Echoes of the Land: The Enduring Wisdom of Turtle Island’s Traditional Governance Systems

Turtle Island, the Indigenous name for the continent often called North America, has for millennia been home to complex and sophisticated governance systems that predated and, in many ways, surpassed the European models introduced by colonizers. Far from being primitive, these traditional systems were deeply rooted in a profound understanding of reciprocity, ecological balance, and collective well-being, offering enduring lessons for contemporary society. This article delves into the core principles, structures, and enduring legacy of these Indigenous governance models, highlighting their resilience in the face of colonial disruption and their profound relevance in today’s world.

At the heart of Indigenous governance across Turtle Island lies a philosophy distinct from Western political thought: a relational worldview. This perspective understands all beings – human, animal, plant, and spirit – as interconnected components of a vast, living system. Governance, therefore, was not merely about managing human affairs but about maintaining harmony within this broader web of relations. Decisions were not made for short-term gain or individual profit, but with a profound sense of responsibility to the land, the ancestors, and the generations yet to come – often articulated as the "Seventh Generation Principle." This principle dictates that all decisions must consider their impact seven generations into the future, fostering a long-term, sustainable approach to resource management, social policy, and inter-community relations.

One of the most widely recognized and influential examples of this sophisticated governance is the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Confederacy, whose Great Law of Peace, or Gayanashagowa, is one of the oldest living participatory democracies in the world, potentially dating back to the 12th century. The Confederacy, originally comprising the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, and Seneca Nations (later joined by the Tuscarora), united these sovereign nations under a common framework that emphasized peace, equity, and the power of reasoned discourse.

The Gayanashagowa is a meticulously structured constitution, passed down through oral tradition and encoded in wampum belts. It established a Grand Council of 50 Hoyaneh (Chiefs), chosen by Clan Mothers, who hold significant political and spiritual authority. Clan Mothers are the matriarchs of the clans, responsible for selecting, guiding, and, if necessary, deposing the Hoyaneh. This matriarchal influence ensured that women’s voices were central to governance, reflecting a balance of power and a recognition of their life-giving and community-sustaining roles. The Council operated on principles of consensus, with debates structured to ensure all perspectives were heard and a unified decision reached, embodying the Haudenosaunee phrase, "Our minds are now one." The Tree of Peace, a central symbol of the Confederacy, represents a deep understanding of peace achieved through unity and strength, with weapons buried beneath its roots. This system of checks and balances, and its emphasis on consensus and the separation of powers, is often cited as a profound influence on the framers of the United States Constitution, demonstrating the sophistication of Indigenous political thought.

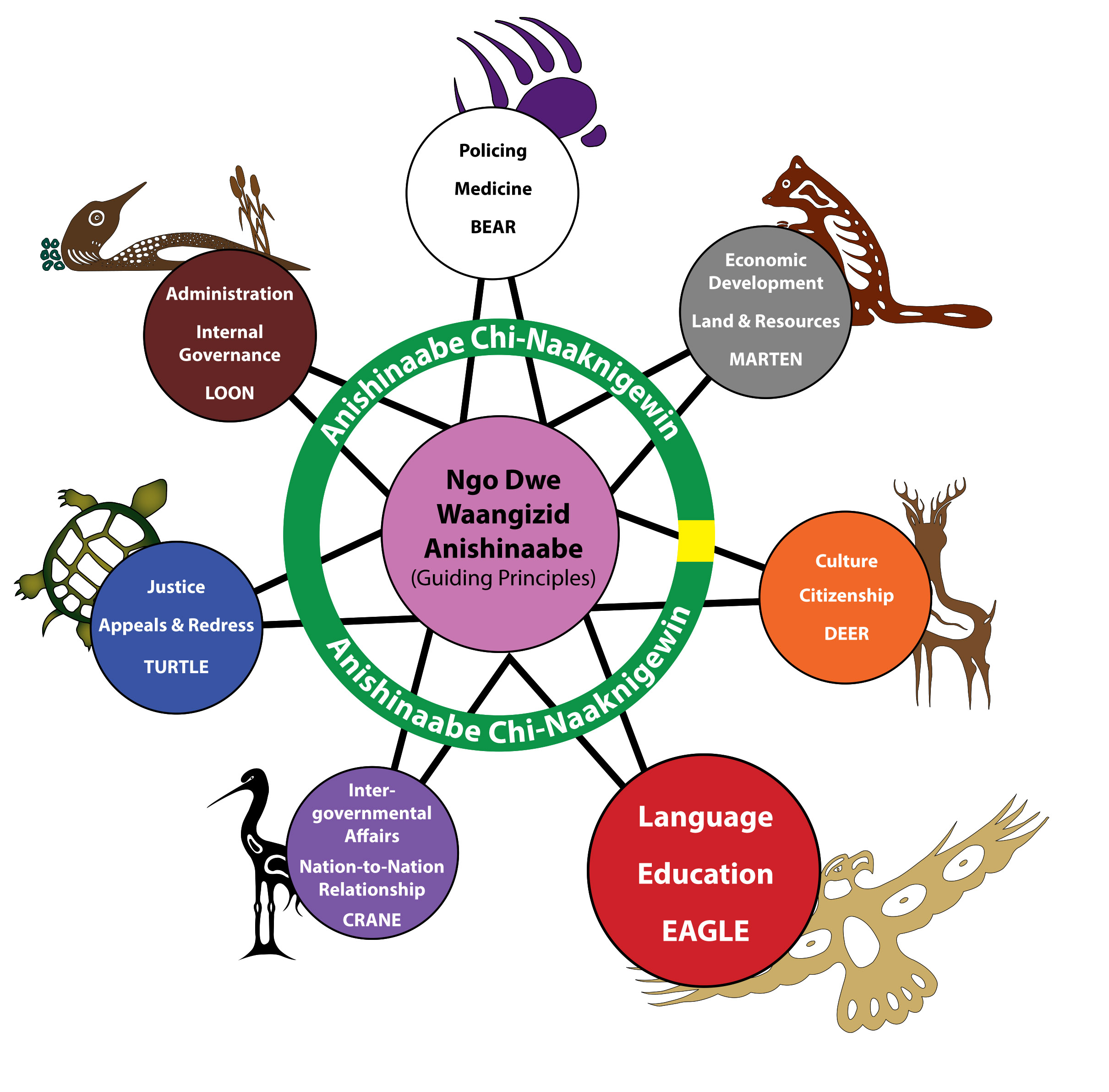

Further west, the Anishinaabe (Ojibwe, Odawa, Potawatomi, Algonquin, Saulteaux, Nipissing, Oji-Cree) nations developed governance structures guided by the Seven Grandfather Teachings: Wisdom, Love, Respect, Bravery, Honesty, Humility, and Truth. These teachings are not merely moral precepts but foundational principles for leadership and community interaction. Governance was often organized through clan systems, where individuals inherited responsibilities and roles based on their clan affiliation (e.g., Bear Clan for policing, Loon Clan for leadership). Decisions were made through community councils, where elders played a crucial advisory role, drawing upon their vast knowledge of traditions, history, and the natural world. The Midewiwin, a spiritual society, also played a significant role in maintaining cultural knowledge, healing, and ethical conduct, thus intertwining spiritual well-being with good governance.

The Lakota, Dakota, and Nakota nations, forming the Oceti Sakowin (Seven Council Fires), also demonstrated a sophisticated system of decentralized yet interconnected governance. Each "fire" was an independent nation, yet they shared a common language, culture, and a council system that allowed for collective decision-making on matters affecting the entire confederacy, such as defense or resource management. Leadership was often fluid, based on merit, wisdom, and demonstrated ability to serve the people, rather than rigid hierarchy. The Black Hills (Paha Sapa) were, and remain, central to their spiritual and political identity, embodying the sacred connection between land and governance. The pipe ceremony, a sacred ritual, was often used to solemnize agreements and decision-making processes, emphasizing the spiritual gravity of commitments.

Beyond these prominent examples, diverse governance models flourished across Turtle Island. The Coast Salish peoples of the Pacific Northwest, for instance, utilized longhouses as centers for political and social life, with hereditary chiefs and community leaders guiding affairs through extensive consultation and consensus-building, often demonstrated through the potlatch ceremony – a complex system of wealth redistribution and affirmation of social status and authority. In the Arctic, Inuit communities governed themselves through highly adaptable systems based on consensus, expertise in survival, and strong familial ties, with elders providing guidance rooted in generations of Arctic knowledge.

A striking contrast between traditional Indigenous governance and Western models lies in the concept of power. In many Indigenous systems, power was not about domination or control over others, but about responsibility and service. Leaders were expected to be humble, generous, and to act in the best interests of the entire community, often "leading from behind" or by example. The accumulation of wealth or personal prestige was secondary to the well-being of the collective. This contrasts sharply with Western hierarchical structures, where power is often concentrated, and decision-making can be top-down, frequently prioritizing individual rights or economic growth over communal or ecological health.

The arrival of European colonizers brought devastating disruption to these intricate systems. Colonial policies, such as the Indian Act in Canada and various acts in the United States, were explicitly designed to dismantle Indigenous governance, replace it with imposed municipal-style band councils, suppress languages and spiritual practices, and assimilate Indigenous peoples. The residential school system, a particularly dark chapter, aimed to "kill the Indian in the child," severing generations from their cultural, linguistic, and governance heritage. Treaties, often viewed by Indigenous nations as nation-to-nation agreements for shared land use and peace, were systematically misinterpreted and violated by colonial powers, who saw them as instruments for land surrender.

Despite these concerted efforts at subjugation, traditional governance systems have demonstrated remarkable resilience. Many communities maintained their oral traditions, ceremonies, and clan systems in secret, passing down knowledge through generations. Today, there is a powerful resurgence of Indigenous self-determination and a revitalization of traditional governance. Nations are increasingly asserting their inherent rights to govern themselves, often drawing directly from their ancestral laws and practices.

This revitalization takes many forms:

- Reclaiming Jurisdiction: Many First Nations, Métis, and Inuit communities are developing their own constitutions, laws, and justice systems, often blending traditional principles with modern administrative needs. For instance, the Nisga’a Nation in British Columbia, Canada, signed a landmark treaty that recognized their inherent right to self-government and control over their lands and resources, establishing a government rooted in both Nisga’a culture and modern democratic principles.

- Environmental Stewardship: Indigenous governance principles, with their emphasis on interconnectedness and long-term sustainability, are proving invaluable in addressing contemporary environmental crises. Indigenous-led conservation initiatives and co-management agreements for protected areas often outperform government-only approaches, demonstrating the efficacy of traditional ecological knowledge and governance.

- Restorative Justice: Traditional Indigenous justice systems, which focus on healing, reconciliation, and restoring balance within the community rather than punitive measures, are being revitalized and integrated into modern legal frameworks, offering more effective and culturally appropriate solutions to conflict.

- Cultural Revitalization: The resurgence of language, ceremony, and traditional arts is intrinsically linked to governance, as these elements carry the laws, histories, and values that underpin traditional leadership and community cohesion.

The enduring wisdom of Turtle Island’s traditional governance systems offers profound lessons for the entire world. Their emphasis on collective well-being, ecological stewardship, long-term thinking, consensus-building, and relational accountability provides powerful alternatives to the often-fragmented and short-sighted governance models prevalent globally. As humanity grapples with complex challenges like climate change, social inequality, and political polarization, looking to the profound, time-tested wisdom of Indigenous governance is not just an act of respect; it is a vital step toward imagining more sustainable, equitable, and harmonious futures for all. The echoes of the land speak of a path forward, rooted in ancient knowledge yet profoundly relevant to the modern age.