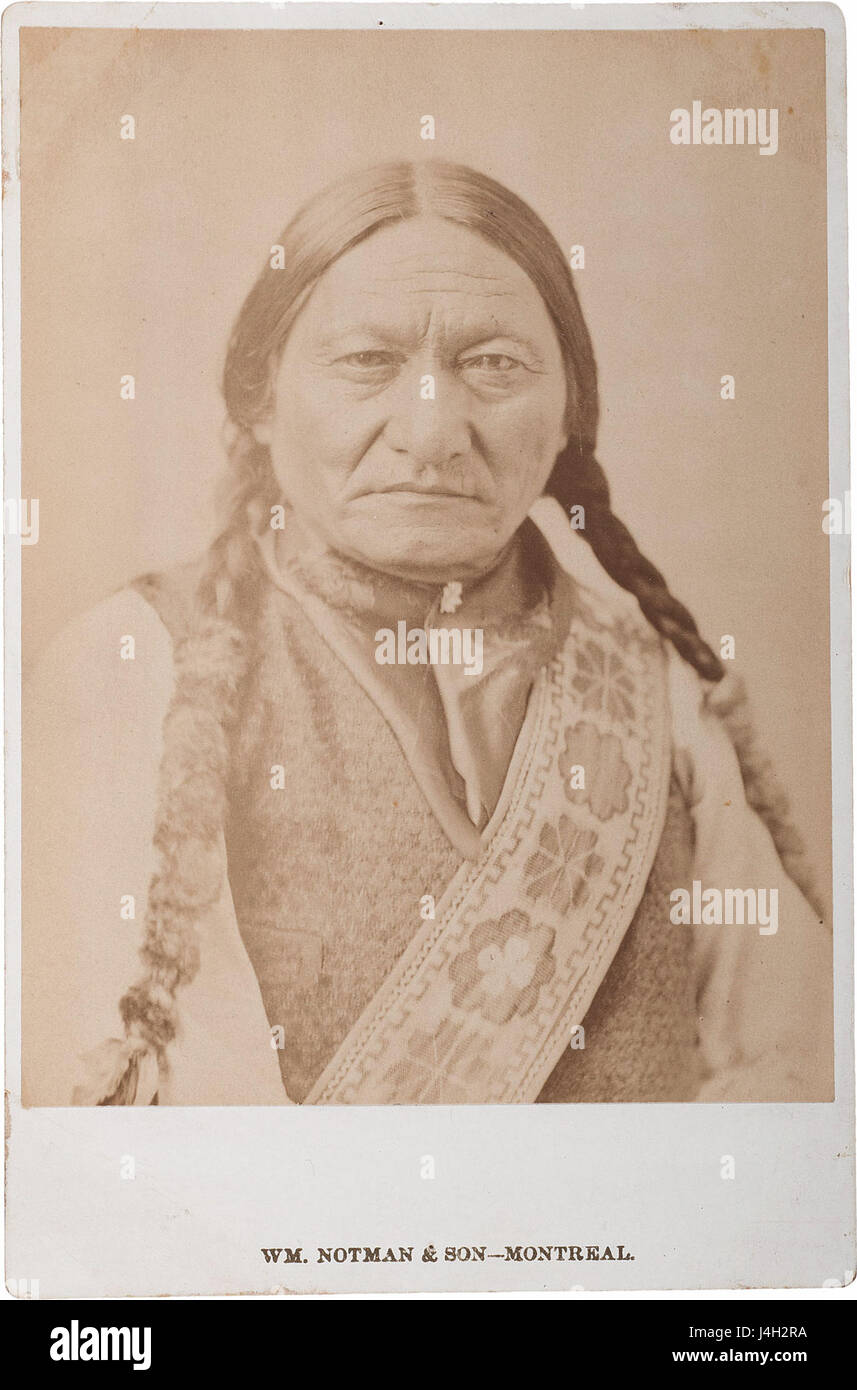

The Unbowed Spirit: Sitting Bull’s Enduring Legacy of Resistance

In the annals of American history, few figures loom as large or as defiantly as Tatanka Iyotake – Sitting Bull. A Hunkpapa Lakota holy man, chief, and warrior, his name is synonymous with the fierce and unyielding resistance mounted by the Indigenous peoples of the Great Plains against the relentless tide of American expansion. His life, marked by spiritual vision, strategic brilliance, and an unwavering commitment to his people’s sovereignty, culminated in an iconic victory that stunned a nation, and an enduring legacy that continues to inspire.

Born around 1831 near the Grand River in present-day South Dakota, Sitting Bull’s early life was steeped in the rich traditions of the Lakota. He distinguished himself early, counting his first coup at the age of 14, and quickly earning a reputation not just as a brave warrior, but as a deep thinker and a wicȟaša wakȟáŋ – a holy man. His spiritual insights and prophetic visions were as vital to his leadership as his military prowess. He understood that true resistance was not merely about winning battles, but about preserving a way of life, a spiritual connection to the land, and the very identity of his people.

The mid-19th century brought an escalating crisis to the Lakota and their allies. The concept of "Manifest Destiny" fueled an insatiable hunger for land, gold, and resources. Treaties were signed and swiftly broken, buffalo herds were decimated to starve the tribes into submission, and the advancing railroads carved through sacred hunting grounds. The Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868, intended to guarantee the Lakota their lands, including the sacred Black Hills, proved to be little more than a temporary reprieve, shattered by the discovery of gold in 1874.

Sitting Bull stood as a bulwark against this encroaching tide. He famously refused to sign any treaties with the U.S. government, viewing them as inherently illegitimate and a betrayal of his people’s inherent rights. "I was born on this land," he declared, "and I have a right to remain on it." His authority was not derived from a hereditary title, but from his profound spiritual power and his ability to unite disparate bands of Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapaho under a common cause. He preached self-reliance and the preservation of traditional ways, urging his people to resist assimilation and to fight for their freedom.

The climax of Sitting Bull’s resistance came during the Great Sioux War of 1876-77. As U.S. military campaigns intensified, aimed at forcing all "hostile" Lakota onto reservations, Sitting Bull organized a massive encampment of thousands of warriors and their families in the Little Bighorn Valley. It was here, during a grueling Sun Dance ceremony in early June 1876, that Sitting Bull received a powerful vision. After enduring 50 self-inflicted cuts and dancing for hours, he foresaw "soldiers falling into our camp upside down," a clear sign of an impending victory over the white invaders.

This vision electrified his people, imbuing them with renewed courage and determination. Though often seen as a spiritual leader rather than a direct battlefield commander, Sitting Bull’s role in the subsequent Battle of the Little Bighorn (June 25-26, 1876) was paramount. He was the architect of the resistance, the spiritual anchor, and the unifying force that brought together legendary warriors like Crazy Horse, Gall, and Rain-in-the-Face. His presence and the power of his vision created an unshakeable resolve within the Lakota and Cheyenne camp.

The battle itself was a stunning defeat for the U.S. Army. Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer, leading the 7th Cavalry, divided his forces and attacked the massive encampment. The combined Lakota and Cheyenne warriors, inspired by Sitting Bull’s vision and expertly led by their war chiefs, overwhelmed Custer’s detachment, annihilating him and over 200 of his men. The victory sent shockwaves across America, a brutal reminder that the Indigenous peoples of the Plains would not be easily conquered.

However, the victory was short-lived. The U.S. government responded with overwhelming force. For Sitting Bull and his followers, the choice was clear: surrender to reservation life or flee. Unwilling to abandon their freedom, Sitting Bull led his people north, seeking refuge in "Grandmother’s Country" – Canada. For four years, they endured harsh winters and dwindling buffalo herds, constantly pursued by both American and Canadian authorities. His refusal to surrender was absolute. "I wish it to be remembered that I was the last man of my tribe to surrender my rifle," he stated upon crossing into Canada, a testament to his unyielding spirit.

By 1881, starvation and the inability to sustain his people in Canada forced Sitting Bull to make the difficult decision to return to the United States and surrender. He was imprisoned for two years at Fort Randall before being moved to the Standing Rock Reservation. Even on the reservation, Sitting Bull remained a defiant symbol of resistance. He refused to adopt white customs, continued to advocate for his people’s rights, and resisted efforts to break up tribal lands. His fame even led him to a brief stint with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show in 1885, where he was a star attraction, though he used the opportunity to speak out against the injustices faced by his people.

The final chapter of Sitting Bull’s life unfolded amidst the Ghost Dance movement of 1890. This spiritual revival, which promised a return to traditional ways and the disappearance of the white man, spread rapidly among the disheartened tribes. While Sitting Bull was not a proponent of the Ghost Dance, his stature and influence made him a natural focal point for government fear and suspicion. Fearing he would incite an uprising, U.S. Indian Agent James McLaughlin ordered his arrest.

On December 15, 1890, Lakota police, under orders from the U.S. government, attempted to arrest Sitting Bull at his cabin on the Grand River. A struggle ensued, and in the chaos, Sitting Bull was shot and killed. Just two weeks later, the massacre at Wounded Knee Creek would tragically mark the end of armed Indigenous resistance on the Plains.

Sitting Bull’s legacy, however, far outlived his physical presence. He stands as an enduring symbol of courage, integrity, and an unshakeable commitment to freedom. He was a visionary who understood the spiritual roots of his people’s existence, a strategist who united disparate factions, and a leader who never compromised his principles. His unwavering defiance in the face of overwhelming odds continues to inspire not only Indigenous peoples fighting for sovereignty and cultural preservation but anyone who stands against injustice.

His words, "Let us put our minds together and see what life we can make for our children," resonate as a timeless call for unity and forward-thinking. Sitting Bull’s resistance was not merely a reaction to oppression; it was an affirmation of a profound spiritual connection to the land and a testament to the indomitable human spirit. He remains, to this day, the unbowed chief, the holy man whose vision of freedom refused to die, a true embodiment of the spirit of resistance.