Echoes in Stone: The Enduring Legacy of Pre-Contact American Tool Technology

In the vast, untamed landscapes of the pre-contact Americas, long before the arrival of European ships, human ingenuity sculpted survival from the very earth. From the icy plains of the Arctic to the dense Amazonian rainforests, and from the towering peaks of the Andes to the sprawling North American plains, Indigenous peoples developed a sophisticated and diverse array of stone tools. These artifacts, often dismissed by the untrained eye as mere rocks, are in fact the indelible fingerprints of cultures, economies, and adaptations, revealing a technological prowess that underpinned millennia of human flourishing. Far from rudimentary, pre-contact American stone tool technology represents a dynamic continuum of innovation, deeply intertwined with the environment, social structures, and spiritual beliefs of its makers.

The narrative of American lithic technology often begins with the iconic Clovis point. Emerging around 13,500 years ago, these distinctive, fluted projectile points are synonymous with some of the earliest widely accepted human presence south of the North American ice sheets. Characterized by a channel, or "flute," removed from the base on both faces, likely to facilitate hafting onto a spear shaft, Clovis points were remarkably effective for hunting megafauna like mammoths and mastodons. Their widespread distribution across North America, from the Pacific to the Atlantic, suggests a highly mobile population sharing a common, successful hunting technology. The precision required to craft a Clovis point speaks volumes about the knappers’ skill, understanding of lithic mechanics, and perhaps, a shared cultural identity expressed through material culture.

However, the Clovis story is not the whole story. Archaeological discoveries over the past few decades have challenged the long-held "Clovis First" paradigm, pushing back the timeline of human arrival and suggesting earlier, distinct technological traditions. Sites like Monte Verde in Chile, dating back over 14,500 years, and Paisley Caves in Oregon, with evidence of human occupation at least 14,000 years ago, have yielded different types of stone tools, alongside organic materials. These pre-Clovis toolkits often include simpler flake tools, choppers, and bifacial implements, reflecting diverse adaptations to varied environments and resource availability, suggesting multiple waves of migration or different technological trajectories prior to the widespread adoption of Clovis technology. This ongoing debate underscores the complexity of reconstructing early American history and highlights the ingenuity of diverse groups adapting to novel environments.

As human populations expanded and diversified across the continents, so too did their stone tool technologies. Regional specialization became a hallmark, with tools exquisitely tailored to specific ecological niches and subsistence strategies. In the Arctic and Subarctic, for instance, microblade technology flourished. These tiny, razor-sharp blades, often set into bone or antler handles, were ideal for processing caribou, marine mammals, and fish, and for crafting tools from bone, ivory, and wood in a harsh, resource-scarce environment. Further south, in the temperate forests of the Northeast and Great Lakes regions, ground stone tools like axes, adzes, and gouges became prevalent. These tools, painstakingly shaped and polished, were essential for woodworking, clearing forests for agriculture, building canoes, and constructing dwellings, reflecting a shift towards more settled lifestyles and forest resource management.

On the vast North American Plains, the successors to Clovis, such as the Folsom and Plano traditions, continued to refine projectile point technology for hunting bison. Folsom points, even more delicately fluted than Clovis, were likely designed for smaller, faster bison species. Later Plano points, characterized by their lanceolate shape and often exquisite parallel flaking, represent the pinnacle of aerodynamic design for spear throwers (atlatls), crucial for bringing down large herds. Along with projectile points, the Plains toolkit included a range of scrapers for hide processing, knives for butchering, and specialized tools for bone and antler work, reflecting a sophisticated understanding of their primary prey and its multiple uses.

In the arid Southwest, where agriculture eventually took root, toolkits adapted to processing plant foods. Manos and metates, grinding stones used for milling wild seeds and later maize, became indispensable. Digging sticks tipped with stone points, hoes, and choppers were developed for cultivation and harvesting. Further south, in Mesoamerica and the Andean regions, agricultural tools became even more specialized, supporting the rise of complex civilizations. Obsidian, a volcanic glass, was particularly prized in these regions due to its exceptional sharpness, allowing for the creation of blades sharper than modern surgical steel. Extensive trade networks developed to distribute obsidian, with sources like Pachuca in central Mexico providing material for tools across vast areas, highlighting the economic and social significance of lithic resources.

The materials chosen for stone tool production were as diverse as the tools themselves. Chert (flint), obsidian, quartzite, basalt, and even slate were selected based on their knappability (how well they fracture) and availability. The ability to identify, locate, and extract high-quality lithic raw material was a critical skill. Often, desired materials were not locally available, leading to the development of sophisticated trade networks that spanned hundreds, even thousands, of miles. Archaeological sourcing studies, which identify the geological origin of a stone artifact, provide invaluable insights into ancient social interactions, territorial boundaries, and economic exchange. For example, specific types of chert from Ohio or obsidian from Glass Buttes in Oregon have been found hundreds of miles from their geological source, indicating extensive pre-contact trade routes.

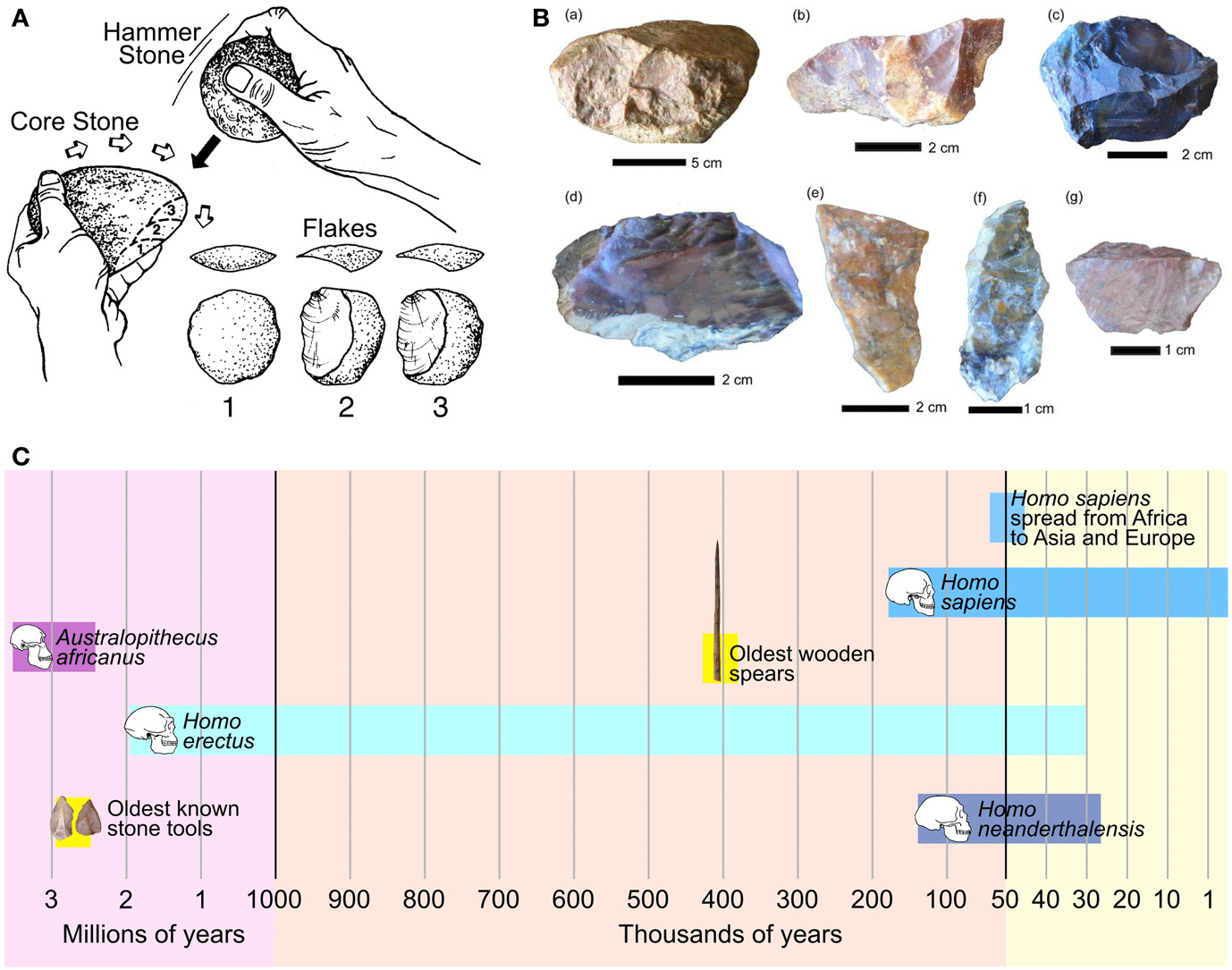

The manufacturing process itself, known as flintknapping, was a highly skilled craft. It involved a series of precise steps:

- Percussion Flaking: Using a "hammerstone" (hard hammer percussion) or an antler billet (soft hammer percussion) to strike a core of stone, detaching flakes. This stage shaped the general form of the tool.

- Pressure Flaking: Employing a pointed tool, often made of antler or bone, to apply localized pressure along the edge of the preform, detaching small, controlled flakes. This refined the edge, thinned the tool, and created the final sharp, serrated, or denticulate edge.

- Grinding and Polishing: For ground stone tools, this involved patiently abrading the stone against a coarser surface with water and sand, then polishing it to a smooth finish, enhancing durability and effectiveness for tasks like chopping wood.

- Heat Treatment: Many lithic materials, particularly chert, were intentionally heated to high temperatures in controlled environments. This process altered the stone’s crystalline structure, making it more brittle and thus easier to flake precisely, demonstrating a sophisticated understanding of material science.

Beyond the ubiquitous projectile point, the range of stone tools was astonishing. Scrapers, with various edge angles, were used for processing animal hides, woodworking, and food preparation. Choppers served for heavy-duty tasks like breaking bones or roughing out wood. Drills and awls, with their pointed tips, pierced hides for clothing, created holes in wood or shell, and facilitated intricate craftwork. Knives, adzes (for shaping wood), axes (for felling trees), and a multitude of specialized food processing tools like mortars, pestles, manos, and metates, all contributed to the daily sustenance and cultural development of these societies. Each tool was a testament to purpose-driven design, reflecting a deep understanding of physics, material properties, and the task at hand.

The significance of stone tool technology extended far beyond mere utility. It was a cornerstone of social organization, cultural identity, and knowledge transmission. The acquisition of knapping skills was a long and arduous apprenticeship, passed down through generations, indicating specialized roles within communities. The quality and craftsmanship of certain tools could denote status, wealth, or ritual importance. Elaborate, non-utilitarian blades found in caches or burials suggest ceremonial functions, serving as markers of power, belief, or artistic expression. Furthermore, the development and adaptation of toolkits reflect human intelligence in the face of environmental change, resource fluctuations, and evolving subsistence needs, driving innovation and shaping the trajectory of countless cultures.

The stone tools left behind by the Indigenous peoples of the pre-contact Americas are more than just archaeological curiosities. They are a profound archive of human endeavor, a silent testament to extraordinary ingenuity, resilience, and adaptability. From the razor-sharp obsidian blades of Mesoamerica to the finely fluted Clovis points of the North American plains, these artifacts speak volumes about the intricate relationship between humans and their environment. They remind us that for millennia, the Americas were home to vibrant, technologically advanced societies who masterfully shaped the world around them, leaving behind a legacy etched forever in stone. Their understanding of materials, their manufacturing prowess, and their innovative spirit continue to inspire awe and provide invaluable insights into the rich tapestry of human history.