The Enduring Spirit of the Yoeme: A Tale of Resilience Across the Arizona-Sonora Divide

From the arid riverbanks of Sonora to the bustling communities of Arizona, the Yaqui people, or Yoeme as they call themselves, have woven a narrative of profound resilience, unwavering cultural preservation, and a tenacious fight for sovereignty. Their history is not merely a chronicle of events, but a living testament to an enduring spirit that has navigated centuries of colonial conquest, brutal wars, forced displacement, and the artificial divide of an international border. To understand the Yaqui is to understand a people whose identity is inextricably linked to their ancestral lands, a sacred bond that has fueled their survival against overwhelming odds.

The story begins in the heartland of Sonora, Mexico, along the Río Yaqui, a fertile ribbon of life cutting through the desert landscape. Here, for millennia, the Yoeme cultivated their lands, developing a complex social, political, and spiritual system. They were a self-sufficient people, their worldview deeply rooted in the natural world, their ceremonies a vibrant expression of their spiritual connection to the land and its creatures, most famously epitomized by the revered Deer Dance. This pre-colonial harmony was shattered with the arrival of the Spanish in the early 17th century.

Initially, the Yaqui famously repelled Spanish military incursions, demonstrating their formidable martial prowess. However, the Jesuits, arriving in 1617, introduced a different kind of influence. Unlike many other Indigenous groups, the Yaqui largely invited the Jesuits, seeing potential benefits in new agricultural techniques and a buffering presence against Spanish settler encroachment. This era, lasting over a century, allowed the Yaqui to integrate elements of Catholicism into their existing spiritual framework, creating a unique syncretic religious tradition that remains central to their identity today. The Jesuits also helped solidify the Yaqui’s communal land ownership, creating a relatively autonomous Yaqui nation within the Spanish colonial system.

The expulsion of the Jesuits in 1767 marked a turning point, ushering in an era of increasing conflict with the Spanish, and later, the nascent Mexican state. Mexico’s independence in 1821, far from bringing liberation, intensified the struggle for the Yaqui. The new government, eager to exploit the fertile Yaqui River Valley for its own economic gain, systematically began to encroach upon Yaqui lands, disregarding the communal titles established under Spanish rule. This period ignited what became known as the Yaqui Wars, a series of protracted, brutal conflicts that spanned much of the 19th and early 20th centuries.

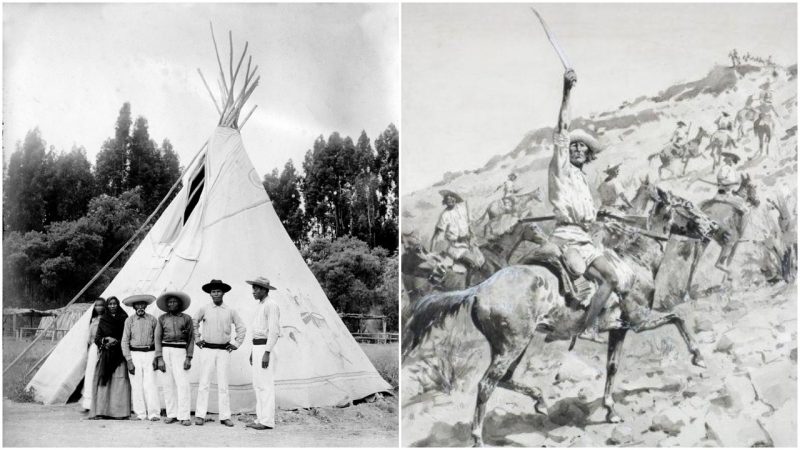

The Yaqui Wars were not simply battles over territory; they were a fight for survival, for cultural integrity, and for the very right to exist as a distinct people. Yaqui leaders like Cajeme (José María Leyva), a brilliant military strategist and charismatic leader of the late 19th century, emerged to lead their people in fierce resistance against overwhelming Mexican forces. Cajeme, whose name means "he who does not speak" in Yaqui, unified disparate Yaqui communities and even allied with other Indigenous groups, launching a formidable campaign that frustrated the Mexican government for years. His ultimate capture and execution in 1887, while a devastating blow, did not break the Yaqui spirit but rather solidified his place as a legendary figure of resistance.

The Mexican government’s response to Yaqui resistance was often savage. Driven by a desire to "civilize" or exterminate the Yaqui and appropriate their valuable lands, they implemented policies of forced removal, deportation, and even genocide. Thousands of Yaqui men, women, and children were rounded up and sent to forced labor camps in the distant Yucatán Peninsula and Oaxaca, a horrifying chapter in Mexican history that saw countless Yaqui perish from disease, overwork, and despair. This systematic attempt at cultural annihilation, however, inadvertently played a crucial role in shaping the Yaqui diaspora.

Facing certain death or enslavement, many Yaqui families made the perilous journey north, seeking refuge across the international border in the United States. This mass migration, primarily occurring in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, saw Yaqui refugees settle in various parts of Arizona, establishing new communities like Pascua, Guadalupe, Barrio Libre in Tucson, and others near Phoenix and Sonora. They arrived as undocumented immigrants, often facing discrimination and hardship, but they carried with them their language, their spiritual traditions, and an unshakeable determination to preserve their identity.

The US-Mexico border, a political line drawn across their ancestral migratory paths, thus created a unique situation: a single people divided by two nations, yet united by a shared history of struggle and an enduring cultural heritage. In Arizona, the Yaqui adapted, working in agriculture, mining, and railroads, quietly rebuilding their lives while fiercely guarding their traditions. Their elaborate Lenten and Easter ceremonies, which beautifully blend Catholic liturgy with ancient Yaqui spiritual practices, became powerful expressions of their cultural survival, drawing both reverence and curiosity from their non-Yaqui neighbors.

The struggle for recognition in the United States was a long and arduous one. For decades, the Yaqui in Arizona existed in a legal limbo, lacking federal recognition and the protections and resources that came with it. It wasn’t until 1978, after years of advocacy and legislative effort, that the Pascua Yaqui Tribe in Arizona finally achieved federal recognition, establishing a land base and the right to self-governance. This was a monumental victory, allowing the Arizona Yaqui to build schools, healthcare facilities, and economic enterprises, and to assert their sovereignty within the US legal framework.

Meanwhile, the Yaqui communities in Sonora continued their fight, often against renewed threats to their land and water rights. The Río Yaqui, the very source of their life, became a battleground for water allocation, with government projects diverting its flow to support large-scale agriculture and urban centers, often at the expense of the Yaqui communities downstream. The struggle continues today, with Yaqui leaders in Sonora battling against mining projects, industrial development, and the ongoing challenge of maintaining their traditional governance structures and cultural practices in the face of modern pressures.

Despite the political border and the divergent paths taken by their communities in two nations, the cultural ties between the Yaqui of Arizona and Sonora remain strong. Families traverse the border for ceremonies, for family gatherings, and to maintain the spiritual and linguistic connections that bind them. The Deer Dance, or Maaso Yi’iwame, performed by Yaqui men who embody the spirit of the deer, remains a powerful symbol of their spiritual beliefs and their enduring connection to the natural world, practiced with equal fervor on both sides of the border. It is a profound expression of their ancient cosmology, a sacred drama that reaffirms their identity and their place in the universe.

The Yaqui story is a powerful reminder of the human cost of colonialism and national expansion, but also of the indomitable strength of Indigenous cultures. Their history is not one of victimhood, but of agency, resistance, and an extraordinary capacity for adaptation and cultural resilience. From the defiant stands against Spanish conquistadors to the protracted Yaqui Wars, the perilous flight across the desert, and the ongoing battles for land and water rights, the Yaqui have demonstrated an unyielding commitment to their identity and their way of life.

Today, the Yaqui people continue to navigate the complexities of modernity while holding fast to their traditions. They face new challenges, from environmental degradation threatening their sacred landscapes to the pressures of assimilation and the ongoing fight for economic justice and political self-determination. Yet, their journey across the Arizona-Sonora divide stands as a vibrant testament to the enduring spirit of the Yoeme, a people who have refused to be erased, whose history echoes with the strength of their ancestors, and whose future promises the continued flourishing of a rich and profound cultural legacy. Their story is a living dialogue between the past and the present, a testament to the power of a people united by their sacred river, their ceremonies, and their unshakeable will to survive.