A New Dawn on Turtle Island: The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples

On Turtle Island, a continent steeped in the rich histories, cultures, and enduring resilience of its Indigenous peoples, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) stands as a beacon of hope and a blueprint for a more just future. More than a mere document, UNDRIP represents a global consensus on the minimum standards for the survival, dignity, and well-being of Indigenous peoples worldwide. For the First Nations, Inuit, Métis, and Native American tribes across what is now Canada and the United States, its adoption and subsequent endorsements mark a pivotal, albeit complex, turning point in their centuries-long struggle for recognition and self-determination.

For generations, Indigenous peoples on Turtle Island have faced systemic oppression, dispossession of lands, cultural erosion, and the brutal realities of colonialism. From the forced assimilation of residential schools and boarding schools, designed to "kill the Indian in the child," to the broken treaties and ongoing resource extraction on traditional territories without consent, the historical injustices are profound and deeply embedded in the fabric of both nations. The legacy of these policies manifests today in stark socio-economic disparities, health crises, and the continued struggle for inherent rights. UNDRIP emerged from this crucible of injustice, driven by decades of tireless advocacy by Indigenous leaders and human rights champions who brought their lived experiences and demands for justice to the international stage.

Adopted by the UN General Assembly in 2007, UNDRIP is a comprehensive international human rights instrument affirming the collective and individual rights of Indigenous peoples. It establishes a universal framework of minimum standards for the survival, dignity, and well-being of the Indigenous peoples of the world. Notably, four nations with significant Indigenous populations – Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and the United States – initially voted against its adoption. Their eventual endorsements, however, signified a crucial shift in their stated commitments to reconciliation and human rights. For Canada, this came in 2010, and for the United States, in 2010 as well, albeit with reservations. This initial reluctance underscored the profound challenge UNDRIP poses to existing state structures and power dynamics.

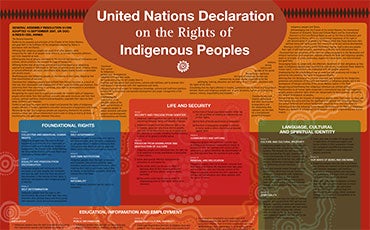

At its heart, UNDRIP is transformative because it recognizes Indigenous peoples not as mere minorities, but as distinct peoples with inherent rights. Central to its philosophy is the principle of self-determination, enshrined in Article 3: "Indigenous peoples have the right to self-determination. By virtue of that right they freely determine their political status and freely pursue their economic, social and cultural development." This is not an aspiration; it is an inherent right, challenging the colonial notion of absolute state sovereignty and demanding recognition of Indigenous nations as distinct political entities. Article 4 further elaborates, stating Indigenous peoples have "the right to maintain and strengthen their distinct political, legal, economic, social and cultural institutions, while retaining their right to participate fully, if they so choose, in the political, economic, social and cultural life of the State."

The most contentious and, arguably, most crucial aspects of UNDRIP on Turtle Island revolve around land, territories, and resources. Article 26 unequivocally states: "Indigenous peoples have the right to the lands, territories and resources which they have traditionally owned, occupied or otherwise used or acquired." It further mandates states to give "legal recognition and protection to these lands, territories and resources." This article directly confronts the historical dispossession and ongoing resource extraction that continues to impact Indigenous communities. Complementing this is Article 32, which mandates states to "consult and cooperate in good faith with the Indigenous peoples concerned through their own representative institutions in order to obtain their free, prior and informed consent (FPIC) before adopting and implementing legislative or administrative measures that may affect them." FPIC is a cornerstone of UNDRIP, demanding Indigenous peoples’ active participation and agreement on any development projects or policies impacting their lands and lives, effectively granting them a veto power that many governments and industries find challenging to accept.

In Canada, the journey towards UNDRIP implementation has been particularly dynamic. After initially voting against the Declaration, Canada officially endorsed it in 2010, followed by a more robust commitment in 2016 when the government announced it would implement UNDRIP "without qualification." This commitment was significantly influenced by the 94 Calls to Action from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC), specifically Call to Action #43, which called on all levels of government to fully adopt and implement UNDRIP as the framework for reconciliation. In June 2021, Canada passed Bill C-15, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act, which legally obligates the federal government to ensure that Canadian laws are consistent with UNDRIP.

This legislative commitment is monumental, yet its practical application presents significant challenges. It necessitates a fundamental re-evaluation of federal, provincial, and territorial laws, policies, and operational frameworks. Debates around FPIC, for instance, have become central to major resource projects, from pipelines like Coastal GasLink through Wet’suwet’en territory to hydroelectric dams and mining operations. Indigenous communities, emboldened by UNDRIP, are increasingly asserting their right to say "no" or to negotiate equitable partnerships. The Tsilhqot’in Nation’s landmark 2014 Supreme Court of Canada decision, affirming Aboriginal title to a specific tract of land, though predating Bill C-15, exemplifies the spirit of UNDRIP and sets a powerful precedent for land rights recognition in Canada. The ongoing work involves intricate negotiations, legal challenges, and a shift in mindset from paternalism to genuine partnership, requiring immense political will and public education.

South of the border, the United States’ approach to UNDRIP has been more cautious. While the Obama administration announced its support for UNDRIP in 2010, it did so with a qualifying statement, emphasizing that the Declaration "does not require changes to existing federal law or the U.S. Constitution." This stance reflects a persistent tension between international human rights standards and domestic legal frameworks, particularly concerning tribal sovereignty and land rights. Despite this, UNDRIP has become an increasingly powerful advocacy tool for Native American tribes and organizations within the U.S. legal and political landscape.

Issues such as the protection of sacred sites, the rights of access to traditional territories, and the battle against resource extraction projects serve as battlegrounds where UNDRIP principles are invoked. The struggle against the Dakota Access Pipeline at Standing Rock, for example, brought the concept of FPIC and the right to protect cultural heritage (Article 11) into sharp focus on a global stage. Similarly, the ongoing fight to protect places like Bears Ears National Monument or Oak Flat from mining operations highlights the persistent challenge of reconciling economic interests with Indigenous rights to land and culture. Tribal governments in the U.S. continue to assert their inherent sovereignty, operating tribal courts, police forces, and healthcare systems, often citing UNDRIP as an international affirmation of these inherent rights, even if the U.S. federal government maintains a more nuanced interpretation of its direct legal applicability.

Beyond self-determination and land, UNDRIP is also crucial for the revitalization of Indigenous languages, cultures, and knowledge systems. Articles 11, 12, 13, and 14 affirm the right to practice and revitalize cultural traditions, use and teach their languages, and establish their own educational systems. On Turtle Island, where generations of Indigenous children were punished for speaking their languages in residential and boarding schools, these articles provide a powerful framework for healing and cultural resurgence. Communities are leveraging UNDRIP to advocate for increased funding for language immersion programs, the repatriation of cultural artifacts, and the incorporation of traditional knowledge into contemporary governance and environmental stewardship.

The implementation of UNDRIP on Turtle Island is not merely a legal exercise; it is a profound societal transformation. It demands a reckoning with history, a commitment to justice, and a willingness to forge new relationships based on respect, equality, and partnership. While significant obstacles remain – including resistance from industries, political expediency, and deeply ingrained prejudices – the Declaration provides a roadmap for moving beyond colonial legacies towards genuine reconciliation. It empowers Indigenous peoples with an internationally recognized standard to assert their rights, ensuring that their voices are heard and their inherent sovereignty is respected. As nations on Turtle Island continue their journey towards reconciliation, UNDRIP remains a vital, living document, guiding the path to a future where Indigenous peoples not only survive but thrive, determining their own destinies on their ancestral lands. The dawn of this new era is still breaking, but the light of UNDRIP shines brightly, illuminating the way forward.