The Sacred Harvest: Traditional Ojibwe Wild Rice Harvesting – Cultural Significance and Sustainable Practices

For the Anishinaabeg people of the Great Lakes region, particularly the Ojibwe, wild rice is far more than a staple food; it is a spiritual cornerstone, a testament to ancient prophecies, and a living embodiment of their enduring connection to the land and water. Known as Manoomin (the good berry) in Ojibwemowin, this grain has sustained communities for millennia, its harvesting practices meticulously refined over generations to ensure both bounty and ecological harmony. In an era marked by environmental degradation and the erosion of traditional knowledge, the Ojibwe’s continued dedication to Manoomin harvesting stands as a powerful lesson in cultural resilience and sustainable stewardship.

The story of Manoomin begins with the Great Migration prophecy, which foretold the Anishinaabeg’s journey westward from the Atlantic coast until they found "the food that grows on water." This prophecy led them to the vast network of lakes and rivers in what is now Minnesota, Wisconsin, Michigan, and Ontario, where wild rice beds flourished. Upon discovering Manoomin, the prophecy was fulfilled, solidifying the grain’s sacred status. It became a central pillar of their diet, providing essential nutrients through harsh winters, and a vital component of ceremonies, feasts, and trade. To the Ojibwe, Manoomin is a gift from the Creator, a living entity that demands respect, reciprocity, and protection.

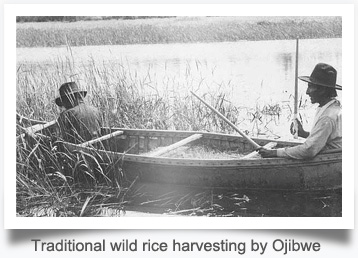

The harvesting of Manoomin is an intricate dance with nature, guided by deep ecological knowledge and a profound sense of responsibility. Unlike modern industrial agriculture, traditional Ojibwe methods are inherently sustainable, designed to nurture the wild rice beds rather than exploit them. The season typically begins in late August and extends into early September, when the rice grains are mature but not yet fallen. Harvesters venture onto the lakes in shallow-draft canoes, traditionally made of birch bark, though aluminum canoes are common today. A pair of harvesters works in tandem: one paddles or poles the canoe gently through the dense rice beds, while the other uses two smooth, wooden knocking sticks, known as maanaagan.

The technique is deceptively simple but requires immense skill and patience. With one stick, the harvester bends a clump of rice stalks over the canoe. With the second stick, they gently tap the heads of the stalks, knocking the ripe grains into the bottom of the canoe. Only the mature grains fall, while unripe kernels remain on the plant, ensuring future yields and allowing for multiple passes over the same bed throughout the season. This method is remarkably gentle, causing minimal disturbance to the plants, the lakebed, or the surrounding ecosystem. It also leaves ample grains for reseeding and for the myriad waterfowl and other wildlife that depend on Manoomin as a food source. This inherent respect for the plant’s life cycle and the broader ecosystem is a cornerstone of Ojibwe sustainable practices.

"It’s not just about getting food; it’s about connecting with creation, with our ancestors," explains Joe Nayquonabe Jr., a Fond du Lac Ojibwe cultural preservation specialist. "When you’re out there, you’re not just harvesting rice; you’re harvesting tradition, language, and identity. You’re giving thanks." This spiritual dimension underscores every aspect of the harvest, from the "first fruits" ceremony that often precedes the season to the shared labor and communal feasting that follows.

Once harvested, the Manoomin undergoes a multi-stage traditional processing that further distinguishes it from commercially cultivated varieties. This process, often a community effort, involves several critical steps:

- Drying (Parching): The green wild rice is first dried to reduce moisture content. Historically, this involved sun-drying on mats or parching over a slow fire in large iron kettles. Parching over fire imparts a distinct, smoky flavor and helps separate the kernel from its hull.

- Threshing (Jigging): The dried rice is then "jigged" to remove the outer hull. Traditionally, this was done by placing the rice in a shallow pit lined with canvas or hide and treading on it with moccasin-clad feet. The "dancing" motion separates the hull without crushing the delicate grain. Today, some communities use mechanical threshers that mimic this gentle action.

- Winnowing: Finally, the threshed rice is winnowed to separate the lighter chaff from the heavier, clean grains. This is typically done by tossing the rice in a large birch bark winnowing tray (nooshkaachinaagan) on a breezy day, allowing the wind to carry away the chaff.

The result is a dark, slender grain with a rich, nutty flavor and chewy texture, vastly different from the pale, plump, and often bland "wild rice" found in supermarkets, which is typically cultivated in flooded paddies using machinery and hybridized seeds. This traditional processing not only preserves the grain’s unique characteristics but also ensures its longevity, making it a valuable food source for months or even years.

The sustainability of traditional Ojibwe harvesting is not merely incidental; it is a core tenet of their worldview. Their methods ensure the perpetuation of the wild rice beds, reflecting a long-term perspective that prioritizes future generations. This contrasts sharply with many modern agricultural practices that prioritize short-term yield over ecological health. The Ojibwe understand the delicate balance of the ecosystems in which Manoomin thrives, recognizing the interconnectedness of water quality, wildlife, and plant health. They act as stewards, not simply harvesters.

However, the revered Manoomin faces unprecedented threats. Environmental degradation is perhaps the most significant challenge. Pollution from industrial and agricultural runoff, changes in water levels due to dams and climate change, and the proliferation of invasive species like carp (which uproot wild rice plants) and purple loosestrife (which outcompetes native vegetation) are decimating traditional rice beds. Industrial development, particularly mining and oil pipelines, poses direct threats to the pristine watersheds that nourish Manoomin. For instance, the proposed Enbridge Line 3 pipeline expansion through northern Minnesota raised significant concerns among Ojibwe tribes due to its potential impact on critical wild rice lakes and wetlands.

Furthermore, the legal status and access to traditional harvesting grounds are constantly under threat. Treaties guarantee Ojibwe usufructuary rights (the right to use and enjoy the fruits and profits of another’s property), including the right to hunt, fish, and gather on ceded territories. Yet, these rights are frequently challenged or undermined by state regulations and private land ownership, forcing communities to continuously defend their access to vital resources.

In response to these threats, Ojibwe communities are engaged in vigorous revitalization efforts. Projects to restore damaged rice beds, community-led monitoring programs, and educational initiatives aimed at teaching younger generations the traditional practices and language associated with Manoomin are flourishing. Organizations like the Great Lakes Indian Fish and Wildlife Commission (GLIFWC) play a crucial role in advocating for tribal rights, conducting research, and collaborating with state and federal agencies to protect Manoomin habitats.

Some tribes are exploring innovative legal strategies, such as the "Rights of Nature" movement, to grant legal personhood to Manoomin itself, allowing it to be represented in court against threats. The White Earth Nation, for example, passed a tribal law recognizing the inherent rights of Manoomin to exist, flourish, and naturally evolve, and the right to restoration, recovery, and preservation. This bold move underscores the depth of their commitment and their determination to protect this sacred plant by any means necessary.

"Protecting Manoomin isn’t just about protecting a food source; it’s about protecting our identity, our culture, our future," says an Ojibwe Elder. "If Manoomin disappears, a part of us disappears with it."

The journey of Manoomin from ancient prophecy to modern-day ecological battleground is a compelling narrative of survival, resilience, and profound cultural significance. The traditional Ojibwe methods of harvesting wild rice are not merely antiquated practices; they are living blueprints for sustainable living, offering invaluable lessons for a world grappling with environmental crises. By honoring the wisdom embedded in their ancestral ways, the Ojibwe continue to uphold their sacred responsibility as guardians of Manoomin, ensuring that the "food that grows on water" will continue to nourish their bodies, spirits, and culture for generations to come. Their fight is a universal call to recognize the intrinsic value of nature and the indispensable role of Indigenous knowledge in fostering a truly sustainable future.