Echoes of the River, Voices of Resilience: The Enduring History of Oregon’s Warm Springs Tribes

Nestled in the high desert plateaus and river valleys of Central Oregon, the lands of the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs (CTWS) bear witness to a history as ancient and enduring as the Columbia River itself. This sovereign nation, a vibrant tapestry woven from the distinct cultures of the Wasco, Warm Springs (Tenino/Tygh), and Northern Paiute peoples, represents not merely a tale of survival, but a testament to profound resilience, cultural tenacity, and an unyielding connection to ancestral lands that spans millennia. Their narrative is a powerful reminder of the deep roots of Indigenous peoples in North America and their ongoing journey of self-determination in the face of immense historical pressures.

Ancient Roots and Abundant Lands: A Pre-Contact Legacy

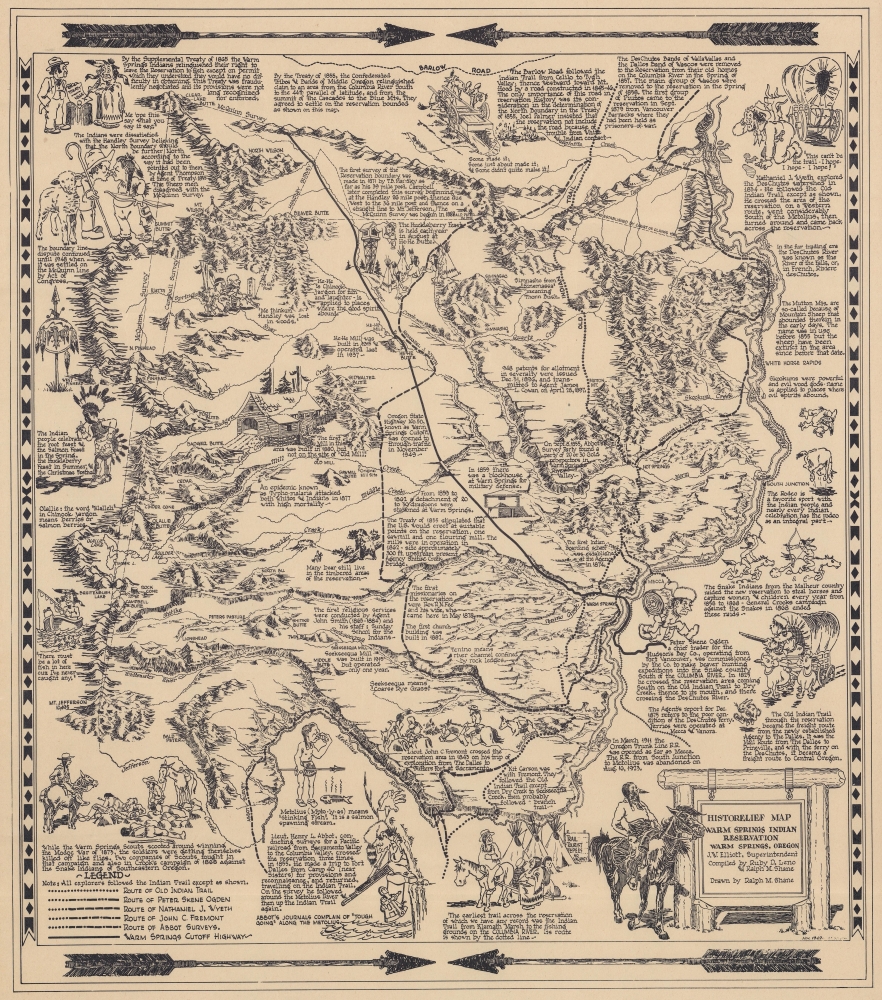

Before the arrival of Euro-Americans, the three distinct tribes that would eventually form the Confederated Tribes thrived across an expansive, resource-rich territory. The Wasco people, primarily residing along the Columbia River, were renowned traders and fishermen, their lives intimately tied to the river’s bounty, especially the salmon. Their language, Kiksht, is part of the Chinookan family. Further south and east, the Warm Springs (Tenino/Tygh) people of the Sahaptin linguistic group, occupied the tributaries of the Deschutes River and the surrounding plateau. They were skilled hunters and gatherers, following seasonal rounds for deer, elk, camas roots, and berries. To the east and south, the Northern Paiute people, speaking a Numu language of the Uto-Aztecan family, traversed the arid Great Basin, adapting their nomadic lifestyle to its challenging environment, relying on small game, roots, and seeds.

The Columbia River served as the beating heart of their spiritual, social, and economic life for millennia. Celilo Falls (Wyam), the ancient ‘Great Mart’ of the Columbia, was a vibrant hub where tribes from across the Pacific Northwest and beyond gathered to fish, trade, and socialize. It was a place of immense spiritual significance, a sacred site where the very essence of their existence was renewed with each salmon run. "The river was our highway, our grocery store, our church," a Warm Springs elder might have said, reflecting the deep reverence and reliance on this powerful waterway. This intricate network of trade, ceremony, and kinship characterized a sophisticated and sustainable way of life that had evolved over thousands of years, long before any European set foot on the continent.

The Shifting Sands of Treaty and Reservation: 19th Century Transformations

The mid-19th century brought an irreversible shift. The relentless westward expansion of American settlers, coupled with the devastating impact of European diseases, began to erode the traditional lifeways of Indigenous peoples. The year 1855 marked a pivotal, and painful, turning point for the Warm Springs, Wasco, and Northern Paiute. Under immense pressure from the U.S. government, represented by Superintendent of Indian Affairs Joel Palmer, the tribes were compelled to sign the Treaty with the Tygh and অন্যান্য (Warm Springs) Tribes, 1855, also known as the Treaty of The Dalles.

In this treaty, the tribes ceded approximately 10 million acres of their vast ancestral lands to the United States. In return, they reserved a much smaller tract – approximately 640,000 acres – in Central Oregon, which became the Warm Springs Reservation. Crucially, the treaty explicitly retained their rights to hunt, fish, and gather traditional foods and medicines in their "usual and accustomed places" off the reservation. This provision, though often challenged, would prove vital in future legal battles and cultural preservation efforts.

The early reservation years were fraught with hardship. The diverse tribes, accustomed to distinct territories and lifeways, were suddenly confined to a shared, limited space. Government policies aimed at assimilation often disrupted traditional social structures and cultural practices. Children were sometimes sent to distant boarding schools, where their languages were forbidden, and their cultural identities suppressed. Despite these attempts to dismantle their heritage, the spirit of the people endured. They adapted, forming new inter-tribal connections while striving to maintain their individual identities and traditions.

Forging a Future: Self-Determination and Economic Ingenuity

The 20th century, particularly its latter half, ushered in an era of renewed self-determination and strategic economic development for the Confederated Tribes. Recognizing the need to build a sustainable future on their own terms, the Tribes embarked on ambitious ventures that blended traditional knowledge with modern business acumen.

One of the most significant achievements came in the form of resource management. The vast timber resources on the reservation became the foundation for the Warm Springs Forest Products Industries (WSFPI), established in 1967. This tribal-owned enterprise provided employment, generated revenue, and allowed the Tribes to manage their forests sustainably, a practice rooted in their long-standing respect for the land.

A landmark legal and economic victory arrived in 1964 with the Pelton Dam settlement. The construction of the Pelton and Round Butte hydroelectric dams on the Deschutes River by Portland General Electric (PGE) flooded sacred fishing grounds and altered the river ecosystem within the Tribes’ treaty area. After years of negotiation, the Tribes secured a historic settlement, receiving an initial payment of $4 million and an ongoing share of the power generated. This groundbreaking settlement became a cornerstone of tribal self-sufficiency, funding essential services, infrastructure, and further economic diversification. It allowed the Tribes to invest in their own future, a testament to their foresight and legal tenacity.

The Tribes also ventured into tourism, opening the Kah-Nee-Ta High Desert Resort & Casino in 1972. Kah-Nee-Ta, with its natural hot springs, lodge, and recreational activities, became a celebrated destination, offering a unique blend of cultural experiences and hospitality. Although the resort faced challenges and eventually closed in 2018, its legacy as a symbol of tribal ingenuity and economic ambition remains significant. Today, the Tribes continue to operate the Indian Head Casino, further contributing to their economic independence and ability to fund vital community programs.

Weaving the Threads of Culture and Identity

Amidst the complexities of modern governance and economic development, the preservation of culture remains a paramount endeavor for the Confederated Tribes. Recognizing that language is the soul of a people, significant efforts are dedicated to revitalizing the Kiksht (Wasco), Sahaptin (Warm Springs/Tenino), and Numu (Northern Paiute) languages. Immersion programs, elder mentorships, and educational initiatives strive to pass these vital linguistic traditions to younger generations. "Our language is who we are," states a contemporary tribal leader. "It carries the wisdom of our ancestors, the stories of our land. To lose it is to lose a part of ourselves."

Traditional ceremonies, storytelling, basket weaving, beadwork, and dance are actively practiced and celebrated, ensuring that the rich artistic and spiritual heritage of each constituent tribe continues to flourish. The annual Root Feast and Huckleberry Feast are examples of enduring ceremonies that connect the people to the seasonal cycles of the land and reinforce communal bonds. The elders, revered as keepers of knowledge and tradition, play an indispensable role in educating youth about their history, values, and responsibilities. This intergenerational transfer of knowledge is critical in maintaining a strong sense of identity and continuity.

Contemporary Challenges and Enduring Spirit

Despite these formidable achievements, the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs continue to navigate significant socio-economic challenges. Issues such as high unemployment rates, health disparities, and access to quality education persist. The decline of the timber industry and the closure of Kah-Nee-Ta have necessitated further economic diversification and adaptation. The impact of climate change on traditional food sources, particularly salmon runs, also poses a serious threat to their cultural and economic well-being.

However, the enduring spirit of resilience, deeply ingrained from generations of adapting to change, remains their greatest asset. The Tribes are actively pursuing new ventures in renewable energy, sustainable agriculture, and advanced technology. They are staunch advocates for environmental protection, working tirelessly to restore fish habitat and protect water resources within their treaty territories. Their commitment to sovereignty means actively shaping their own destiny, asserting their rights, and ensuring that their voices are heard on local, state, and national levels.

Looking Ahead: Sovereignty, Sustainability, and the Next Generation

The history of the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs is a powerful narrative of endurance, adaptation, and unwavering cultural pride. From the ancient fishing camps of Celilo Falls to the modern council chambers, their journey reflects a continuous struggle for self-determination and the preservation of a unique way of life. They embody the strength of diverse peoples united by shared values and a common future.

As the Tribes look to the future, their focus remains steadfast on empowering the next generation. Investment in education, youth programs, and leadership development ensures that the legacy of their ancestors—a profound respect for the land, a commitment to community, and an unyielding spirit of resilience—will continue to guide them. The Warm Springs people, like the rivers that flow through their ancestral lands, adapt and persist, their history a vibrant testament to the enduring power of Indigenous identity in Oregon and beyond. Their story is not just a chapter in the history of the Pacific Northwest; it is a living, breathing narrative of a sovereign people actively shaping their destiny, one generation at a time.