Echoes of the Ocmulgee: The Enduring Legacy of the Creek Nation in the American Southeast

The American Southeast, a landscape woven with verdant forests, meandering rivers, and ancient mounds, holds within its soil the indelible imprint of the Creek people. Known to themselves as the Muscogee (Mvskoke), the Creek Confederacy was not a monolithic tribe but a powerful and complex alliance of diverse towns and linguistic groups, bound by shared cultural practices and a common resolve to protect their ancestral lands. Their story is one of profound cultural heritage, strategic political maneuvering, devastating conflict, forced removal, and ultimately, inspiring resilience. From their pre-Columbian origins to their vibrant contemporary presence, the Creek Nation’s historical impact on the Southeast and the broader American narrative is both immense and often understated.

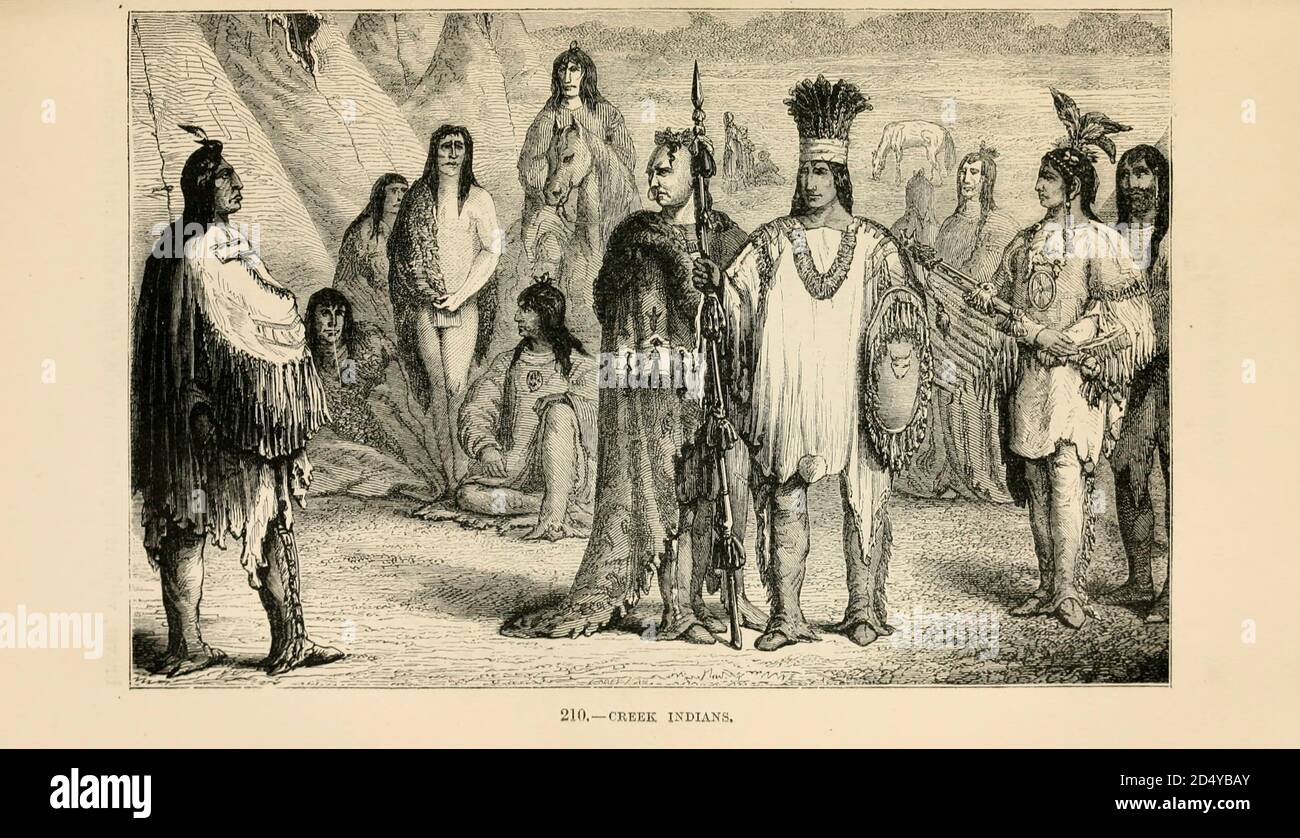

Ancient Roots and the Rise of a Confederacy

The roots of the Creek people stretch back millennia, intertwined with the Mississippian culture, responsible for the monumental earthworks that still dot the southeastern landscape. Sites like Etowah Mounds in Georgia and Moundville in Alabama bear witness to sophisticated societies with complex social structures, extensive trade networks, and rich ceremonial lives that predated European arrival by centuries. These ancestral groups, including the Apalachee, Alabama, Hitchiti, and others, eventually coalesced into what the English would come to call the "Creek" – a term derived from the Ochese Creek, near which many of their towns were located.

By the 16th century, when Europeans first penetrated the interior of the Southeast, the Creek Confederacy was a formidable political and military power. Their towns, often fortified, were self-governing entities, but they maintained strong diplomatic ties and a shared sense of identity. The Confederacy was broadly divided into two major geographical and political groupings: the Upper Creeks, concentrated along the Alabama and Tallapoosa rivers, and the Lower Creeks, located along the Chattahoochee and Flint rivers. This decentralized yet interconnected structure allowed for both internal autonomy and collective strength, making them adept at navigating the shifting tides of colonial power struggles.

A Crossroads of Empires: Navigating European Powers

The arrival of Hernando de Soto in the 1540s marked a catastrophic turning point, introducing diseases that decimated Native populations and foreshadowing centuries of conflict. However, for a significant period, the Creek demonstrated remarkable diplomatic skill in playing European colonial powers—Spanish, French, and British—against one another. Their strategic location, controlling vital trade routes and fertile lands, made them indispensable allies and formidable adversaries.

The 18th century saw the Creek Confederacy at the zenith of its influence in the region. They engaged in extensive deerskin trade with the British, exchanging furs for guns, tools, textiles, and other European goods. This trade fundamentally altered their economy and lifestyle, integrating them into a global market while also increasing their reliance on foreign goods. Their towns became centers of bustling commerce and cultural exchange.

"The Creek were not passive recipients of European influence," writes historian Robbie Ethridge in From Chicaza to Chickasaw. "They were active agents who shaped the colonial world as much as they were shaped by it." This agency was evident in their ability to maintain their sovereignty and cultural distinctiveness despite growing external pressures. Their sophisticated legal systems, communal land ownership, and matrilineal clan system, where lineage and property passed through the mother’s line, remained central to their identity. The Green Corn Ceremony, or Busk, a renewal festival, served as the spiritual and social anchor of their communities, reaffirming their connection to the land and to each other.

The Creek War and the Seeds of Removal

The turn of the 19th century brought unprecedented challenges. The young United States, driven by expansionist ambitions, cast an increasingly covetous eye on Creek lands. Tensions mounted as American settlers encroached, and the Creek found themselves caught in the geopolitical maelstrom of the War of 1812.

Internal divisions within the Creek Confederacy, exacerbated by the pressures of assimilation and land loss, erupted into a devastating civil war, often referred to as the Creek War (1813-1814). Inspired by Tecumseh’s pan-Indian resistance movement, a faction known as the "Red Sticks" advocated for a return to traditional ways and a militant stand against American expansion. They clashed fiercely with the "White Sticks," who favored accommodation and alliance with the U.S., often led by figures like William McIntosh, a prominent Lower Creek leader of mixed heritage.

The war culminated in the decisive Battle of Horseshoe Bend in March 1814, where a force led by General Andrew Jackson, comprising U.S. regulars, state militia, and allied Lower Creek and Cherokee warriors, crushed the Red Sticks. This brutal defeat effectively broke the military power of the Upper Creeks. The subsequent Treaty of Fort Jackson, imposed by Jackson, forced the Creek to cede over 23 million acres of land—more than half of their remaining territory—to the United States. This land grab significantly fueled the cotton kingdom’s expansion and set a grim precedent for future land cessions and removals.

The Trail of Tears: Forced Migration and Enduring Loss

Despite their service as U.S. allies during the Creek War, the remaining Creek lands continued to be targeted. The burgeoning demand for cotton land, coupled with racist ideologies that painted Native Americans as "savages" incapable of self-governance, fueled a relentless campaign for their removal. The Indian Removal Act of 1830, championed by President Andrew Jackson, formalized a policy that would systematically dispossess Native nations of their ancestral lands in the Southeast.

Through a series of coerced treaties, often signed by unrepresentative factions or under duress, the Creek were pressured to relinquish their remaining territories. The Treaty of Cusseta in 1832, for instance, allotted individual parcels of land to Creek families, a radical departure from their communal land ownership system, intended to fragment their society and facilitate eventual removal. When many refused to leave, the U.S. government deployed military forces to forcibly round up thousands of Creek people, including women, children, and the elderly, and march them westward.

The journey, part of what became known as the "Trail of Tears," was a harrowing ordeal. Under armed guard, enduring brutal conditions, disease, starvation, and exposure, thousands perished along the route to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma). It was a profound cultural trauma, severing the spiritual and physical ties of a people from lands they had inhabited for generations.

Resilience and Rebirth: The Creek Nation Today

Yet, the story of the Creek is not solely one of tragedy; it is also a testament to indomitable spirit and cultural tenacity. Upon arrival in Indian Territory, the Muscogee (Creek) Nation faced the daunting task of rebuilding their society, economy, and government. They re-established their towns, adapted their agricultural practices, and continued to practice their ceremonies, ensuring the survival of their distinct cultural identity.

Today, the Muscogee (Creek) Nation, headquartered in Okmulgee, Oklahoma, is one of the largest federally recognized tribes in the United States, with a vibrant and active government, robust economic enterprises, and a deep commitment to cultural preservation. They operate their own judicial system, schools, health clinics, and cultural centers. Efforts to revitalize the Mvskoke language, teach traditional arts, and educate new generations about their rich heritage are central to their mission.

Crucially, not all Creek people were removed. The Poarch Band of Creek Indians, located in Atmore, Alabama, represents a remarkable story of survival against overwhelming odds. These families, often by adapting to American ways, intermarrying, or retreating into remote areas, managed to hold onto their lands and maintain their cultural identity in their ancestral homeland. Today, the Poarch Band is the only federally recognized tribe in Alabama, a thriving community with diversified economic ventures, including casinos, which fund essential services and cultural programs for their people. Their very existence is a powerful counter-narrative to the prevailing narrative of complete removal.

An Enduring Legacy

The historical impact of the Creek people on the Southeast is undeniable. They shaped the region’s geography through their settlements and trade routes, influenced its early political landscape, and left an indelible mark on its cultural tapestry. Their struggle for sovereignty and self-determination continues to resonate, reminding us of the profound injustices of the past and the ongoing importance of Native American rights.

From the ancient mounds that whisper tales of their ancestors to the bustling tribal enterprises of today, the Creek Nation embodies a legacy of strength, adaptability, and unwavering commitment to their heritage. Their story serves as a vital reminder that history is not static, and that the echoes of the Ocmulgee continue to reverberate, enriching the American narrative with their enduring spirit. As the Muscogee (Creek) Nation asserts, "Our ancestors endured unimaginable hardship, but their spirit lives on in us. We honor them by preserving our language, our ceremonies, and our sovereignty, ensuring that the legacy of the Muscogee people continues to thrive."