Guardians of Hózhó: The Navajo Nation’s Enduring Fight for Environmental Justice

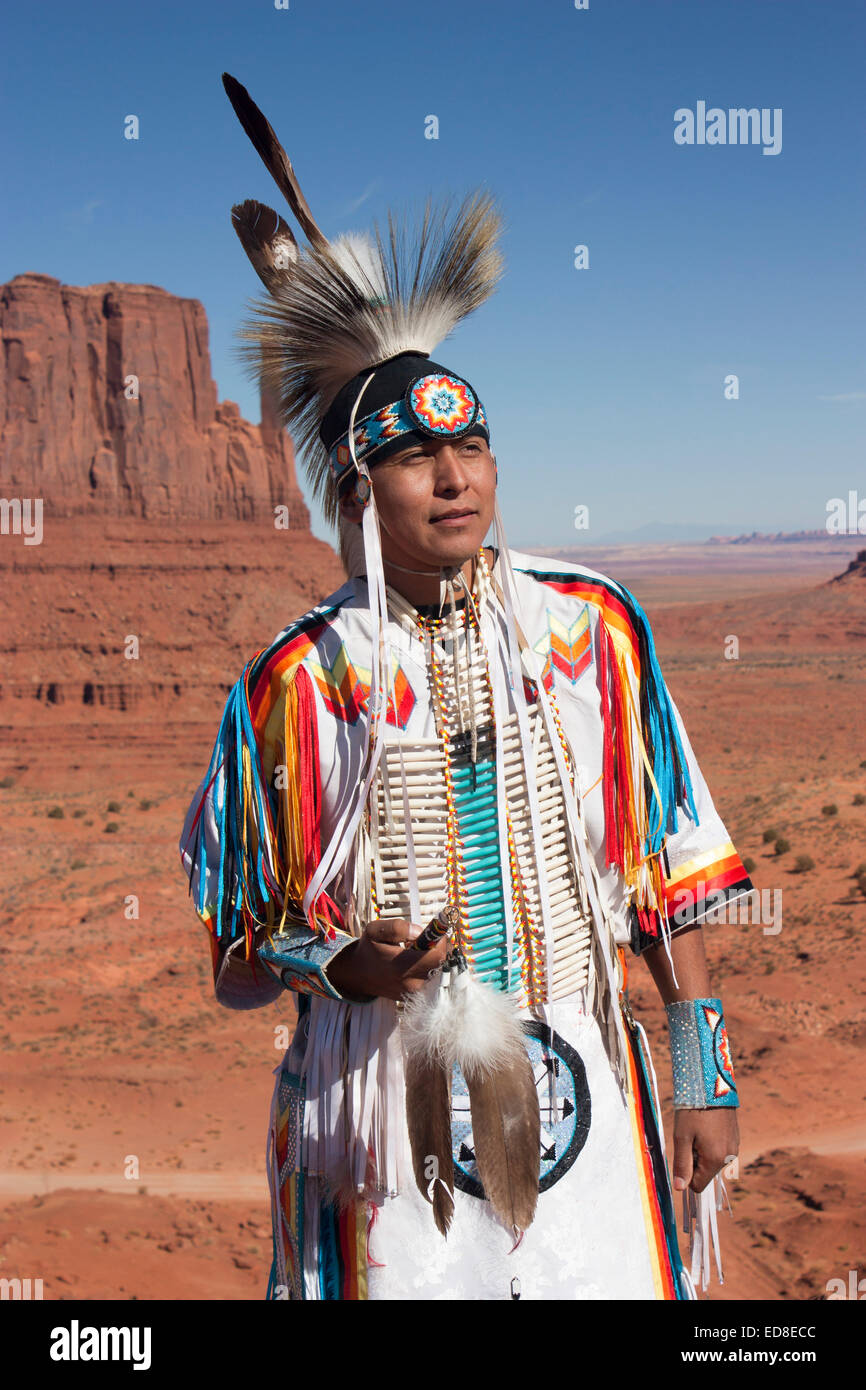

The Navajo Nation, Diné Bikéyah, spans over 27,000 square miles across Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah – a territory larger than 10 U.S. states. It is a land of breathtaking beauty: vast mesas, deep canyons, and a sky that stretches into eternity. Yet, beneath this pristine facade lies a landscape profoundly scarred, a testament to decades of resource exploitation that has left a toxic legacy. For the Diné (the Navajo people), environmental protection is not merely a policy agenda; it is a profound cultural imperative, a relentless struggle for justice, and a daily commitment to restoring Hózhó – balance and harmony – to their sacred land.

The Navajo Nation’s environmental battle is unique in its scale, its historical depth, and its philosophical underpinnings. Unlike most environmental movements, which often react to new threats, the Diné have been contending with existing, deeply embedded contamination for generations. Their fight is against an inheritance of poisoned water, irradiated soil, and compromised air, a direct result of their land being deemed a sacrifice zone for the energy demands of the wider American economy.

The Uranium Scars: A Cold War Legacy

The most devastating chapter in this environmental saga began during the Cold War. From the 1940s to the 1980s, the Navajo Nation became the primary source of uranium for the U.S. nuclear weapons program. Over 500 abandoned uranium mines litter the reservation, alongside numerous unregulated waste piles. Navajo men, often working without adequate protection, mined the radioactive ore, bringing dust into their homes, contaminating water sources, and unwittingly exposing their families to silent killers.

"My grandfather died of lung cancer, my uncle died of kidney disease, and my aunt had a rare form of blood cancer," recounts Mae Nakai, a community advocate from Monument Valley, her voice heavy with the collective grief of a generation. "They all worked in the mines. We didn’t know the dangers then. The government just wanted the uranium."

The environmental and health consequences have been catastrophic and enduring. Elevated rates of cancer, kidney disease, and respiratory illnesses plague communities living near the abandoned mines. Radiation contamination persists in water wells, soil, and even the dust that blows across homes. The infamous Church Rock uranium mill spill in 1979, which released 94 million gallons of radioactive waste and acidic tailings into the Rio Puerco, remains the largest single release of radioactive material in U.S. history, surpassing even Three Mile Island in volume. Yet, it received a fraction of the public attention and remediation efforts.

For decades, the federal government was slow to acknowledge its responsibility. It wasn’t until the early 2000s, driven by persistent advocacy from the Navajo Nation and environmental groups, that federal agencies like the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), Department of Energy (DOE), and Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) began to coordinate efforts to assess and remediate the sites. But the task is monumental, costly, and moves at a glacial pace. Many communities still live with the immediate threat of contamination, their access to clean water compromised daily.

Beyond Uranium: Coal, Water, and Air

While uranium remains a critical focus, the Navajo Nation has also grappled with the impacts of coal mining and coal-fired power generation. For decades, the Navajo Generating Station (NGS) in Page, Arizona, was one of the largest coal-fired power plants in the West, providing electricity to millions and water to Phoenix and Los Angeles via the Central Arizona Project. It was also a significant source of air pollution, contributing to regional haze and respiratory issues. The adjacent Kayenta Coal Mine, operated by Peabody Energy, supplied NGS and carved deep scars into the Black Mesa landscape, depleting precious groundwater resources through its use of a slurry pipeline.

The closure of NGS in 2019 was a bittersweet victory. Environmentally, it marked a significant step towards cleaner air and reduced carbon emissions. Economically, however, it delivered a heavy blow, eliminating hundreds of well-paying jobs and millions in tribal revenue, highlighting the complex balancing act between economic development and environmental health.

Water scarcity is another existential threat. Situated in the arid Southwest, the Navajo Nation faces the escalating impacts of climate change, including prolonged droughts and diminished flows in the Colorado River, its primary water source. Many remote communities still lack access to running water, relying on hauling water from communal wells, some of which are themselves contaminated. The fight for clean and adequate water is intertwined with the legacy of resource extraction and the ongoing challenges of infrastructure development.

The Navajo Nation Environmental Protection Agency (NNEPA): A Model of Sovereignty

In response to these pervasive challenges, the Navajo Nation established its own Environmental Protection Agency (NNEPA) in 1993. This was a pivotal move, asserting tribal sovereignty over environmental governance. NNEPA operates with the authority of a state EPA, developing and enforcing its own environmental laws and regulations, often more stringent than federal standards, particularly in areas like cultural resource protection.

"Our approach is different," explains Dr. Karletta Chief, an environmental scientist and member of the Navajo Nation. "We don’t just look at the scientific data; we integrate our traditional knowledge, our Diné values. For us, the land, water, and air are relatives, not just resources. Our policies reflect that."

NNEPA’s work is broad and challenging. Its Superfund Program manages the assessment and cleanup of abandoned uranium mines and other hazardous waste sites. The Water Quality Program monitors water bodies, regulates discharges, and works to expand access to safe drinking water. The Air Quality Program monitors industrial emissions and addresses regional air pollution. The Waste Management Program tackles solid waste issues, including illegal dumping which plagues vast, remote areas.

A critical aspect of NNEPA’s mission is environmental justice. They prioritize communities disproportionately affected by pollution, ensuring that their voices are heard and their concerns addressed. This often means navigating complex legal frameworks and engaging in persistent advocacy with federal agencies to secure funding and resources for cleanup efforts that have been historically underfunded.

Grassroots Activism and Cultural Resilience

Beyond the formal structures of NNEPA, grassroots organizations and community activists play a vital role. Groups like the Navajo Uranium Radiation Victims Committee (NURVC) and Black Mesa Trust have tirelessly advocated for their communities, sharing personal stories, raising awareness, and demanding accountability. These organizations embody the deep resilience and determination of the Diné people.

Their activism is rooted in Diné Hózhó, a holistic philosophy that emphasizes balance, beauty, and harmony in all aspects of life – physical, mental, spiritual, and environmental. The land, Nahasdzáán Shimá (Mother Earth), and the sky, Yádiłhił Shizhé’é (Father Sky), are revered as living entities, fundamental to identity and well-being. To harm the environment is to harm oneself, one’s community, and future generations.

"Our ancestors taught us that we are stewards of this land," says Peterson Zah, former Navajo Nation President. "We have a sacred responsibility to protect it for those who are not yet born. This is not just about laws; it’s about who we are as a people."

This cultural framework provides a powerful moral compass and an unwavering resolve in the face of daunting environmental challenges. It drives efforts to transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy, particularly solar, which holds immense potential on the sun-drenched reservation. Several large-scale solar projects are now operational or under development, representing a pathway to energy independence, job creation, and a cleaner future.

The Path Forward: Healing and Hope

The Navajo Nation’s environmental protection efforts represent a living testament to resilience, self-determination, and a profound cultural connection to land. The journey is far from over. Hundreds of uranium sites still await remediation, water infrastructure remains inadequate for many, and the impacts of climate change intensify.

However, the Diné continue to lead with wisdom and determination. They are not merely recipients of environmental policy but active architects of their own sustainable future. Their integrated approach, blending modern science with ancient wisdom, offers a powerful model for indigenous communities worldwide and a critical lesson for a planet grappling with ecological crisis.

The struggle for environmental justice on the Navajo Nation is a microcosm of global challenges, but it is met with an unwavering commitment to Hózhó. It is a fight to heal the land, protect the people, and ensure that the sacred balance is restored, not just for the Diné, but for the health of all. Their ongoing efforts are a powerful reminder that true environmental stewardship begins with reverence for the Earth, and that justice for the land is inseparable from justice for its people.