The vast, unforgiving landscapes of Alaska’s Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta are home to the Yupik people, an Indigenous group whose existence has been intricately linked with the rhythms of the land and its creatures for millennia. Among these creatures, the caribou (Rangifer tarandus) stands as an undisputed cornerstone of their culture, providing sustenance, materials, and spiritual connection.

For the Yupik, caribou hunting is far more than a recreational activity or even a simple food-gathering exercise; it is a profound expression of their subsistence lifestyle, deeply embedded in their identity, traditions, and survival. This comprehensive guide delves into the historical and contemporary methods employed by the Yupik in their pursuit of caribou, highlighting the ingenuity, respect, and adaptability that define their approach.

Understanding Yupik caribou hunting requires an appreciation for the unique environment they inhabit. The tundra ecosystem, characterized by permafrost, low-growing vegetation, and extreme seasonal changes, dictates much about caribou migration patterns and, consequently, hunting strategies. The Yupik have developed an unparalleled understanding of this environment, passed down through generations.

Historically, caribou hunting was a matter of life and death, demanding immense skill, patience, and collective effort. Traditional knowledge, or Ella Nunam Tengeta (knowledge of the land and its resources), guided every aspect of the hunt, from tracking and stalking to processing and preserving the meat.

The Yupik people’s relationship with caribou is one of deep respect. Hunters approach the animals not as mere prey, but as fellow inhabitants of the earth, whose sacrifice provides for the community. This reverence is often expressed through rituals, prayers, and a commitment to utilizing every part of the animal, minimizing waste.

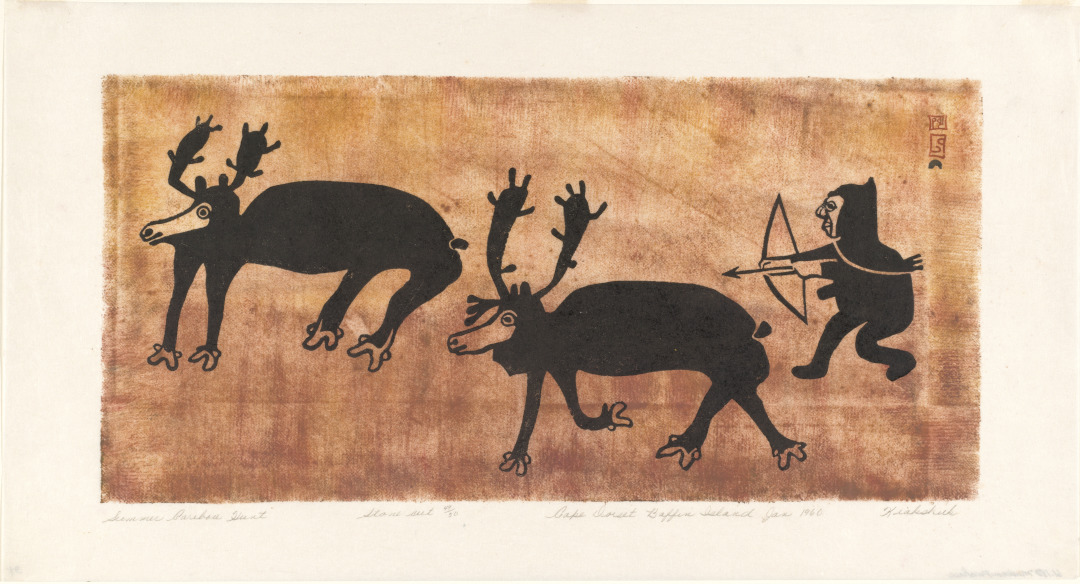

One of the earliest and most fundamental traditional hunting methods involved the use of spears and atlatls. The atlatl, a spear-thrower, extended the hunter’s arm, providing greater leverage and velocity for the spear, allowing for more effective hunting at a distance.

Bows and arrows were also critical tools, crafted from local materials like wood, bone, and sinew. Hunters would meticulously prepare their arrows, often fletching them with bird feathers and tipping them with sharpened stone or bone points, ensuring accuracy and lethality.

Snares and traps, strategically placed along known caribou trails or near water sources, offered another method for catching animals. These non-projectile methods required deep knowledge of caribou behavior and movement patterns to be effective.

The use of kayaks and other watercraft was particularly significant for hunting caribou during river crossings or when herds were driven towards water bodies. Hunters in kayaks could intercept swimming caribou, making them more vulnerable and easier to harvest.

Driving caribou into corrals or natural enclosures was another communal hunting technique. Large groups of hunters, often joined by women and children, would work together to funnel migrating herds into areas where they could be more easily taken, maximizing the harvest for the entire community.

The advent of European contact brought new technologies that gradually integrated into Yupik hunting practices. Firearms, initially rudimentary muzzleloaders and later more advanced rifles, revolutionized hunting efficiency and safety.

Modern transportation, such as snowmachines (snowmobiles) and all-terrain vehicles (ATVs), has significantly altered how hunters access remote areas and pursue caribou. These tools allow hunters to cover vast distances much faster than traditional methods, impacting the scope and logistics of the hunt.

Boats, including aluminum skiffs with outboard motors, have replaced or supplemented traditional kayaks, enabling hunters to navigate rivers and coastal areas more quickly, particularly during the crucial fall migrations when caribou cross major waterways.

Despite the adoption of modern tools, the core principles of Yupik hunting remain rooted in tradition. Hunters still rely heavily on their understanding of the environment, caribou behavior, and the wisdom passed down from elders. Technology is seen as an enhancement, not a replacement for traditional knowledge.

Seasonal variation plays a crucial role in Yupik hunting strategies. During the spring, hunters might focus on smaller, younger animals, while the fall migration periods offer opportunities for larger harvests as caribou move in massive herds.

Winter hunting, though more challenging due to harsh conditions, provides essential protein when other food sources are scarce. Hunters must contend with deep snow, extreme cold, and shorter daylight hours, demanding resilience and specialized cold-weather gear.

The concept of ‘sharing’ is central to Yupik hunting culture. A successful hunt benefits the entire community, with meat distributed widely, especially to elders, those unable to hunt, and families in need. This practice reinforces social bonds and ensures food security for everyone.

Processing caribou meat is an intensive, communal effort. Immediately after a successful hunt, the animal is butchered efficiently to prevent spoilage. Traditional methods of preservation, such as drying (making pammiaq) and smoking, are still widely practiced, alongside modern freezing techniques.

Beyond food, caribou provide a wealth of other resources. Hides are used for clothing, bedding, and shelter, offering unparalleled warmth in Arctic conditions. Antlers and bones are fashioned into tools, utensils, and artistic carvings. Sinew is used for thread and lashing.

The spiritual significance of caribou is profound. Many Yupik stories, dances, and ceremonies revolve around the animal, reflecting its central role in their worldview. There’s a deep belief in the spirit of the animal and the need to honor its gift.

Contemporary Yupik hunters face numerous challenges, including the impacts of climate change on caribou migration patterns and herd health. Shifting weather patterns, changes in vegetation, and altered ice conditions can make hunting more unpredictable and dangerous.

Government regulations and co-management agreements with state and federal agencies also play a significant role in modern hunting practices. The Yupik actively participate in these processes to ensure their subsistence rights are protected and that caribou populations are managed sustainably.

Conservation is an inherent part of Yupik hunting. The traditional worldview emphasizes living in harmony with nature and taking only what is needed. This intrinsic understanding of sustainability has preserved caribou populations for generations, long before modern conservation movements.

The health of caribou herds is a constant concern. Factors like disease, predator populations, and human impact are closely monitored by both Yupik hunters and wildlife biologists. Collaborative efforts are often undertaken to ensure the long-term viability of these vital herds.

For the Yupik, caribou hunting is not merely about sustenance; it is a profound act of cultural continuity. Each hunt is a reaffirmation of their connection to the land, their ancestors, and the future generations who will inherit these rich traditions.

In conclusion, Yupik caribou hunting methods represent a remarkable blend of ancient wisdom and contemporary adaptation. Rooted in deep respect for the animal and an intimate understanding of the Arctic environment, these practices ensure the survival and cultural vibrancy of the Yupik people.

From the ingenuity of early spear-throwers to the strategic use of modern technology, Yupik hunters exemplify resilience and resourcefulness. Their commitment to sustainable harvesting and community sharing serves as a powerful model for human-wildlife coexistence in a rapidly changing world.

The caribou remains an enduring symbol of life and endurance for the Yupik, a testament to a culture that has thrived for thousands of years by honoring the gifts of the land and passing on invaluable knowledge from one generation to the next.