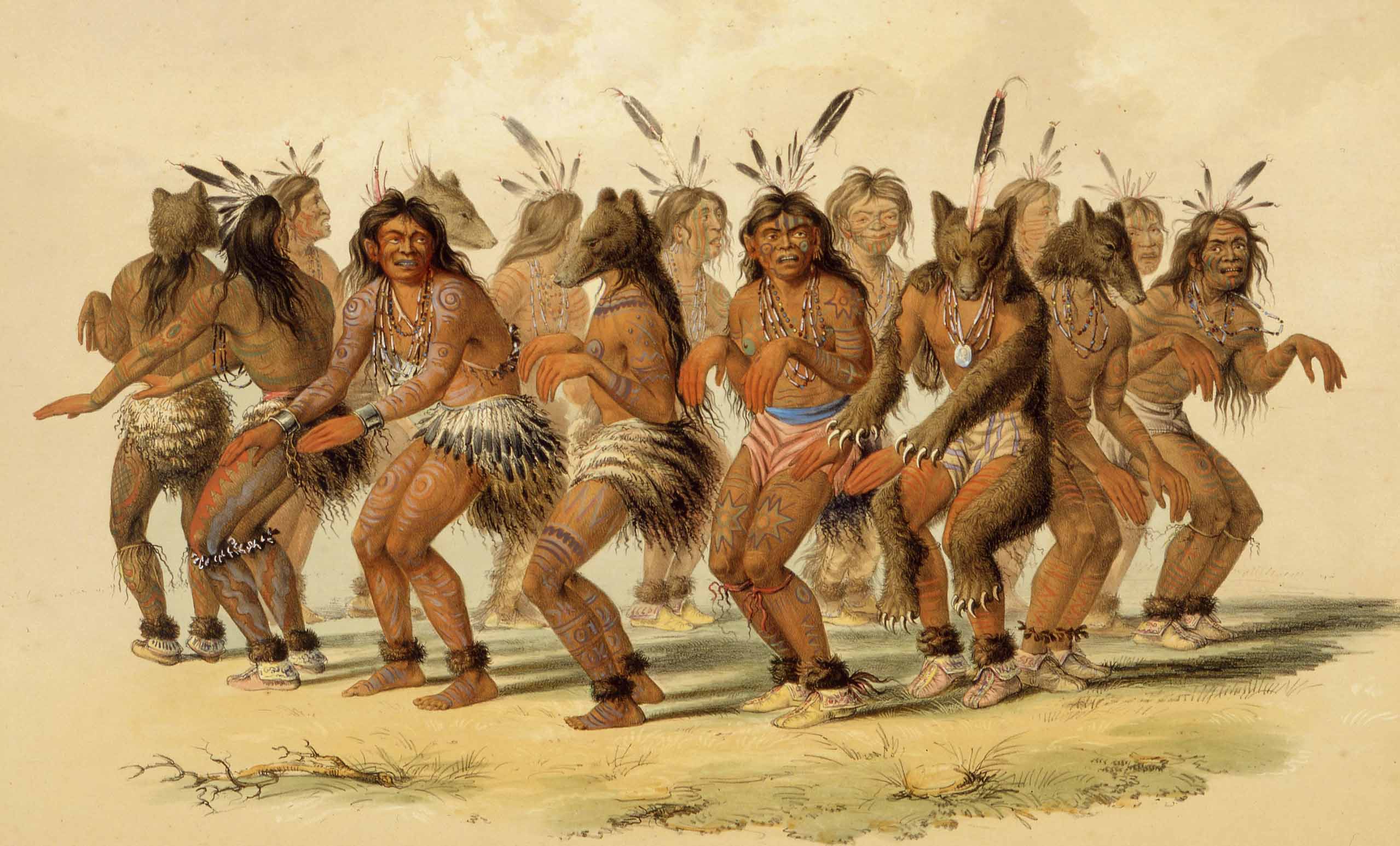

Theodor de Bry’s immensely influential series of engravings, Grand Voyages (1590-1634), stands as a pivotal example of how these narratives were visually disseminated and solidified. De Bry, a German engraver, never visited the Americas. His work was based on various published accounts, most notably John White’s watercolors from the Roanoke colony in the late 16th century. White, who spent time among the Carolina Algonquians, produced some of the most accurate and sensitive early depictions of Native American life, showing villages, ceremonies, and individuals with a degree of ethnographic detail.

However, when De Bry re-engraved White’s images for publication, he often took significant liberties. He "Europeanized" the Native Americans’ physiques, giving them classical Greek and Roman musculature, and altered their facial features to align with European aesthetic ideals. More importantly, he introduced elements of violence, ritual sacrifice, and even cannibalism that were not present in White’s originals, or significantly embellished details based on other, more sensationalized accounts. For instance, a peaceful scene of a dance might be reinterpreted to suggest a more pagan or wild ritual. The powerful impact of De Bry’s work cannot be overstated; his detailed, albeit often inaccurate, engravings became the definitive visual lexicon for generations of Europeans, shaping their understanding of the "New World" and its inhabitants.

A fascinating fact: De Bry’s alterations to John White’s original drawings are a stark illustration of the European interpretive lens. White’s image of a Carolina Algonquian village, for example, is transformed by De Bry to emphasize exoticism and difference, sometimes adding elements of European theatricality or classicism. The subtle lines and naturalism of White’s watercolors were often replaced by dramatic chiaroscuro and idealized forms in De Bry’s engravings, making the Native Americans appear both more exotic and more familiar to European viewers accustomed to classical art.

As the centuries progressed, and European colonization intensified, so too did the complexity of the artistic depictions, though the underlying European gaze remained. Artists like Jacques Le Moyne de Morgues, who accompanied a French expedition to Florida in the 1560s, also produced valuable, if still somewhat stylized, ethnographic records of the Timucua people. His work, like White’s, later underwent similar transformations when re-engraved by De Bry.

By the 18th century, with the Enlightenment in full swing, philosophical debates about human nature and the "state of nature" continued to influence artistic representations. The "Noble Savage" trope found renewed vigor, often romanticizing Native Americans as symbols of freedom and virtue, uncorrupted by modern society. Yet, this romanticization often served to exoticize and infantilize, denying Native Americans their agency and the complexities of their evolving relationship with European settlers. Simultaneously, the "Brutal Savage" continued to justify expansion and conflict, depicting Native Americans as obstacles to "progress" or as inherently violent, validating their displacement.

Another interesting fact: The iconic feather headdress, often associated with all Native Americans in popular culture, gained prominence in European art primarily through depictions of Plains tribes in the 19th century. However, earlier European art often depicted a more generic "feathered" appearance, sometimes with a full body feather suit, a style that was more allegorical than ethnographically accurate for many Eastern Woodlands tribes encountered first. This illustrates how a generalized exoticism often trumped specific cultural details.

In conclusion, early European art depicting Native Americans was a powerful, often beautiful, but fundamentally flawed construct. It was a product of discovery, curiosity, fear, and avarice, filtered through existing European aesthetic, philosophical, and theological frameworks. These images, rarely created by firsthand observers and frequently manipulated for political or commercial purposes, served to categorize, romanticize, demonize, and ultimately, to justify the subjugation of diverse indigenous peoples. The legacy of these early depictions is profound; they created a visual vocabulary that resonated for centuries, shaping not only European understanding but also, tragically, the very self-perception forced upon Native Americans within the colonial project. To truly understand this complex history, we must look beyond the surface of these captivating images and recognize the layers of European projection and power that they embody.