The Unseen Weapon: How Disease Decimated Native Americans in the Colonial Era

The narrative of European colonization in the Americas often centers on explorers, conquistadors, land grabs, and military might. Yet, beneath the clatter of steel and the roar of cannons, an invisible, far more devastating force was at work: disease. Long before sustained European settlement, a silent biological holocaust swept across the continents, decimating indigenous populations and fundamentally reshaping the course of history. This was not merely an unfortunate byproduct of contact; it was a demographic catastrophe, a "Great Dying" that cleared the path for colonial expansion and forever altered the cultural, social, and spiritual fabric of Native American societies.

When Christopher Columbus landed in the Bahamas in 1492, he inadvertently unleashed a biological exchange with consequences so profound they are difficult to fully grasp. The peoples of the Americas, having been geographically isolated for millennia, possessed no acquired immunity to the panoply of Eurasian and African pathogens that Europeans carried. Diseases like smallpox, measles, influenza, typhus, diphtheria, whooping cough, and bubonic plague, common childhood ailments in Europe, became instruments of mass destruction in the Americas, transforming vibrant civilizations into ghost lands.

Historian Alfred W. Crosby famously coined the term "virgin soil epidemics" to describe these events. Unlike populations in the Old World who had centuries to develop partial immunities through exposure and selection, Native Americans were biologically naive. When a disease like smallpox, with a typical mortality rate of 20-30% in immune populations, entered a virgin soil, it could kill 70-90% of those infected. The sheer scale of this mortality is almost unfathomable. Pre-Columbian population estimates for the Americas range widely, from 10 million to over 100 million. Regardless of the exact figure, most scholars agree that by 1650, the indigenous population had plummeted by as much as 90% in many regions.

Smallpox was arguably the most fearsome of these unseen invaders. Its characteristic pustules, fever, and excruciating pain were often followed by blindness, disfigurement, or death. It was highly contagious, spreading rapidly through respiratory droplets, and could persist on clothing or blankets for weeks. Eyewitness accounts from the time paint a grim picture. When Hernán Cortés marched on the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan in 1520, a smallpox epidemic, likely introduced by an infected African slave, swept through the city. The disease killed Cuitláhuac, the Aztec emperor, and weakened the remaining population, making them vulnerable to Spanish conquest. As Cortés himself later wrote, the epidemic "helped us more than anything else."

The impact was not limited to the Aztec Empire. In the Inca Empire, smallpox arrived in the 1520s, years before Francisco Pizarro’s arrival, killing Emperor Huayna Capac and sparking a devastating civil war over succession that left the empire fractured and ripe for conquest. In North America, waves of epidemics preceded and accompanied European settlement. The Wampanoag, the tribe that famously aided the Pilgrims at Plymouth, had been decimated by disease in the years prior to 1620, their villages emptied and fields overgrown. This, ironically, made the land appear "empty" to the arriving Europeans, fueling the myth of an uninhabited wilderness.

Beyond smallpox, other diseases wrought havoc. Measles, though often less lethal than smallpox, could still be devastating in virgin soil populations, particularly when compounded by other stresses. Influenza, a recurring scourge, caused widespread sickness and death. Typhus, spread by lice, thrived in conditions of war, displacement, and famine that often followed initial contact. Recent research, for instance, has suggested that the devastating "cocoliztli" epidemics that ravaged Mexico in the 16th century, killing millions, were caused by a virulent strain of Salmonella enterica (specifically, Paratyphi C), brought by Europeans.

The mechanisms of spread were varied. Direct contact with colonists, missionaries, and soldiers was a primary vector. But diseases also traveled along existing indigenous trade routes, often reaching communities long before they ever saw a European. A blanket traded from one tribe to another could carry smallpox spores hundreds of miles inland, turning a vital network of exchange into a conduit for death. Forced labor, displacement, and the concentration of people in missions or settlements further exacerbated the spread.

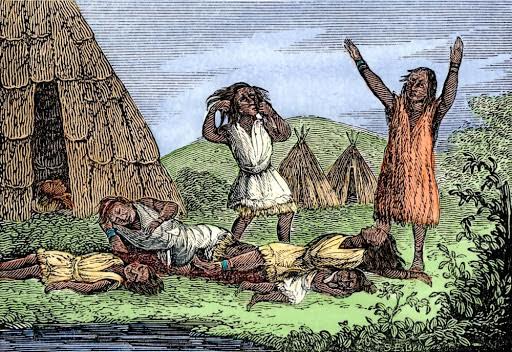

The cultural and social consequences of these epidemics were profound and far-reaching. The loss of 70-90% of a population was not merely a reduction in numbers; it was a societal collapse. Entire families, clans, and even tribes were wiped out. Oral histories, spiritual leaders, traditional healers, agricultural knowledge, and sophisticated governance structures vanished with the deaths of those who held them. Survivors were left traumatized, disoriented, and often without the critical mass needed to maintain their way of life.

The spiritual impact was equally devastating. In many Native American belief systems, illness was often attributed to spiritual imbalance or malevolent forces. The inability of traditional healers to combat these new, terrifying diseases led to a crisis of faith and a questioning of traditional worldviews. This spiritual vacuum, combined with physical weakness and societal breakdown, often made communities more susceptible to the proselytizing efforts of European missionaries.

The psychological toll was immense. Imagine witnessing nearly everyone you know—your parents, children, elders, friends—succumb to a horrific, unfamiliar illness. The despair, grief, and sense of powerlessness must have been overwhelming. This psychological scarring, passed down through generations, remains a hidden wound in many indigenous communities today.

Adding to the tragedy, there is evidence that disease was sometimes used, or at least contemplated, as a weapon. The most infamous example involves Lord Jeffrey Amherst, the British commander-in-chief in North America during Pontiac’s Rebellion (1763). In letters exchanged with Colonel Henry Bouquet, Amherst discussed the idea of deliberately infecting Native Americans with smallpox. On July 16, 1763, Amherst wrote, "Could it not be contrived to Send the Small Pox among those Disaffected Tribes of Indians?" Bouquet replied, "I will try to inoculate the Indians by means of Blankets that may fall in their hands, taking care however not to get the disease myself." While the direct efficacy and extent of this particular incident are debated, the sentiment reveals a horrifying willingness to exploit biological vulnerabilities.

The legacy of these colonial-era epidemics continues to resonate. They shattered indigenous societies, facilitating European conquest and settlement, and contributing to the enduring disparities and historical trauma faced by Native American communities. They challenge the romanticized notions of an "empty wilderness" waiting to be settled, revealing instead a landscape scarred by immense loss and the silent destruction of thriving civilizations.

Understanding the role of disease in the colonial period is crucial for a complete and honest accounting of American history. It highlights the vulnerability of isolated populations, the unintended (and sometimes intended) consequences of contact, and the enduring resilience of those who survived. The "Great Dying" was not merely a footnote; it was a foundational event, a tragic chapter written in sickness and death, that forever shaped the destiny of two continents and continues to inform our understanding of global health, historical justice, and the profound impact of biological exchange.