Turtle Island: A Foundation for Understanding Beyond the Colonial Map

For many non-Indigenous people living in what is commonly known as North America, the term "Turtle Island" might evoke a quaint myth, a poetic metaphor, or perhaps an unfamiliar concept altogether. Yet, for hundreds of Indigenous nations across this vast continent, Turtle Island is not merely a name; it is a foundational worldview, a spiritual home, and a powerful symbol of identity, resilience, and interconnectedness that predates colonial borders and narratives by millennia. Understanding Turtle Island is not just about learning a new geographical term; it is about grasping a profound truth that reorients our collective history and future.

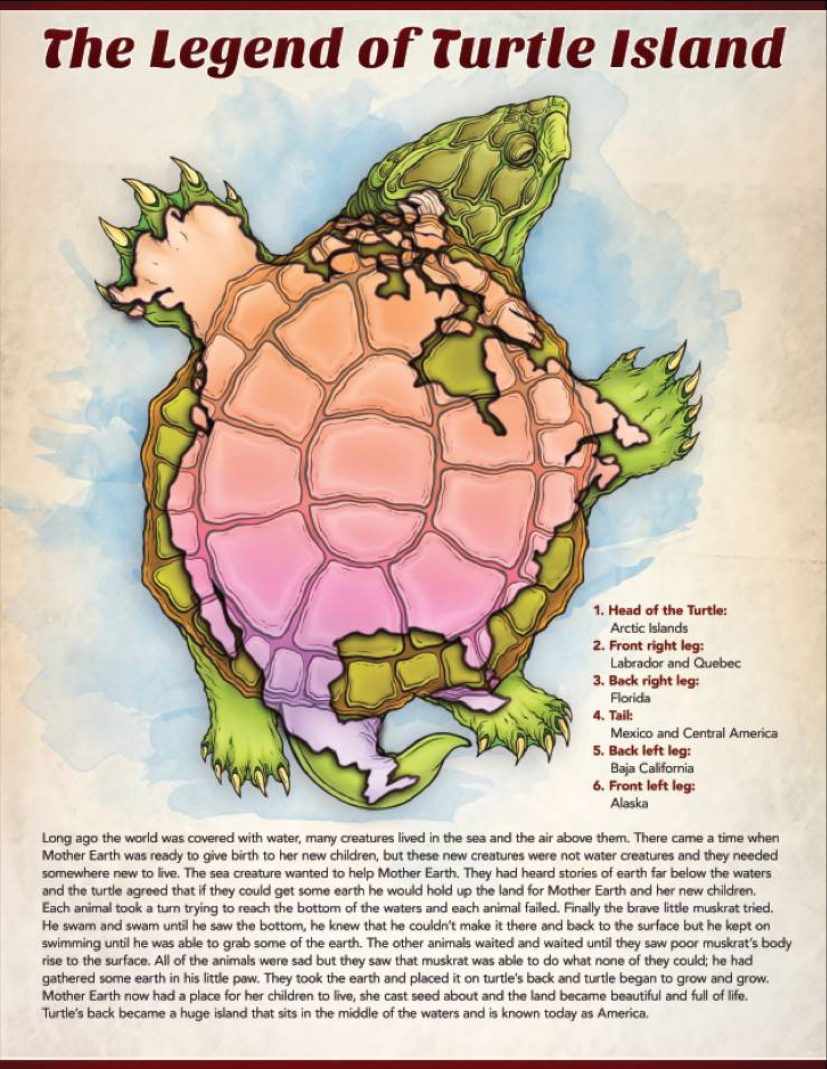

At its heart, Turtle Island refers to the landmass that non-Indigenous people now call North America. But its significance goes far deeper than mere cartography. For many Woodland nations, particularly the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) and Anishinaabe peoples, the name stems from a widely shared creation story. In these narratives, a Sky Woman falls from the heavens onto a primordial ocean. Various animals attempt to bring earth from the depths to create a place for her to land. Eventually, the Muskrat or Beaver succeeds, placing the earth on the back of a giant turtle, which then grows to become the continent we inhabit. This origin story imbues the land with sacredness, establishes a profound relationship between humans and the natural world, and underscores a fundamental principle: the land is a living entity, a generous provider, and a shared responsibility. It is a story of reciprocity, not ownership.

A Tapestry of Nations, Not a Blank Slate

Before the arrival of Europeans, Turtle Island was a vibrant, complex continent teeming with an estimated 7 to 18 million, and by some estimates up to 100 million, inhabitants. It was home to hundreds of distinct nations, each with its own language, governance structures, spiritual practices, scientific knowledge, art forms, and intricate social systems. From the highly organized city-states of Cahokia (near modern-day St. Louis), which rivaled London in population in the 13th century, to the sophisticated agricultural practices of the Haudenosaunee, the intricate trade networks spanning thousands of miles, and the astronomical observatories of the Ancestral Puebloans, Indigenous societies were anything but primitive. They were innovators, engineers, artists, philosophers, and stewards of the land, cultivating biodiversity and living in sustainable balance for thousands of years.

The notion that Europeans "discovered" a "new world" or a "wilderness" is a colonial fabrication designed to justify dispossession. This land was already discovered, already settled, and already thriving. The term "Turtle Island" serves as a crucial reminder of this deep history, asserting Indigenous presence and sovereignty long before the arrival of colonial flags and claims.

The Unfolding of Colonization: A Story of Violence and Resistance

The arrival of Europeans brought not just new peoples but a fundamentally different worldview. Concepts of private land ownership, resource extraction without regard for ecological balance, and a hierarchical social structure driven by racial superiority clashed violently with Indigenous principles of communal stewardship, reciprocity, and interconnectedness. The consequences were catastrophic: disease epidemics that decimated populations (some estimates suggest up to 90% mortality in the initial waves), brutal wars of conquest, forced removals (like the Trail of Tears), and the systematic destruction of cultures and languages.

The residential school system in Canada and the boarding school system in the United States stand as stark examples of this genocidal project. For over a century, hundreds of thousands of Indigenous children were forcibly removed from their families, forbidden to speak their languages, practice their spiritual traditions, or express their cultural identities. The stated goal, chillingly articulated by Canada’s first Prime Minister John A. Macdonald, was to "take the Indian out of the child." These institutions were sites of immense physical, emotional, and sexual abuse, leaving generations with intergenerational trauma that continues to impact Indigenous communities today. The discovery of thousands of unmarked graves at former residential school sites serves as a grim testament to this dark chapter, a truth that non-Indigenous people must confront directly and unflinchingly.

Resilience, Revitalization, and the Ongoing Fight for Sovereignty

Despite centuries of sustained assault, Indigenous peoples on Turtle Island have not only survived but are thriving, revitalizing their cultures, languages, and traditional governance systems. This resilience is a testament to the strength of their connection to the land and their ancestors. Today, there are over 630 First Nations in Canada and 574 federally recognized tribes in the United States (with many more state-recognized and unrecognized nations), each working to assert their inherent rights and self-determination.

The struggle continues on many fronts:

- Land Back: A movement calling for the return of ancestral lands to Indigenous stewardship, recognizing that land is not merely property but the foundation of culture, spirituality, and well-being.

- Treaty Rights: The ongoing fight to uphold and enforce the treaties signed between Indigenous nations and colonial governments, which were often broken or ignored by the Crown/state. These treaties are living agreements, not historical relics.

- Environmental Justice: Indigenous communities are disproportionately affected by environmental degradation and climate change, often living on the front lines of resource extraction projects. Their traditional knowledge offers vital solutions for environmental stewardship.

- Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, Girls, and Two-Spirit People (MMIWG2S+): A crisis rooted in systemic racism, colonialism, and gender-based violence, demanding urgent action and justice.

- Cultural Revitalization: Efforts to reclaim and teach Indigenous languages, ceremonies, art, and traditional practices, often after generations of suppression.

What Non-Indigenous People Should Know and Do

Understanding Turtle Island means more than just acknowledging a historical name; it means internalizing a different way of relating to the land and its original peoples. Here are crucial takeaways for non-Indigenous individuals:

- Acknowledge and Respect Land: Learn whose traditional territory you reside on. Understand that "land acknowledgements" are not mere formalities but calls to action, requiring a deeper engagement with the history and ongoing presence of Indigenous peoples. This means moving beyond a performative statement to actual relationship building and support.

- Educate Yourself Continually: Seek out Indigenous voices, books, documentaries, and news sources. Learn about specific nations, their histories, cultures, and current issues. Challenge your own biases and assumptions. This is not a one-time task but a lifelong journey.

- Challenge Colonial Narratives: Recognize that much of what is taught as "history" is a colonial narrative that erases or distorts Indigenous experiences. Actively decolonize your understanding of history, governance, and environmental ethics.

- Support Indigenous Sovereignty: Understand that Indigenous peoples have inherent rights to self-determination. Support their efforts to reclaim land, protect their territories, revitalize their cultures, and govern themselves according to their own laws and traditions. This can include supporting Indigenous businesses, artists, and political movements.

- Be an Ally, Not a Saviour: Listen more than you speak. Follow Indigenous leadership. Your role is to amplify Indigenous voices and support their self-determined goals, not to dictate solutions or appropriate their struggles.

- Understand Reciprocity: Shift from a mindset of extraction and consumption to one of reciprocity and stewardship. The Indigenous relationship with Turtle Island emphasizes giving back, caring for the land, and living in balance, lessons critical for addressing global environmental crises.

The concept of Turtle Island offers a profound invitation: to shed the blinkers of colonial history and embrace a richer, more accurate understanding of the land beneath our feet and the vibrant cultures that have nurtured it for millennia. It is a call to recognize the enduring sovereignty of Indigenous nations, to grapple with the ongoing impacts of colonialism, and to work towards a future built on justice, respect, and genuine reconciliation. For non-Indigenous people, embracing Turtle Island is not just about learning a name; it is about committing to a new way of seeing, listening, and being in relationship with this sacred continent and all its inhabitants. It is the foundation for building a truly shared and equitable future.