Ancient Wisdom, Modern Solutions: The Power of Traditional Ecological Knowledge in a Changing World

The Earth is in crisis. Climate change accelerates, biodiversity plummets, and resource scarcity looms large. In the face of these unprecedented challenges, humanity scrambles for solutions, often turning to cutting-edge technology and complex scientific models. Yet, a profound and enduring wellspring of wisdom, honed over millennia and deeply rooted in place, offers an equally vital, if often overlooked, path forward: Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK).

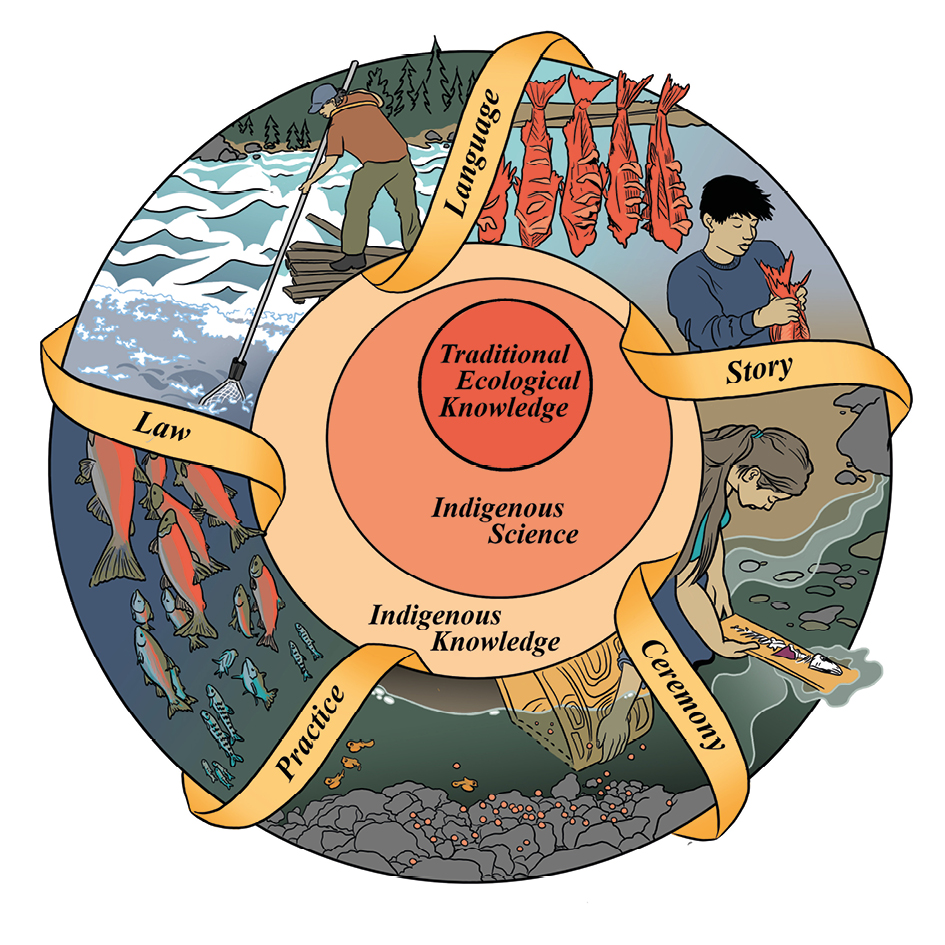

TEK, also known as Indigenous Knowledge or Local Ecological Knowledge, encompasses the cumulative body of knowledge, practices, and beliefs about the relationship of living beings (including humans) with their environment, which is handed down through generations by cultural transmission. It is holistic, practical, spiritual, and intrinsically linked to the land, sea, and sky. Unlike the reductionist approach often seen in Western science, TEK views ecosystems as interconnected webs where every element plays a role, and human actions have ripple effects. As Robin Wall Kimmerer, a botanist and member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, eloquently states in her book "Braiding Sweetgrass," "Science asks how, and traditional knowledge asks how and also why."

The applications of TEK are vast and increasingly recognized as indispensable for addressing the multifaceted environmental and social challenges of our time. From sustainable resource management to climate change adaptation, biodiversity conservation, and even public health, integrating this ancient wisdom with contemporary scientific understanding holds the key to a more resilient and equitable future.

Reimagining Sustainable Resource Management

One of the most immediate and impactful applications of TEK lies in sustainable resource management. Indigenous communities have long managed their territories with an eye towards intergenerational well-being, understanding that the health of the land directly impacts their own.

Forestry and Fire Management: In many parts of the world, a century of fire suppression policies, driven by Western scientific approaches, has led to an accumulation of fuel, resulting in increasingly devastating megafires. Indigenous fire management, or "cultural burning," offers a powerful counter-narrative. Practices like those of the Karuk Tribe in California or Aboriginal communities in Australia involve controlled, low-intensity burns that mimic natural fire regimes. These burns reduce fuel loads, promote the growth of fire-resistant species, create mosaic landscapes that break up large fires, and enhance biodiversity. A study published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences found that areas managed with Indigenous burning practices experienced significantly less severe wildfires. As Margo Robbins, a Yurok tribal member and co-founder of the Cultural Fire Management Council, articulates, "We don’t just burn to reduce fuels. We burn to tend the land, to promote the plants we use, to help the animals. It’s about a relationship, not just a problem."

Fisheries and Water Management: Traditional fishing practices often incorporate seasonal restrictions, gear limitations, and knowledge of fish migration patterns to ensure sustainable harvests. For instance, the Pacific Islanders’ "tabu" system, which designates certain areas or species as off-limits for specific periods, has parallels with modern marine protected areas but is often more dynamic and culturally embedded. Similarly, ancient irrigation systems in regions like the Andes or North Africa demonstrate sophisticated water harvesting and distribution techniques that minimize waste and adapt to local hydrology, often outperforming modern, large-scale infrastructure in terms of efficiency and ecological impact.

Biodiversity Conservation and Ecosystem Restoration

Indigenous territories, despite occupying only about 25% of the world’s land area, are home to an estimated 80% of the planet’s biodiversity. This is no coincidence. TEK-based practices are inherently geared towards fostering and maintaining a rich variety of life.

Sacred Natural Sites: Across cultures, specific forests, mountains, rivers, or groves are designated as sacred. These sites, often protected by spiritual beliefs and community norms, act as de facto conservation areas, safeguarding critical habitats and rare species. The sacred groves of India, for example, are remnants of ancient forest ecosystems, preserving unique flora and fauna that have disappeared from surrounding deforested areas. This recognition of the intrinsic value of nature, beyond its utilitarian worth, is a cornerstone of TEK-driven conservation.

Ethnobotany and Traditional Agriculture: The knowledge of medicinal plants, edible species, and their ecological relationships is immense within Indigenous communities. This ethnobotanical wisdom is crucial for discovering new medicines, understanding plant-animal interactions, and restoring degraded ecosystems. Traditional agricultural systems, such as the milpa system in Mesoamerica, which intercrops maize, beans, and squash, exemplify polyculture that enhances soil fertility, reduces pest outbreaks, and provides diverse nutritional benefits, far exceeding the ecological resilience of industrial monocultures. The genetic diversity preserved in traditional seed banks is a vital resource for developing climate-resilient crops.

Climate Change Adaptation and Resilience

Indigenous communities, often living on the front lines of climate change, possess invaluable knowledge for adaptation and building resilience. Their long-term observation of environmental patterns allows for early warning systems and adaptive strategies.

Observational Knowledge and Early Warning: In the Arctic, Inuit elders can predict weather patterns and ice conditions with remarkable accuracy based on subtle changes in wind, cloud formations, and animal behavior – knowledge critical for safe travel and hunting in a rapidly changing environment. Their observations of glacial retreat, permafrost thaw, and shifts in wildlife populations provide crucial data that complements scientific monitoring. "Our elders have seen these changes before," says an Inuit leader, "not exactly like this, but their wisdom helps us understand what is happening and how to prepare."

Resilient Infrastructure and Practices: In coastal communities, traditional knowledge informs the strategic placement of settlements, the construction of storm-resistant housing using local materials, and the restoration of natural buffers like mangrove forests or coral reefs to mitigate the impacts of sea-level rise and storm surges. The traditional knowledge of water harvesting and drought-resistant crop varieties is becoming increasingly vital in regions experiencing prolonged dry spells.

Public Health and Food Security

TEK also plays a significant role in public health and food security, offering culturally appropriate and sustainable solutions.

Traditional Medicine: An estimated 80% of the world’s population still relies on traditional medicine for primary healthcare, much of it derived from plant-based remedies passed down through generations. The knowledge held by traditional healers and shamans represents a vast pharmacopeia, with countless compounds yet to be investigated by modern science. However, the ethical implications of bioprospecting – ensuring fair and equitable benefit sharing – are paramount.

Food Sovereignty and Nutrition: The revitalization of traditional food systems can combat malnutrition and food insecurity. Many Indigenous diets, rich in locally sourced, diverse, and nutrient-dense foods, offer healthier alternatives to processed modern diets. Promoting the cultivation and consumption of traditional crops not only enhances nutrition but also strengthens cultural identity and economic self-sufficiency for communities.

Challenges and Ethical Considerations

While the benefits of applying TEK are clear, its integration with Western science and policy is not without challenges. These include issues of intellectual property rights, potential for cultural appropriation, power imbalances, and the need for genuine, respectful collaboration.

Protecting Intellectual Property: The knowledge held by Indigenous communities is often collective and sacred, not a commodity to be exploited. Mechanisms for Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC) are essential to ensure that communities control how their knowledge is used and that they receive fair benefits from any commercial applications.

Bridging Epistemologies: Western science and TEK often operate on different epistemological frameworks. Science seeks universal laws through reductionist analysis, while TEK is place-based, holistic, and often incorporates spiritual dimensions. True integration requires mutual respect and a willingness to learn from different ways of knowing, rather than simply "extracting" useful bits of TEK. This means co-creating research questions, methodologies, and outcomes.

Capacity Building and Support: Many Indigenous communities face systemic barriers, including lack of resources and historical marginalization. Supporting Indigenous-led initiatives, strengthening traditional governance structures, and investing in intergenerational knowledge transfer programs are crucial for revitalizing and applying TEK effectively.

The Path Forward: Weaving Two-Eyed Seeing

The future of environmental stewardship and human well-being lies in "Two-Eyed Seeing," a concept from Mi’kmaw Elder Albert Marshall, which advocates for learning to see from one eye with the strengths of Indigenous ways of knowing and from the other eye with the strengths of Western ways of knowing, and to use both eyes together.

Integrating TEK is not about abandoning modern science but enriching it. It is about recognizing that Indigenous peoples are not merely stakeholders but vital knowledge holders and partners in charting a sustainable course for humanity. By listening deeply, respecting diverse worldviews, and fostering genuine collaboration, we can unlock the full potential of traditional ecological knowledge to heal our planet and build a future where both human and non-human communities thrive in harmony. The echoes of ancient wisdom, once whispers in the wind, are now becoming a guiding chorus for a world desperately seeking balance.