The Unbroken Promise: Water Protectors, Turtle Island, and the Sacred Fight for Life

Across the vast and diverse landscapes known to its Indigenous peoples as Turtle Island – a name carrying spiritual and historical weight for countless First Nations, Native American, and Inuit communities – a relentless battle is being waged. It is a battle for the very essence of life, for the sacred waters that sustain all beings, and for the inherent right to self-determination. At the heart of this struggle are the Water Protectors, a movement born from a profound spiritual connection to the land and a fierce determination to safeguard the future for generations to come. Their rallying cry, Mni Wiconi – "Water is Life" – echoes from the prairies to the mountains, a universal truth pitted against the relentless forces of resource extraction.

Turtle Island is more than just a geographical designation for North America; it is a living entity, imbued with spiritual significance, the ancestral home where creation stories are rooted and ancient covenants with the land and water were forged. For Indigenous peoples, water is not a commodity to be bought, sold, or polluted; it is a relative, a sacred being with its own spirit, an indispensable part of the circle of life. This worldview stands in stark contrast to the dominant industrial paradigm that views natural resources primarily through the lens of economic exploitation and profit. This fundamental divergence in understanding forms the bedrock of the conflict.

The Water Protectors movement gained global prominence in 2016-2017 at Standing Rock, North Dakota. The Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, joined by thousands of Indigenous people from hundreds of nations and non-Indigenous allies, rose up against the construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL). This pipeline was slated to transport 570,000 barrels of crude oil per day from the Bakken oil fields to Illinois, crossing sacred burial grounds and threatening the tribe’s primary water source, the Missouri River, just half a mile upstream from their reservation.

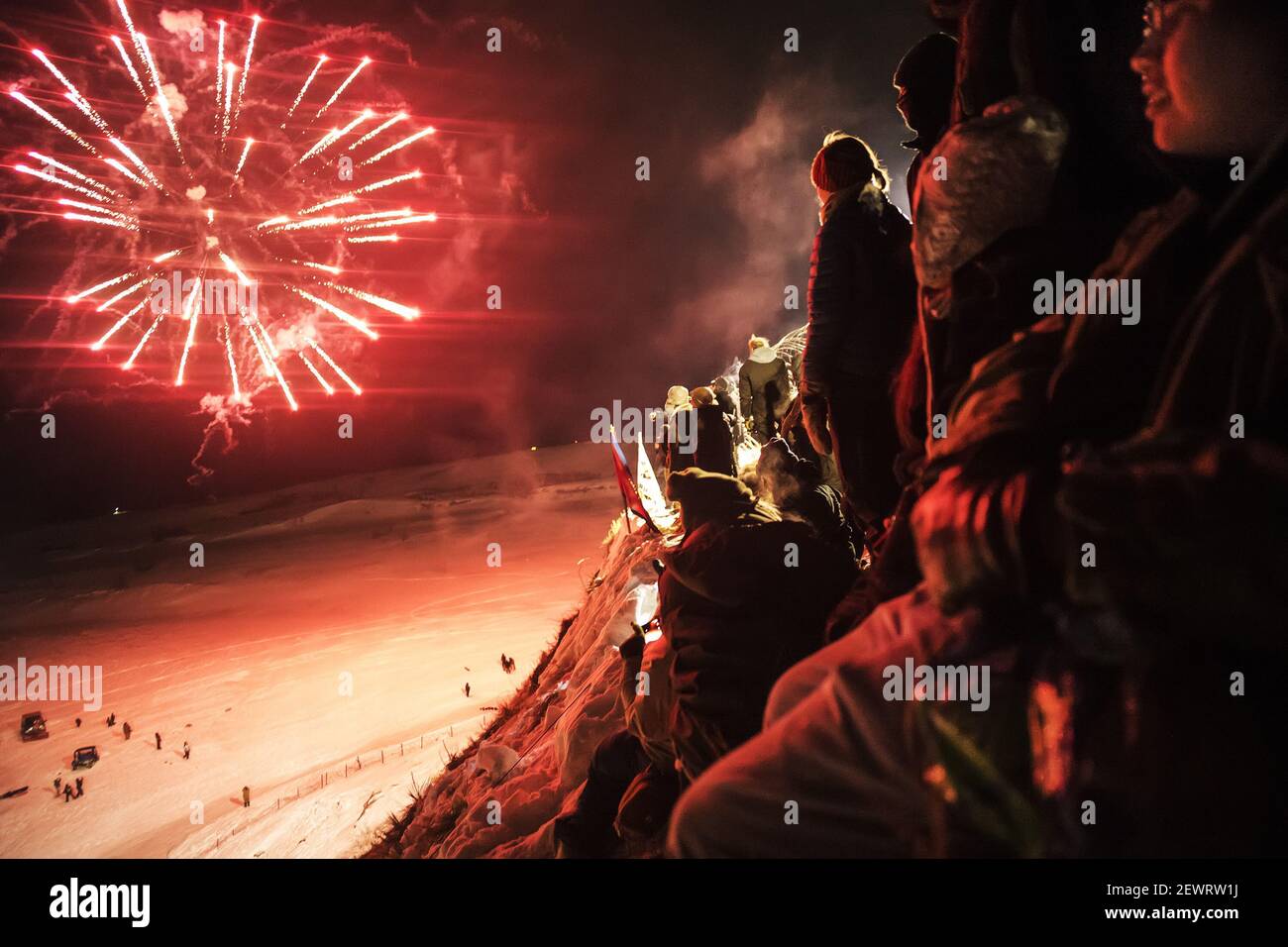

The Oceti Sakowin camp, established on treaty land, became a beacon of resistance. Elders, youth, spiritual leaders, and warriors gathered, not as protestors, but as protectors, engaging in prayer, ceremony, and direct action. LaDonna Brave Bull Allard, a founder of the Sacred Stone Camp, articulated the stakes with clarity: "My people have lived here for thousands of years. We have fought for our land and water since the coming of the white man. We are still fighting. We are fighting for our children and our grandchildren. We are fighting for the water, for all life." The world watched as peaceful protectors were met with an escalating militarized response from private security and state law enforcement, deploying water cannons in freezing temperatures, rubber bullets, tear gas, and attack dogs. Yet, the spirit of Mni Wiconi endured, drawing unprecedented international attention to Indigenous rights and environmental justice.

While DAPL eventually became operational despite the protests, the fight at Standing Rock ignited a powerful, enduring flame. It showcased the strength of Indigenous sovereignty, the power of prayerful resistance, and the urgent need to protect water from extractive industries. It also exposed the stark reality of how corporations, often backed by state power, prioritize profits over environmental safety and treaty obligations. The legacy of Standing Rock is not just about one pipeline; it’s about a renewed commitment to defending water across Turtle Island.

One of the most significant ongoing struggles in the wake of Standing Rock is the resistance to Enbridge’s Line 3 pipeline in northern Minnesota. Line 3 is an expansion of an aging, corroding pipeline, designed to carry nearly a million barrels of tar sands oil daily from Alberta, Canada, across Ojibwe treaty lands to a terminal in Wisconsin. This project poses an existential threat to the headwaters of the Mississippi River, countless pristine lakes, and the crucial wild rice (Manoomin) beds that are central to Anishinaabe culture, diet, and spiritual life. Wild rice, a sacred food, is highly sensitive to water quality and changes in hydrology, making the pipeline an immediate danger to food security and cultural survival.

Indigenous leaders like Winona LaDuke of Honor the Earth have been at the forefront of this resistance, emphasizing the direct violation of treaty rights and the catastrophic potential for spills. "This is a climate change pipeline, a treaty rights pipeline, a human rights pipeline," LaDuke asserts, highlighting the multifaceted nature of the struggle. "We are standing up for water, for wild rice, for our future." The tactics employed by Water Protectors at Line 3 mirror those at Standing Rock: prayer camps, direct action, legal challenges, and cultural revitalization. Again, they have faced arrests, harassment, and an aggressive response from law enforcement, funded in part by Enbridge itself.

Beyond these high-profile battles, Water Protectors are active on countless fronts across Turtle Island. From the Wet’suwet’en territory in British Columbia, where hereditary chiefs resist the Coastal GasLink pipeline, to the fight against mining projects in the pristine Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness, the pattern is consistent: Indigenous communities, often on the front lines of climate change impacts, are forced to defend their ancestral lands and waters from projects that prioritize short-term economic gain over long-term ecological health.

The core of the Water Protectors’ philosophy is deeply rooted in the concept of "Seven Generations." This Indigenous principle dictates that decisions made today should consider the impact they will have on the next seven generations. When considering a project like an oil pipeline with a projected lifespan of decades and the potential for spills that can render water unusable for centuries, the conflict with this long-term stewardship ethic becomes starkly apparent. The environmental damage caused by oil and gas infrastructure—from the extraction process to potential spills—disproportionately affects Indigenous communities who often live closest to these sites and rely directly on the land and water for their livelihoods and cultural practices.

Moreover, the presence of "man camps" – temporary housing for transient pipeline workers – has been linked to a documented increase in violence against Indigenous women, girls, and two-spirit people. The Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG) crisis is an epidemic across North America, and the influx of non-local workers into remote areas often exacerbates existing vulnerabilities, leading to increased rates of sexual assault, trafficking, and murder. For Water Protectors, defending the land and water is intrinsically linked to protecting their communities and the lives of their relatives.

The legal and political dimensions of these struggles are complex. Many pipeline projects traverse lands covered by historic treaties, agreements signed between Indigenous nations and colonial governments that often guaranteed rights to hunt, fish, and gather, and to the peaceful enjoyment of their lands. These treaties, frequently disregarded or reinterpreted by modern governments, are the legal bedrock of Indigenous sovereignty. Water Protectors and their legal teams continually challenge permits and approvals, citing violations of treaty rights, environmental regulations, and inadequate consultation processes. The fight is not just about stopping a pipeline; it’s about upholding the rule of law and respecting the inherent rights of Indigenous nations.

The journalistic lens on these movements often focuses on the direct actions and confrontations, but it is crucial to understand the deep spiritual and cultural underpinnings. Prayer, ceremony, song, and traditional teachings are not just components of the movement; they are the movement. Elders provide guidance and historical context, youth bring energy and a fierce commitment to their future, and the collective engagement in traditional practices strengthens resolve and fosters resilience. The camps are often places of cultural revitalization, where languages are spoken, stories are shared, and the bonds of community are reinforced.

The Water Protectors movement represents a paradigm shift in environmental activism. It centers Indigenous leadership, knowledge, and spiritual connection to the land. It highlights the interconnectedness of environmental degradation, human rights abuses, and colonial legacies. It forces a reckoning with the true costs of fossil fuel dependence and calls for a transition to sustainable, respectful ways of living.

As climate change accelerates and the need for clean water becomes ever more critical, the voice of the Water Protectors on Turtle Island grows louder and more urgent. Their struggle is not merely for their own communities but for all humanity, for the health of the planet itself. They stand as guardians of the sacred, reminding us that water is indeed life, and its protection is a collective responsibility that transcends borders, cultures, and generations. The unbroken promise of Turtle Island demands nothing less than an unwavering commitment to its waters and the future they sustain.