The Shield and the Sword: The US Army’s Complex Role in Native American Conflicts

The story of the United States Army is often told through narratives of valor and nation-building, a force forged in the crucible of revolution, defending democracy, and projecting power. Yet, woven into this tapestry is a darker, more complex thread: its persistent and often brutal role in the subjugation of Native American peoples. For nearly a century and a half, from the nascent republic’s expansion to the closing of the frontier, the US Army served as both the shield for American settlers and the sword wielded against indigenous nations, fundamentally shaping the continent’s demographic and cultural landscape. This era, marked by broken treaties, forced removals, and bloody conflicts, remains a critical, often uncomfortable, chapter in American history, revealing the tragic human cost of westward expansion.

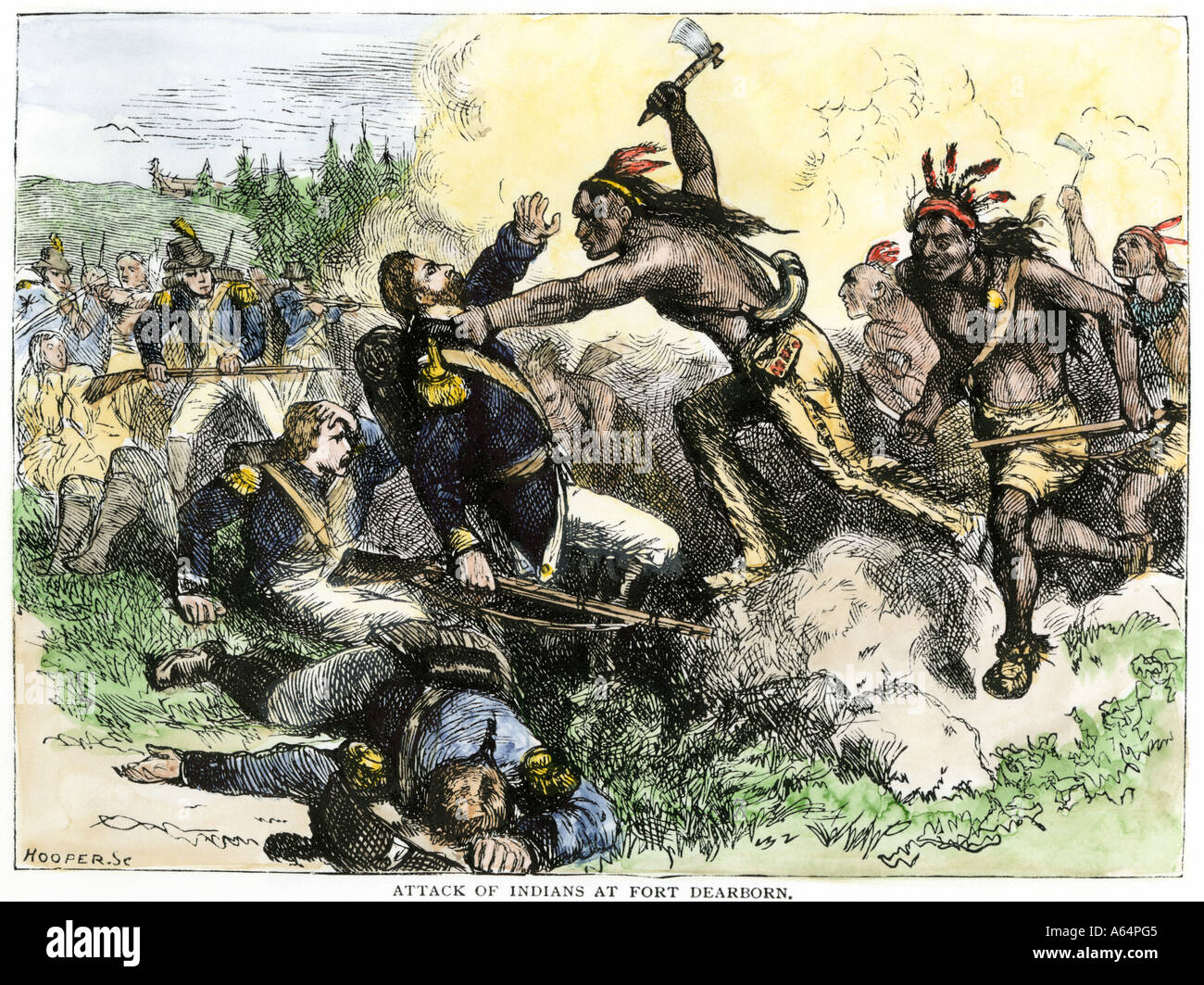

In the early days of the republic, the fledgling US Army, alongside state militias, was primarily engaged in securing the frontier, pushing back against Native American confederacies that resisted settler encroachment. Post-Revolutionary War, conflicts flared in the Ohio Valley as American settlers streamed west. Tribes like the Miami, Shawnee, and Delaware, often supplied by the British, fiercely defended their ancestral lands. General Anthony Wayne’s victory at the Battle of Fallen Timbers in 1794 was a decisive moment, leading to the Treaty of Greenville in 1795, which ceded vast tracts of land to the United States. This pattern—military victory followed by land cession—would become a grim precursor for future interactions. The army’s initial role, therefore, was to establish federal authority and protect American expansion, even if it meant displacing existing populations.

The early 19th century brought an ideological shift, epitomized by President Andrew Jackson’s policy of "Indian Removal." Despite the Supreme Court’s ruling in Worcester v. Georgia (1832) affirming Cherokee sovereignty, Jackson famously defied the decision, stating, "John Marshall has made his decision; now let him enforce it." The Indian Removal Act of 1830 authorized the President to negotiate treaties for the removal of tribes from their eastern lands to territories west of the Mississippi. When negotiations failed or resistance arose, the US Army was dispatched to enforce these policies. The most infamous example is the "Trail of Tears" (1838-1839), where approximately 16,000 Cherokee, along with thousands of Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole people, were forcibly marched westward. Under the command of General Winfield Scott, some 7,000 soldiers oversaw the eviction, leading to the deaths of thousands from disease, starvation, and exposure. The army, in this instance, acted not as a combatant in a traditional war, but as an instrument of federal policy, executing a forced demographic cleansing.

As the nation expanded westward in the mid-19th century, particularly after the Mexican-American War and the California Gold Rush, the scale and intensity of conflict with Native Americans dramatically increased. The vast plains and mountains of the American West were home to powerful, nomadic tribes like the Lakota, Cheyenne, Arapaho, Comanche, and Apache, whose way of life was intrinsically linked to the buffalo and open spaces. The arrival of miners, ranchers, and homesteaders, coupled with the construction of transcontinental railroads, inevitably led to clashes over resources and territory.

The post-Civil War era saw the US Army, now a seasoned fighting force, turn its full attention to the "Indian problem." Generals William Tecumseh Sherman and Philip Sheridan, veterans of total war against the Confederacy, applied similar brutal tactics to the Plains Wars. Their strategy was often one of attrition and psychological warfare: destroy the Native Americans’ means of subsistence, particularly the buffalo, and relentless pursuit, especially during winter months when tribes were most vulnerable. Sheridan famously (and controversially) stated, "The only good Indian is a dead Indian," a sentiment that, whether directly uttered or not, encapsulated the prevailing military attitude towards Native resistance.

The plains became a crucible of conflict, marked by both strategic military victories and horrific massacres. The Sand Creek Massacre in 1864, where Colorado Volunteers under Colonel John Chivington attacked a peaceful Cheyenne and Arapaho village, killing over 150 men, women, and children, served as a stark example of the brutality inflicted upon Native populations. Conversely, Native American forces also achieved significant victories, none more famous than the Battle of the Little Bighorn in 1876, where a coalition of Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapaho warriors, led by figures like Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse, annihilated Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer’s 7th Cavalry detachment. This stunning defeat shocked the nation and only intensified the military’s resolve to crush Native resistance.

The army’s role in this period was multi-faceted: it protected the Bozeman Trail and other settler routes, guarded railroad construction crews, enforced treaty boundaries (often after those treaties had been broken by American expansion), and conducted punitive expeditions against tribes that resisted relocation to reservations or raided settlements. The destruction of the buffalo, a deliberate military strategy, decimated the Plains tribes’ primary food source, shelter, and cultural foundation, effectively forcing them into dependency on federal rations and life on reservations. "The buffalo are disappearing rapidly," Sherman wrote in 1868, "and with their disappearance the Indians must change their habits or starve." This was not merely an observation but a policy objective.

By the late 19th century, the era of open warfare was drawing to a close. Most Native American nations had been confined to reservations, their traditional ways of life shattered. Yet, resistance continued in new forms, notably the Ghost Dance movement, a spiritual revival that promised a return to ancestral lands and the disappearance of white settlers. Fearing a resurgence of hostilities, the US Army moved to suppress the movement. The tragic culmination came at Wounded Knee Creek, South Dakota, on December 29, 1890. The 7th Cavalry, Custer’s old regiment, attempting to disarm a band of Miniconjou Lakota under Chief Spotted Elk (Big Foot), opened fire with rifles and Hotchkiss guns. Between 250 and 300 Lakota, mostly unarmed men, women, and children, were killed. Twenty-five soldiers also died, many from friendly fire. Wounded Knee, described by some as a battle and by others as a massacre, effectively marked the end of major armed conflict between the US Army and Native Americans.

The legacy of the US Army’s involvement in Native American conflicts is profound and enduring. It was an instrument of national expansion, tasked with securing territory and enforcing federal policy, often in direct opposition to the rights and survival of indigenous peoples. The conflicts resulted in the catastrophic loss of life, land, culture, and sovereignty for Native American nations. The army’s actions, from forced removals to devastating military campaigns and massacres, inflicted deep, generational trauma that continues to impact Native communities today.

While the army’s role was often framed in the context of "civilizing" the frontier or protecting settlers, historical reassessment reveals a more nuanced and often brutal reality. The conflicts were not simply wars of conquest but often campaigns of ethnic cleansing, designed to clear the path for American Manifest Destiny. Understanding this complex history is crucial for a complete picture of the United States’ formation and its ongoing relationship with its indigenous populations. The shield and sword of the US Army, while building one nation, simultaneously dismantled many others, leaving an indelible mark on the American conscience and landscape.