Echoes of an Ancient Dawn: Watson Brake, America’s Oldest Mounds, Reshape Prehistory

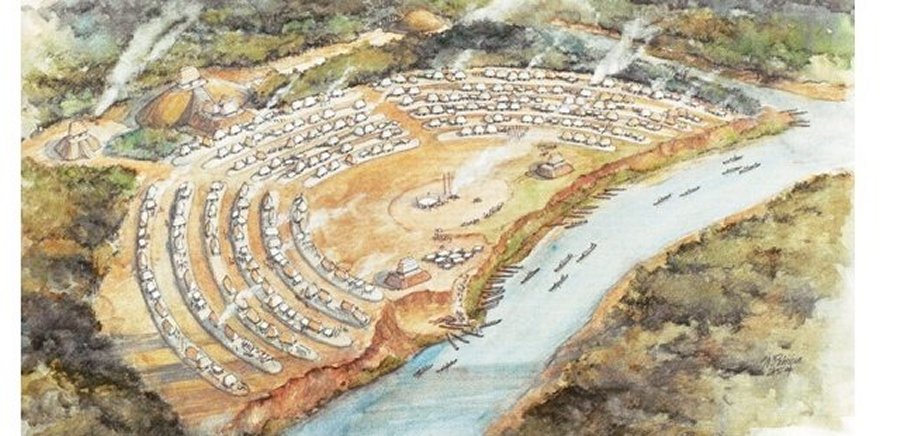

In the humid, verdant heart of northeast Louisiana, amidst the bayous and cypress swamps, lies a subtle yet profound testament to human ingenuity and communal spirit that predates the pyramids of Egypt and the megaliths of Stonehenge. Watson Brake, a seemingly unassuming cluster of eleven earthen mounds arranged in a large oval, whispers stories from an epoch so ancient it forces us to fundamentally rethink the origins of complex societies in North America. Dating back an astonishing 5,400 years (approximately 3400 BCE), these mounds represent the oldest known monumental earthworks in the Americas, a stark challenge to long-held archaeological paradigms and a window into the sophisticated lives of prehistoric hunter-gatherers.

For centuries, the prevailing archaeological wisdom held that the construction of monumental architecture – large, planned structures requiring significant labor and social organization – was exclusive to settled agricultural societies. The logic was simple: only a surplus of food and a sedentary lifestyle could support the specialized labor and hierarchical structures needed for such ambitious projects. Watson Brake shatters this assumption. Its builders were not farmers tending fields of maize; they were mobile hunter-gatherers, fishing in the nearby Ouachita River, hunting deer and small game, and foraging for wild plants. Their ability to conceive, plan, and execute such an enormous undertaking speaks volumes about their social complexity, environmental knowledge, and a shared vision that transcends mere subsistence.

The story of Watson Brake’s modern rediscovery is as intriguing as the mounds themselves. While local residents had long been aware of the low-lying bumps on the landscape, their true antiquity and significance remained unrecognized. It wasn’t until the early 1980s that a local timber company surveyor, Reca Jones, noticed the peculiar arrangement of the mounds while reviewing aerial photographs. Intrigued, Jones contacted Dr. Joe Saunders, an archaeologist at the University of Louisiana at Monroe. Saunders, initially skeptical, soon began to investigate. Early radiocarbon dating of charcoal found within the mounds yielded dates that were almost unbelievable – pushing back the timeline for monumental construction in North America by thousands of years. The initial findings were so revolutionary that they faced considerable resistance within the archaeological community, forcing Saunders and his team to meticulously re-examine and re-verify their data, ultimately publishing their groundbreaking work in the journal Science in 1997.

What Dr. Saunders and his team uncovered is a site of remarkable precision and purpose. The eleven mounds, ranging in height from 3 to 25 feet, are interconnected by a low, ring-shaped embankment, forming an oval approximately 900 feet in diameter. This arrangement is not random. Archaeological analysis suggests the mounds were built over a period of several hundred years, likely through seasonal communal gatherings. The builders used simple tools – baskets, deer antlers, and their own hands – to move immense quantities of earth, carefully selected from different soil types to create stable structures. The sheer logistical challenge of constructing these earthworks without beasts of burden or metal tools is staggering, requiring a highly organized society capable of coordinating hundreds, if not thousands, of individuals.

The precise function of Watson Brake remains a subject of ongoing debate and fascination. While the exact purpose may forever elude us, archaeologists hypothesize several possibilities. The deliberate placement of the mounds suggests potential astronomical alignments, perhaps marking solstices or equinoxes, which would have been crucial for tracking seasons and coordinating communal activities. It’s plausible the site served as a ceremonial center, a sacred space for rituals, gatherings, and perhaps burials, though no human remains have been definitively linked to the mounds themselves. It may have also functioned as a territorial marker, signifying the presence and collective identity of a specific group of people in the landscape. "These mounds weren’t just piles of dirt," explains Dr. Saunders, "they were statements – about community, about belief, about their relationship to the cosmos."

The implications of Watson Brake extend far beyond its geographical boundaries. It forces archaeologists to re-evaluate the evolutionary trajectory of human societies. The traditional narrative of progress, moving linearly from mobile hunter-gatherers to settled farmers and then to complex urban centers, is challenged. Watson Brake demonstrates that hunter-gatherer societies were far more complex and capable than previously imagined, possessing the social cohesion, organizational skills, and perhaps even the leisure time to undertake monumental construction. This suggests that the development of complex social structures might not be solely dependent on agricultural surplus but could arise from other factors, such as rich natural resources, a shared spiritual worldview, or the need for large-scale communal cooperation for purposes yet fully understood.

The people who built Watson Brake were adept at exploiting the abundant resources of their environment. The Ouachita River and its surrounding wetlands provided a reliable source of fish, shellfish, and migratory birds. The forests offered deer, wild fruits, and nuts. This rich resource base, while not agricultural, likely provided enough seasonal surplus to support periodic aggregations of people necessary for construction. They would gather at Watson Brake, perhaps during specific seasons, to build, celebrate, and reaffirm their communal bonds, before dispersing again to their smaller, more mobile camps. This pattern of seasonal aggregation and dispersal for large-scale projects is a fascinating insight into their adaptive strategies.

Watson Brake also offers a crucial precedent for understanding later, more extensive mound complexes in North America, such as Poverty Point, another UNESCO World Heritage site in Louisiana, which dates to approximately 1600 BCE. While Poverty Point is significantly larger and more elaborate, Watson Brake demonstrates that the tradition of monumental earthwork construction has deep roots in the region, a legacy passed down through generations. It shows that the desire to shape the landscape for cultural or spiritual purposes was present from the earliest times, long before the emergence of large-scale agricultural societies.

Today, Watson Brake remains largely on private land, limiting public access and presenting ongoing challenges for its long-term preservation. Its delicate contours are easily disturbed by modern activities, and the subtle nature of the mounds means they are vulnerable to being overlooked or damaged. Efforts continue to ensure its protection and to further unravel its mysteries through non-invasive archaeological techniques like remote sensing and geophysical surveys. Each new discovery, each piece of charcoal or ancient tool unearthed, adds another brushstroke to the portrait of these ancient engineers.

In a world increasingly focused on the fleeting present, Watson Brake stands as a powerful reminder of the enduring legacy of our ancestors. It is a silent sentinel, a monumental achievement forged by ingenuity, cooperation, and a profound connection to the land and sky, thousands of years before the written word or the wheel reached this continent. As we gaze upon these subtle hills, we are invited to ponder the aspirations, beliefs, and collective spirit of people who lived in a world utterly different from our own, yet who, like us, sought to leave their mark on the earth, whispering their stories across millennia. Watson Brake isn’t just a site; it’s a testament to the astonishing depth of human history and the boundless capacity for innovation inherent in even the earliest societies.