Echoes of Antiquity: Unveiling the Social Tapestry of Ancient Civilizations

The human story is an intricate mosaic, woven from countless threads of custom and tradition. Peering back into the annals of ancient civilizations reveals a world both startlingly alien and profoundly familiar, where the daily rhythms of life were dictated by social norms that shaped everything from greetings and meals to marriage and mortality. These customs, often born from necessity, spiritual belief, or the pursuit of order, provide a crucial window into the values, fears, and aspirations of peoples long past, painting a vivid picture of societies fundamentally different yet undeniably human.

From the sun-drenched banks of the Nile to the sprawling urban centers of Mesopotamia, the bustling agoras of Greece, and the grandeur of Imperial Rome, each civilization crafted a unique social compact. Understanding these customs isn’t merely an academic exercise; it’s a journey into the very heart of what it meant to be human thousands of years ago, challenging our modern assumptions and enriching our appreciation for the diverse tapestry of human experience.

Egypt: Life, Death, and the Pursuit of Order

Ancient Egypt, a civilization defined by its enduring monuments and a profound reverence for the afterlife, possessed a social fabric rich in ritual and hierarchy. At its core lay the family unit, with marriage often arranged but surprisingly egalitarian in terms of legal rights for women, who could own property, initiate divorce, and engage in business. While pharaohs might marry their sisters to maintain dynastic purity, commoners typically sought partners outside their immediate kin. Love was a celebrated emotion, immortalized in poetry: "I shall never be far from thee, so long as my hand is in thy hand."

Hygiene was paramount, driven by both practical needs in a hot climate and religious purity. Daily bathing, often multiple times, was common, and elaborate cosmetics, such as kohl eyeliner (used by both sexes for protection against the sun and perceived beauty), perfumed oils, and wigs, were essential for social presentation. Clothing, typically made of white linen, was simple yet elegantly draped, reflecting an emphasis on cleanliness and understated grace.

Dining was a communal affair, with beer and bread forming the staples. Banquets were elaborate, featuring a variety of meats, fruits, and vegetables, enjoyed while seated on cushions or low stools. Social etiquette dictated respect for elders and superiors, and the importance of contributing to Ma’at – the cosmic order and justice – permeated all social interactions. Death, however, was where Egyptian customs truly diverged. Mummification, an intricate and expensive process, was not merely a funeral rite but a social statement, ensuring the deceased’s passage to the afterlife and reflecting their status in life. The tomb, too, was a perpetual home, stocked with grave goods ranging from everyday items to opulent treasures, all designed to facilitate a comfortable existence in the next world.

Mesopotamia: Law, Hierarchy, and the Cradle of Civilization

In the fertile crescent of Mesopotamia, the birthplace of writing and urbanism, social customs were heavily influenced by the constant need for order in complex city-states and by a strong emphasis on law. The Code of Hammurabi, a Babylonian legal text from around 1754 BC, provides an unparalleled glimpse into these norms, explicitly detailing punishments based on social status. "If a man put out the eye of another man, his eye shall be put out. If he put out the eye of a commoner, or break the bone of a commoner, he shall pay one mina of silver." This "eye for an eye" principle, though harsh, aimed to establish a clear, albeit class-based, system of justice.

Mesopotamian society was rigidly hierarchical, with kings, priests, scribes, artisans, farmers, and slaves each occupying distinct strata. Marriage was an economic and social arrangement, often arranged by families, involving a dowry from the bride’s family and a "bride-price" from the groom. While polygyny was permitted, especially for wealthy men, the primary wife held significant status. Divorce was possible but more difficult for women, who were largely confined to the domestic sphere.

Trade and commerce were vital, and marketplaces bustled with activity. Early forms of contracts, receipts, and loans were common, reflecting a sophisticated economic system. Education, primarily focused on scribal training to manage administrative and religious texts, was a pathway to social mobility for a select few, typically boys from wealthier families. Religious festivals, often tied to agricultural cycles or lunar phases, provided communal gatherings, reinforcing social bonds and spiritual beliefs.

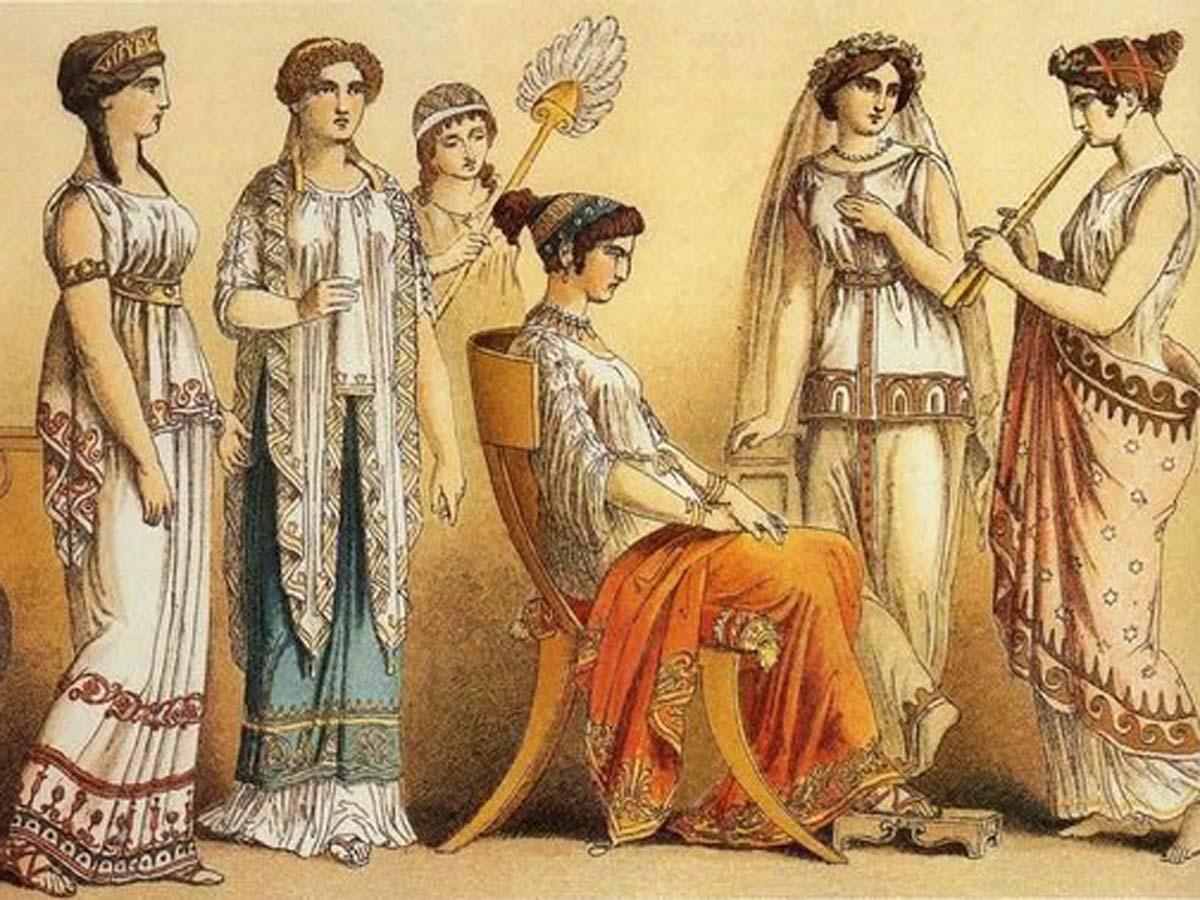

Greece: Civic Life, Philosophy, and Confined Women

Ancient Greece, a collection of independent city-states, exhibited fascinating variations in social customs, most notably between democratic Athens and militaristic Sparta. In Athens, civic life dominated. The agora (marketplace and public square) was the hub of social interaction, where men debated philosophy, conducted business, and engaged in political discourse. The gymnasium was not just for physical training but also a place for intellectual discussion and male bonding.

Hospitality, or xenia, was a sacred custom, demanding generous treatment of guests and protection of hosts. The Olympic Games, held every four years, transcended city-state rivalries, bringing Greeks together in a celebration of athletic prowess and shared culture.

Private life, however, was starkly different, particularly for women. Athenian women, especially those of the upper classes, were largely confined to the gynaeceum (women’s quarters), their primary role to manage the household and produce legitimate heirs. They rarely participated in public life and were expected to be modest and silent. Men, conversely, enjoyed the symposium, an exclusive drinking party where they engaged in intellectual conversation, poetry, and revelry, often accompanied by hetairai (educated courtesans) rather than their wives. The controversial practice of pederasty, a mentor-protégé relationship between an older man and an adolescent boy, was also a recognized, albeit debated, social custom among the elite.

Sparta, by contrast, prioritized military strength. Boys were taken from their families at age seven to begin rigorous state-sponsored training (agoge). Spartan women, while not involved in politics, enjoyed far greater freedom and physical education than their Athenian counterparts, as their primary role was to produce strong, healthy warriors. They could own land, manage estates, and move freely in public.

Rome: Family, Spectacle, and the Baths

The Roman Empire, a civilization renowned for its engineering, law, and military might, had a social structure deeply rooted in the concept of familia (family) and a pervasive client-patron system. The paterfamilias, the eldest male head of the household, wielded immense legal authority, even over adult children, though this power softened over time. Social advancement was often achieved through a network of patrons and clients, where the powerful offered protection and support in exchange for loyalty and service.

Public life was dominated by grand spectacles. Gladiatorial games, chariot races in the Circus Maximus, and theatrical performances were not merely entertainment but vital tools for social cohesion and political appeasement, encapsulated by the poet Juvenal’s famous phrase, "Panem et circenses" (bread and circuses). These events provided a common experience and a release valve for social tensions.

The Roman baths were central to daily life, serving as social hubs, gymnasiums, libraries, and places of hygiene. Romans would spend hours there, bathing, exercising, receiving massages, gossiping, and conducting business. Dining customs evolved, with elaborate banquets featuring multiple courses, often enjoyed reclining on couches in the triclinium. While the myth of the "vomitorium" for purging to eat more is largely exaggerated, lavish consumption was a mark of wealth and status. Roman women, though still under male guardianship, enjoyed more social freedom than their Greek predecessors. They could attend public spectacles, manage households, and socialize, often playing a significant, if informal, role in political life.

China: Filial Piety, Harmony, and Ritual

Ancient China, particularly under the influence of Confucianism, developed a social code emphasizing hierarchy, harmony, and ritual. The core principle was xiao (filial piety), demanding profound respect and obedience from children towards their parents and ancestors. This extended to the emperor, who was considered the "Son of Heaven" and the father figure of the entire nation. Ancestor worship was a central custom, with elaborate rituals performed to honor deceased family members, ensuring their well-being in the afterlife and the family’s prosperity.

Society was structured around the "Five Relationships" – ruler and subject, father and son, husband and wife, elder brother and younger brother, and friend and friend – each prescribing specific duties and decorum. Marriage was almost invariably arranged, not for love but to produce male heirs who would continue the family lineage and perform ancestral rites. The bride would leave her family to join her husband’s, often facing a period of subservience to her mother-in-law.

Etiquette was highly formalized, with strict protocols governing greetings, seating arrangements, and forms of address, all designed to maintain social harmony and reinforce hierarchy. While the controversial practice of foot binding emerged much later (around the Song Dynasty), its enduring impact highlights how deeply ingrained social customs could physically reshape women’s lives in pursuit of an ideal of beauty and status. Confucius’s timeless maxim, "Do not do to others what you do not want done to yourself," though an ethical principle, underpinned much of the desired social conduct.

Echoes and Enduring Legacies

Beyond these major civilizations, the Indus Valley Civilization, with its sophisticated urban planning and advanced sanitation, suggests a society prioritizing public health and communal living, though much of its social customs remain shrouded in mystery due to undeciphered writing. Mesoamerican cultures like the Maya and Aztecs developed intricate calendars, ballgames with ritual significance, and complex religious customs that included human sacrifice, reflecting a profound connection between their daily lives and cosmic cycles.

In examining these diverse social customs, a few common threads emerge: the enduring importance of family, the role of religion in shaping daily life, the establishment of social hierarchies, and the human need for order and belonging. While the specific manifestations varied wildly – from the rigid dictates of Hammurabi to the philosophical debates in the Athenian agora, or the reverent ancestor worship of China – these ancient societies, in their unique ways, sought to define what it meant to live together, to thrive, and to make sense of their world.

Today, these echoes of antiquity remind us that our own social norms are but one iteration in a long, evolving story of human interaction. They challenge us to look beyond our contemporary lens, fostering an appreciation for the remarkable ingenuity and adaptability of the human spirit in forging diverse paths to social cohesion and cultural identity. The customs of the ancients are not just historical footnotes; they are profound reflections of the perennial questions that continue to shape human society.