When Indigenous Voices Shook the Capital: The Trail of Broken Treaties and the Quest for Justice

In the autumn of 1972, a powerful, symbolic caravan of automobiles, buses, and trucks snaked its way across the North American continent, a modern-day pilgrimage with a profound purpose. Bearing the poignant moniker "The Trail of Broken Treaties," this cross-country journey, spearheaded by the American Indian Movement (AIM) and various tribal organizations, culminated in a week-long occupation of the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) headquarters in Washington D.C. It was a potent, dramatic protest, born of centuries of injustice, demanding the federal government honor its sacred obligations and redefine its relationship with Indigenous nations.

The event etched itself into the annals of American history as a pivotal moment in the Indigenous rights movement, a defiant cry for sovereignty and self-determination that resonated far beyond the barricaded doors of the BIA building. It was a visible, undeniable manifestation of the "Red Power" movement, asserting Indigenous identity and demanding a reckoning with a colonial past.

A Legacy of Betrayal: The Genesis of the Protest

For generations, Indigenous peoples in the United States had endured a relentless assault on their sovereignty, culture, and lands. From the earliest colonial encounters, a pattern of treaty-making followed by systemic abrogation became the norm. The 19th century saw forced removals like the Cherokee’s "Trail of Tears," the bloody Indian Wars, and the reservation system designed to isolate and control. Policies such as the Dawes Act of 1887 fragmented communal lands, while the later "Termination Era" of the 1950s and 60s sought to dissolve tribal governments and assimilate Indigenous peoples into mainstream society, often with devastating economic and cultural consequences.

The federal agency ostensibly created to protect Indigenous interests, the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), was often perceived by Native communities as an instrument of assimilation and control, rather than advocacy. Housed in a formidable building in the nation’s capital, it became a symbol of federal paternalism and bureaucratic indifference, earning it the ironic moniker "Fort Apache" among some activists.

Against this backdrop of historical grievance and ongoing oppression, the American Indian Movement emerged in the late 1960s, a militant and highly visible organization advocating for Indigenous rights, religious freedom, and an end to police brutality. AIM, alongside other tribal groups, understood that traditional political channels had largely failed to address their concerns. A more direct, confrontational approach was needed to capture national attention and force a dialogue.

The Caravan: A Modern-Day Pilgrimage

The idea for the "Trail of Broken Treaties" originated with Native activists who sought a direct confrontation with the federal apparatus in Washington D.C. Organized by the Native American Rights Fund (NARF) and led by prominent figures like Russell Means, Dennis Banks, and Carter Camp of AIM, the caravan began its journey from diverse points across the country in late October 1972. Participants, representing over 250 Indigenous nations, converged on the nation’s capital, literally following the "trail" of broken promises that stretched from coast to coast.

The journey itself was a powerful statement. It was a symbolic reversal of the forced marches of their ancestors, a collective act of reclamation and resilience. Along the way, the caravan stopped in various cities, holding rallies, educating the public about their plight, and gathering momentum. The sheer logistical effort of organizing hundreds of people and vehicles, often with limited resources, underscored the deep commitment and determination of the participants. Their destination was not merely Washington D.C.; it was the heart of the government that had consistently failed them.

Arrival and Occupation: "Fort Apache" Under Siege

Upon their arrival in Washington D.C. on November 1, the activists, numbering around 500-1000, expected to meet with government officials regarding their grievances. However, logistical failures, including a lack of promised accommodations and a perceived dismissive attitude from BIA officials, quickly soured the atmosphere. What began as an intended peaceful protest and dialogue rapidly escalated.

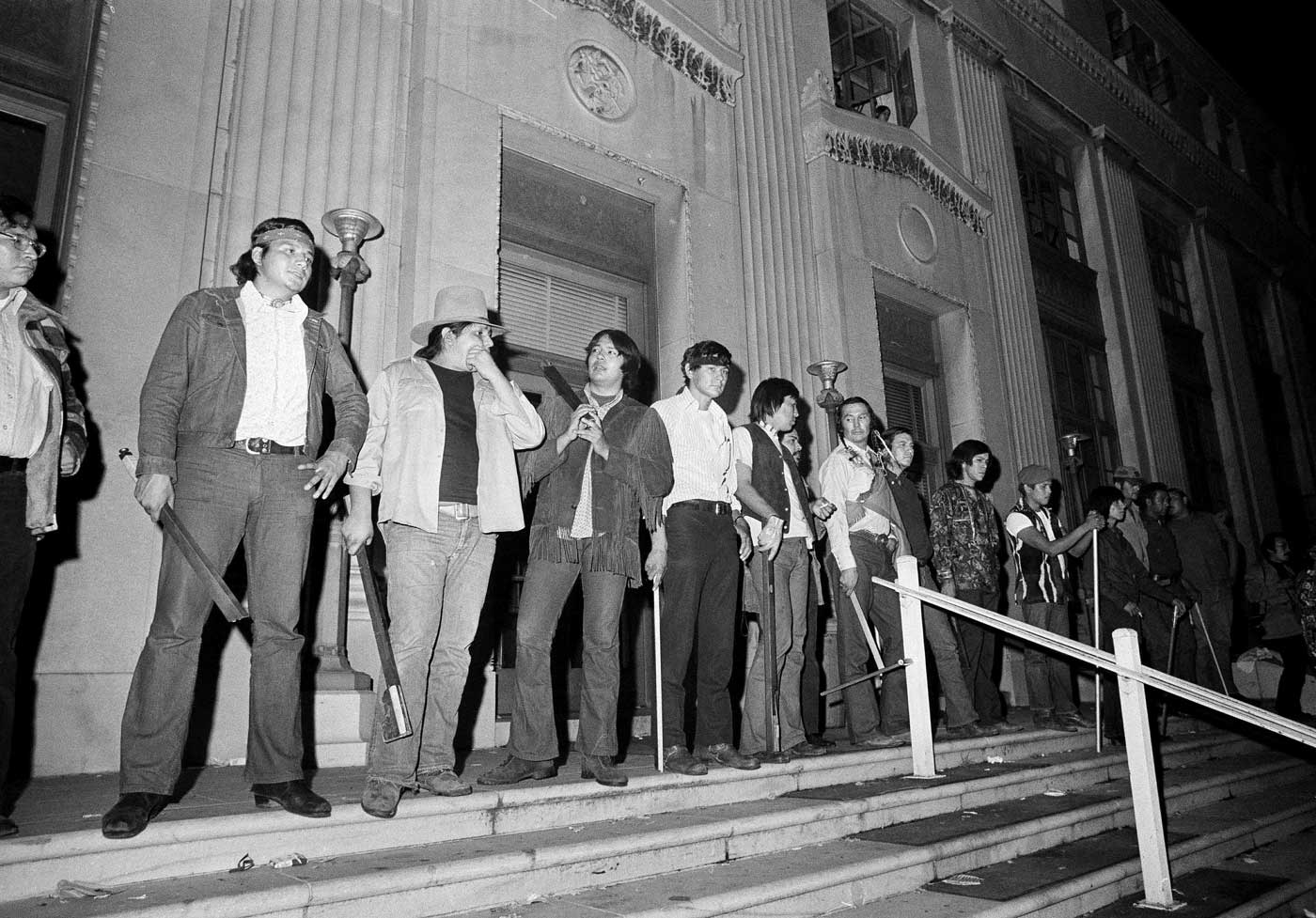

On November 2, the situation boiled over. Frustrated by the lack of respect and the government’s apparent disinterest, a group of activists entered the BIA building and, in a spontaneous act of defiance, decided to occupy it. The initial takeover quickly solidified into a full-blown occupation. Barricades were erected using furniture, offices were transformed into living quarters, and the building’s exterior was adorned with banners proclaiming "AIM" and "Custer Died for Your Sins," along with a large, inverted American flag – a traditional sign of distress.

For seven days, from November 2 to November 9, the BIA building became a fortified symbol of Indigenous resistance. The occupation was both a physical and a symbolic act. By taking over the very institution meant to administer their lives, the activists were asserting their right to self-governance and challenging the legitimacy of the BIA’s authority.

The Twenty Points: A Blueprint for Self-Determination

At the heart of the protest lay a document known as the "Twenty Points," a comprehensive set of demands outlining fundamental reforms to federal Indian policy. These points represented a radical departure from the prevailing paternalistic approach, advocating for Indigenous self-determination and the restoration of treaty rights.

Among the most significant demands were:

- Abolition of the BIA: Point 3 called for the complete dismantling of the BIA, which activists viewed as an oppressive colonial institution, and its replacement with a new "Office of Federal Indian Relations and Community Reconstruction" directly accountable to Indigenous communities.

- Restoration of Treaty-Making Status: Point 10 demanded the restoration of the constitutional treaty-making authority with Indigenous nations, recognizing them as sovereign entities.

- Review of Treaty Violations: Point 1 called for the review of all treaties between Indigenous nations and the U.S. government, with a commitment to their enforcement.

- Land Reform and Restoration: Several points addressed land issues, including the restoration of Indigenous lands unlawfully taken and the recognition of Indigenous water rights.

- Protection of Religious and Cultural Freedoms: Demands included the protection of Native religions and cultures, often suppressed by federal policies.

- Improved Health, Housing, and Education: The document also called for substantial improvements in federal funding and programs for Indigenous communities, addressing chronic disparities in health, housing, and education.

The "Twenty Points" was more than a list of grievances; it was a comprehensive blueprint for a new relationship between the U.S. government and Indigenous nations, based on respect, sovereignty, and self-determination. As Russell Means, a prominent AIM leader, famously declared, "We are not protesting; we are liberating. We are here to reclaim what is ours."

The Standoff and Controversies

The occupation created a tense standoff with federal authorities. Law enforcement surrounded the building, and negotiations began, led by figures such as Assistant Secretary of the Interior Harrison Loesch and later by White House aides. Media coverage was extensive, bringing the plight of Indigenous peoples to national and international attention, albeit often with a focus on the dramatic aspects of the occupation.

The occupation was not without its controversies. Reports of significant damage to the BIA building, estimated at over $2 million (equivalent to more than $14 million today), and the alleged theft or destruction of thousands of sensitive government documents, drew sharp criticism from the government and some segments of the public. Activists countered that the damage was largely incidental to their need to secure the building and that many of the "stolen" documents were, in fact, copies of treaties and historical records that rightfully belonged to Indigenous nations, or evidence of BIA corruption they intended to expose. They argued that the true cost of the protest was negligible compared to the centuries of wealth extracted from Indigenous lands and the systemic destruction of their cultures.

Resolution and Aftermath

As the standoff wore on, negotiations intensified. Eventually, a resolution was brokered, largely facilitated by sympathetic individuals within the government and tribal leaders. The Nixon administration, keen to avoid further escalation and negative publicity, agreed to appoint a task force to review the "Twenty Points" and provide funds for the activists’ safe return home. On November 9, 1972, the occupation ended peacefully, with the activists departing the BIA building and returning to their communities.

In the immediate aftermath, the promises made by the government largely evaporated. The task force proved ineffective, and few of the "Twenty Points" were ever formally adopted. Federal authorities launched investigations into the damage and missing documents, leading to indictments and further strained relations. The government’s response was largely dismissive of the substantive demands, focusing instead on the perceived lawlessness of the protest.

The Enduring Legacy: A Catalyst for Change

Despite the government’s initial failure to act on the demands, the Trail of Broken Treaties profoundly impacted the trajectory of Indigenous rights in the United States. It thrust Native American issues into the national spotlight with unprecedented force, forcing mainstream America to confront the uncomfortable realities of its history and ongoing injustices.

The protest galvanized the budding self-determination movement, serving as a powerful precursor to other significant Indigenous actions, most notably the Wounded Knee Occupation of 1973. It demonstrated the power of direct action and inspired a new generation of Indigenous leaders and activists.

Crucially, while the "Twenty Points" were not immediately enacted, the spirit of their demands eventually influenced subsequent federal policy. The Nixon administration, despite its initial reaction, had already begun to shift towards a policy of "self-determination without termination," a move away from the assimilationist policies of the past. The Trail of Broken Treaties undoubtedly accelerated this shift, creating a political climate where the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975, a landmark piece of legislation that dramatically increased tribal control over federal programs and resources, could be passed.

The Trail of Broken Treaties remains a pivotal moment in the history of Indigenous activism – a testament to the enduring power of protest in the face of centuries of systemic injustice. It was a raw, defiant cry for recognition, sovereignty, and the simple honor of promises made. It reminded the nation that Indigenous peoples were not a relic of the past, but a vibrant, resilient force demanding their rightful place in the present and future. The echoes of those broken treaties still resonate, but so too does the unwavering call for justice first sounded so forcefully in the autumn of 1972.