Sovereignty and Scars: The Enduring Saga of Tribal-Federal Relations in the United States

The relationship between the United States federal government and the sovereign tribal nations within its borders is a tapestry woven with threads of broken promises, profound resilience, and an ongoing struggle for self-determination. It is a relationship unlike any other the U.S. maintains, born from treaties, shaped by conquest and policy shifts, and defined today by concepts of inherent sovereignty, a federal trust responsibility, and the aspiration of nation-to-nation diplomacy. Far from a relic of the past, this dynamic and often fraught relationship continues to evolve, impacting land, resources, justice, and the very identity of nearly 600 federally recognized tribes and the millions of Indigenous people they represent.

To understand the present, one must confront the past. For millennia before European contact, hundreds of distinct Indigenous nations thrived across North America, governing themselves with complex political, social, and economic systems. Early interactions with European powers, and subsequently the nascent United States, often began with treaty-making – a recognition of tribal nations as sovereign entities capable of entering into international agreements. These treaties, some 370 ratified between 1778 and 1871, typically involved tribal cessions of vast territories in exchange for assurances of perpetual peace, protection, and the right to retain remaining lands and resources.

However, the ink on these agreements often dried before the promises they contained evaporated. As the U.S. expanded westward, its policies toward Native Americans shifted from diplomacy to displacement. The infamous Indian Removal Act of 1830 led to the forced relocation of countless tribes, most notably the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole nations from their ancestral lands in the southeastern U.S. to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma) during the "Trail of Tears." Thousands perished from disease, starvation, and exposure. This period underscored a fundamental tension: while the Supreme Court in Worcester v. Georgia (1832) affirmed tribal nations as "distinct political communities, having territorial boundaries, within which their authority is exclusive," the federal government often chose to ignore such rulings in favor of land hunger and Manifest Destiny.

The late 19th and early 20th centuries saw the federal government embark on an aggressive assimilation policy aimed at dismantling tribal cultures and governments. The Dawes Act of 1887, or General Allotment Act, broke up communally held tribal lands into individual parcels, with "surplus" lands sold off to non-Native settlers. This policy resulted in the loss of nearly two-thirds of the remaining tribal land base – approximately 90 million acres – between 1887 and 1934, profoundly disrupting traditional social structures and economic practices. Concurrently, children were forcibly removed from their families and sent to boarding schools, where they were forbidden to speak their native languages or practice their cultures, under the guise of "killing the Indian to save the man."

A significant shift occurred with the Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) of 1934, which ended allotment, encouraged tribal self-governance through constitutional reform, and provided some economic development support. While imperfect and still paternalistic in its implementation, the IRA marked a departure from the destructive assimilation policies. Yet, the pendulum swung again in the 1950s with the "Termination Era," a disastrous policy aimed at severing the federal government’s relationship with tribes and dissolving tribal governments. Over 100 tribes were terminated, losing their federal recognition, trust lands, and treaty rights, plunging many into extreme poverty and despair.

The catastrophic failures of termination ultimately paved the way for the modern era of "Self-Determination." Beginning in the 1970s, with landmark legislation like the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975, the federal government began to affirm tribal sovereignty and support tribal control over their own affairs. This era recognized that the most effective way to address the myriad challenges facing Native communities was to empower tribal nations to govern themselves and design their own programs and services.

Today, the relationship rests on several fundamental pillars. Foremost is tribal sovereignty: the inherent right of tribal nations to govern themselves. This sovereignty predates the United States and is not granted by the federal government, but rather recognized by it. As President Biden affirmed in 2021, the U.S. has a "unique nation-to-nation relationship with Tribal Nations," acknowledging their distinct governmental status.

Alongside sovereignty is the federal trust responsibility. This legal and moral obligation stems from treaties and federal statutes, requiring the U.S. government to protect tribal lands, assets, resources, and self-governance. It mandates that the federal government act as a fiduciary for tribal nations, a role often likened to that of a trustee for a beneficiary. This responsibility underpins federal funding for vital services such as healthcare (through the Indian Health Service), education, housing, and infrastructure, though these services are notoriously underfunded compared to need. For instance, the Indian Health Service consistently operates at a fraction of the funding levels recommended to meet the health needs of Native populations.

Despite the rhetoric of "nation-to-nation," the relationship is not one of equals in all respects. The U.S. Congress retains "plenary power" over Indian affairs, meaning it can unilaterally legislate regarding tribes, sometimes overriding tribal self-governance. This power, while tempered by judicial review and political considerations, remains a significant tension point, reminding tribes of the precariousness of their recognized sovereignty.

Contemporary Tribal-Federal relations are characterized by a complex array of issues and ongoing challenges. Economic development is a prime example. The Indian Gaming Regulatory Act (IGRA) of 1988 allowed tribes to operate casinos, transforming the economic landscape for many. Tribal gaming generates tens of billions of dollars annually, creating jobs and funding essential tribal government services that would otherwise be unfunded by the federal government. Yet, not all tribes have lands suitable for gaming or are geographically positioned to benefit, and many still face significant economic disparities. Beyond gaming, tribes are increasingly diversifying their economies through tourism, natural resource management, manufacturing, and technology, leveraging their sovereign status to attract investment and create sustainable futures.

Land and water rights remain critical and often contentious issues. Many tribes are still fighting for the return of ancestral lands, for adequate water allocations crucial for agriculture and sustenance, and for protection of sacred sites. The federal government’s role as trustee for tribal lands often puts it in the position of balancing tribal interests with those of neighboring states, industries, and non-Native populations, leading to protracted legal battles.

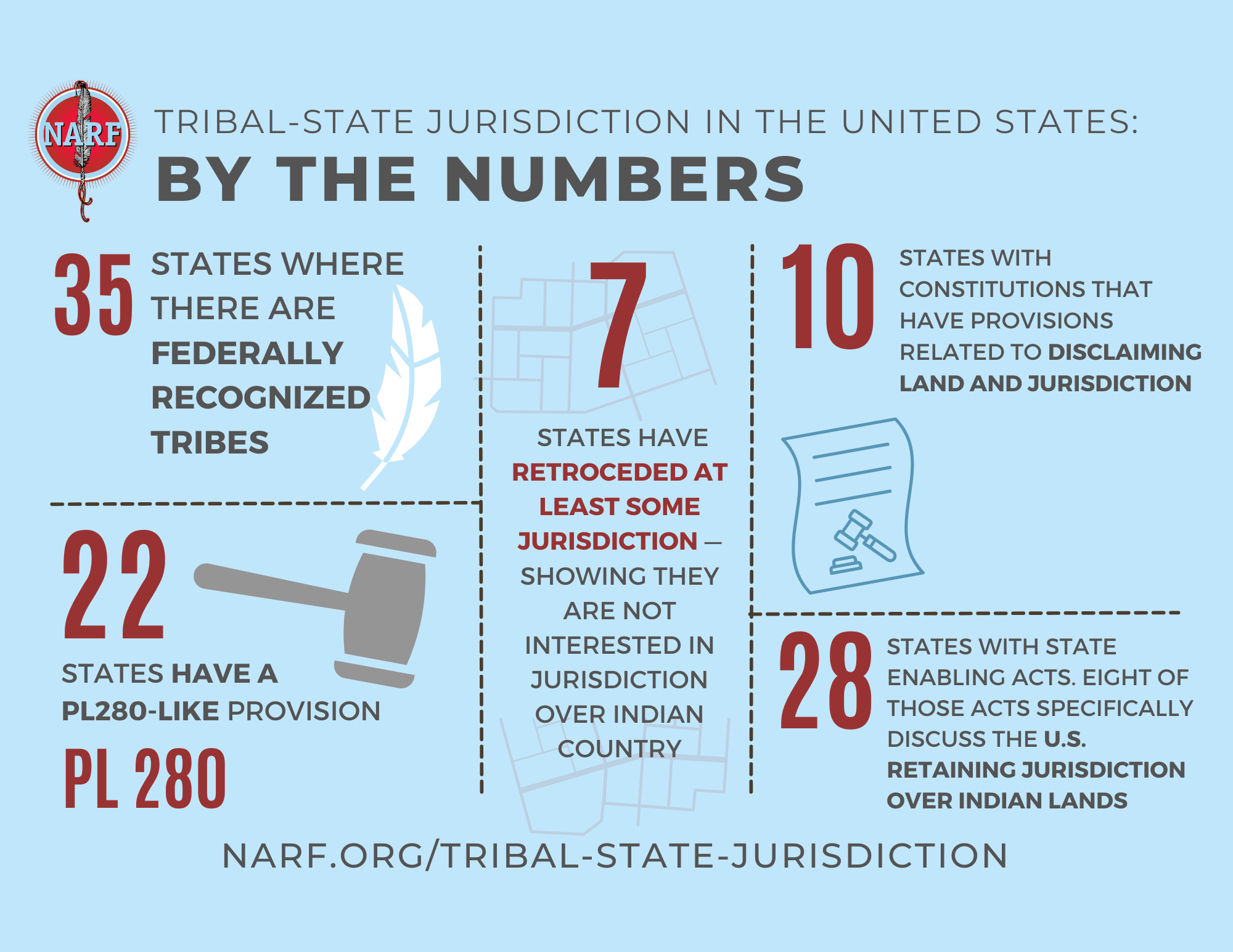

Jurisdiction over law enforcement and justice is another deeply complex area. The patchwork of federal, state, and tribal laws creates significant gaps, particularly on reservations. This complexity is tragically evident in the crisis of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG), where jurisdictional ambiguities and lack of resources often impede investigations, contributing to alarmingly high rates of violence against Native women. While legislation like the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) has been expanded to allow tribal courts greater authority over non-Native perpetrators in certain domestic violence cases, significant gaps persist, especially for crimes committed by non-Natives against Natives on tribal lands.

Environmental protection and resource management are also central. Tribal nations often hold deep traditional ecological knowledge and are at the forefront of climate change impacts. They frequently engage with federal agencies on issues ranging from pipeline approvals to protected area designations, advocating for environmental justice and the protection of ancestral lands and waters. The federal government’s duty to consult with tribes on projects impacting their lands and resources is a crucial, though sometimes inconsistently applied, aspect of this relationship.

Despite these challenges, the narrative of Tribal-Federal relations is far from one of unmitigated struggle. There are increasing examples of successful partnerships and progress. Tribes are asserting their sovereignty with greater effectiveness, building robust governmental structures, developing their economies, and revitalizing their cultures and languages. Tribal leaders are powerful advocates in Washington D.C., influencing policy and legislation. Federal agencies are, with varying degrees of success, improving their consultation processes with tribes, aiming for more meaningful engagement rather than mere notification. Initiatives like co-management agreements for national parks and forests, and the return of some ancestral lands, signal a growing recognition of tribal nations’ expertise and inherent rights.

In conclusion, the relationship between the U.S. federal government and tribal nations is a living, evolving entity, scarred by history but imbued with the profound resilience of Indigenous peoples. It is a testament to the enduring sovereignty of tribal nations and the federal government’s constitutional and moral obligations. While the journey towards true nation-to-nation partnership, marked by mutual respect and equity, is ongoing, the increasing emphasis on self-determination and the growing visibility of Indigenous voices offer hope. For the United States, understanding and honoring this unique relationship is not merely a matter of historical reckoning, but a fundamental commitment to justice, equity, and the promise of a more inclusive future for all its citizens.