The Shield and The Wisdom: Unpacking Traditional Military Leadership in Tribal Structures

In a world increasingly defined by hierarchical military structures, formal academies, and sophisticated command chains, the concept of military leadership often conjures images of starched uniforms, strategic war rooms, and a clear distinction between officer and enlisted. Yet, long before the advent of modern nation-states and their standing armies, humanity’s earliest forms of organized defense and offense were forged within the intricate social tapestries of tribal societies. Here, military leadership was not merely a profession but an intrinsic aspect of community survival, deeply interwoven with social, spiritual, and political roles. It was a leadership born of necessity, proven in action, and sustained by the respect and trust of the people it served.

To understand traditional military leadership in tribal structures is to look beyond the battlefield and into the very heart of the community. Unlike the specialized military branches of today, a tribal war leader was rarely just a soldier. They were often elders, hunters, spiritual guides, and diplomats – figures whose authority stemmed not from an appointed rank but from a demonstrated capacity to protect, provide, and guide their people through perilous times. This article delves into the multi-faceted nature of these roles, exploring their selection, responsibilities, strategic acumen, and the profound lessons they offer about leadership itself.

The Crucible of Necessity: Selection and Legitimacy

The genesis of military leadership in tribal societies was inherently pragmatic. Survival in often harsh and contested environments demanded effective defense against rival tribes, predatory animals, and resource scarcity. Consequently, leaders were not chosen by birthright alone, nor were they appointed by a distant authority. Their legitimacy was earned through a rigorous, often unspoken, process of observation and trial.

Courage in battle was paramount, but it was rarely sufficient. A true leader had to possess strategic foresight, an intimate knowledge of the terrain, exceptional hunting and tracking skills, and the wisdom to make decisions that balanced the immediate needs of war with the long-term well-being of the community. As the Lakota people understood, a good leader (or Itancan) was not just brave but also generous, wise in counsel, and a provider for his people. The renowned Lakota chief, Sitting Bull, epitomized this, his influence stemming from his prowess as a warrior, his spiritual visions, and his unwavering dedication to his people.

"Among us, the ‘warrior’ is a protector, a provider, not merely a fighter," says Dr. John Mohawk, a Seneca scholar, emphasizing the holistic nature of the role. "He is chosen for his proven ability to ensure the community’s survival, not just to win battles." This highlights a crucial distinction: modern military leadership often focuses on achieving objectives within a defined campaign, whereas tribal military leadership was inextricably linked to the continuous struggle for the community’s existence.

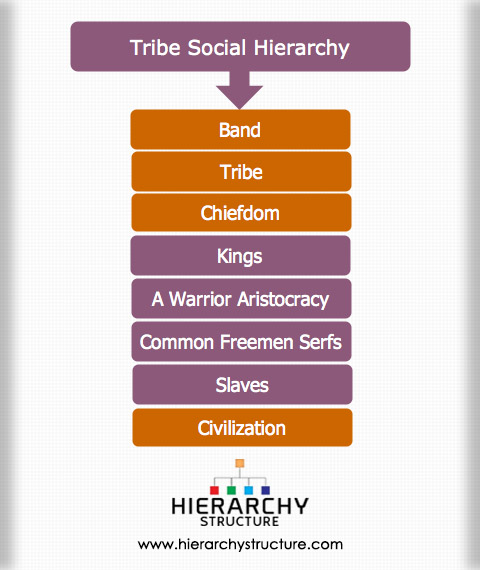

Selection processes varied widely across tribes. Among many Native American nations, for instance, a war chief might be chosen by a council of elders based on their track record in raiding, defense, and their ability to inspire confidence. Among the Māori of New Zealand, leadership (rangatiratanga) was often hereditary but had to be validated through deeds, including martial prowess and the ability to lead the taua (war party) effectively. A chief who failed to protect his people or lead them successfully could quickly lose mana (prestige and authority).

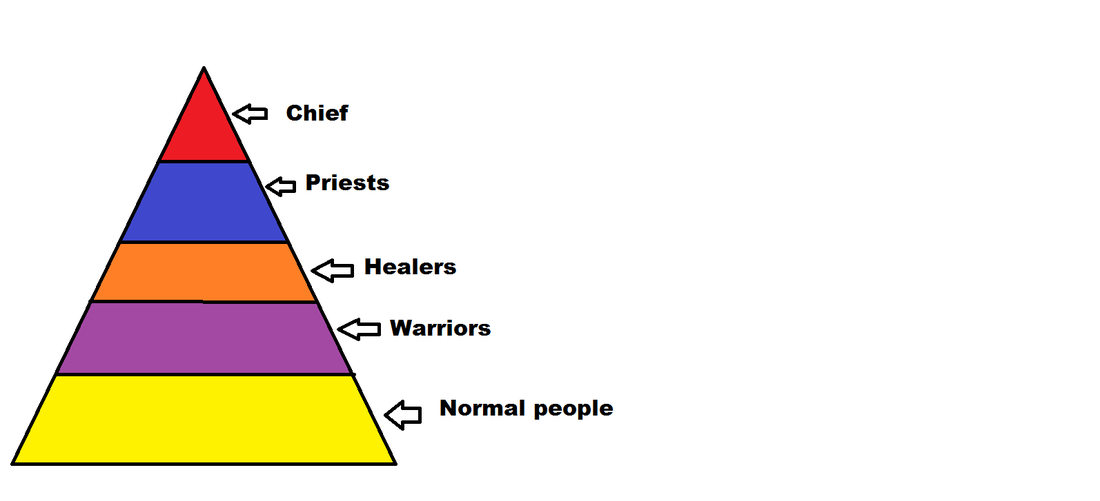

The Holistic Commander: Intertwined Roles

One of the most striking aspects of traditional tribal military leadership is the near-seamless integration of military duties with social, political, and even spiritual responsibilities. A war leader was often also a key figure in the tribal council, a respected elder, and sometimes a spiritual guide or shaman. This meant that decisions regarding conflict were rarely purely tactical; they were deeply embedded in the wider cultural and moral framework of the tribe.

Consider the Apache, whose legendary guerrilla warfare tactics allowed small bands to evade and outmaneuver vastly superior forces for decades. Leaders like Geronimo and Cochise were not just military strategists; they were also spiritual figures, family men, and fierce defenders of their ancestral lands and way of life. Their understanding of the land, its spirits, and its resources was as crucial to their military success as their tactical brilliance. Geronimo, for instance, often consulted with spiritual visions before embarking on campaigns, seeing the spiritual and material worlds as fundamentally connected in the struggle for survival.

This holistic approach meant that military campaigns were not abstract exercises of power but deeply personal undertakings, directly impacting the leader’s family, friends, and entire community. This fostered a profound sense of accountability. A leader’s failure in battle could mean not just personal defeat but the loss of loved ones, ancestral lands, and the very fabric of their society. This intense personal stake often led to a more cautious, deliberate, and deeply empathetic style of leadership, where the lives of every warrior were valued not just as resources but as integral members of the kinship network.

Strategy from the Land: Tactical Genius and Environmental Mastery

Tribal military leaders were masters of their environment. Their strategies were not drawn from textbooks but from generations of accumulated knowledge about local topography, weather patterns, animal behavior, and the habits of their adversaries. This intimate connection to the land transformed the environment itself into a strategic asset.

- Guerrilla Warfare: Many tribal groups, particularly in the Americas, Africa, and parts of Asia, perfected guerrilla tactics long before the term was coined. The ability to launch swift, decisive raids and then vanish into the wilderness, utilizing natural cover and intricate knowledge of escape routes, was a hallmark of their military genius. The Comanche, for example, were renowned for their horseback riding skills and lightning-fast raids across the plains, making them a formidable force.

- Intelligence Gathering: Scouting and reconnaissance were critical. Leaders relied on skilled trackers and scouts to gather information on enemy movements, numbers, and intentions. This intelligence was often derived from subtle signs in nature – disturbed earth, broken branches, the behavior of birds – interpreted by individuals with a profound connection to their surroundings.

- Adaptability: Tribal warfare was highly adaptive. Leaders had to be able to change plans on the fly, responding to unexpected developments with agility and resourcefulness. This contrasted sharply with the often rigid, top-down command structures of invading colonial forces.

- Logistics and Sustainability: While not formalized as in modern armies, logistics were managed through hunting, foraging, and the ability to live off the land. This self-sufficiency allowed for sustained campaigns without the need for extensive supply lines, a significant advantage in protracted conflicts.

As Chief Tecumseh, the Shawnee leader, demonstrated, even when faced with technologically superior forces, a deep understanding of strategy and unity could present a formidable challenge. His efforts to unite various Native American tribes against American expansion showcased a sophisticated political and military mind, rooted in traditional leadership principles but adapted to a new, existential threat.

The Legacy of Leadership: Lessons for Today

The roles of traditional military leaders in tribal structures, while seemingly distant from contemporary defense paradigms, offer profound lessons that remain relevant today.

- Holistic Perspective: Modern leaders can learn the importance of seeing military action not in isolation but as part of a larger social, economic, and environmental context. Decisions on the battlefield have far-reaching implications for the community.

- Leadership by Example: Tribal leaders led from the front, sharing the same risks and hardships as their warriors. This fostered deep loyalty and respect, a quality often sought but sometimes lacking in modern hierarchical systems.

- Meritocracy and Trust: Legitimacy earned through proven competence, wisdom, and dedication to the community remains a powerful foundation for any leadership role, military or otherwise.

- Environmental Acumen: The deep understanding and respect for the environment exhibited by tribal leaders offer critical insights into sustainable warfare and the strategic importance of ecological knowledge.

- Adaptability and Resilience: The ability to adapt to changing circumstances, to innovate with limited resources, and to maintain morale in the face of overwhelming odds are timeless qualities of effective leadership.

- Community Accountability: Tribal leaders were directly accountable to their people, fostering a sense of shared purpose and ensuring that military actions aligned with the community’s values and long-term interests.

In conclusion, traditional military leadership roles in tribal structures were far more complex and nuanced than a simple "war chief" designation might suggest. They were a testament to human ingenuity, resilience, and the enduring power of community. These leaders were not just commanders of warriors; they were custodians of culture, protectors of their people, and living embodiments of wisdom forged in the crucible of survival. Their legacy serves as a potent reminder that true leadership, especially in the context of defense, transcends mere tactical brilliance and is ultimately rooted in a profound commitment to the well-being and future of the people one serves. Their shields were not just for battle, but for guarding the very soul of their societies.