Echoes of Ages, Wisdom for Tomorrow: The Indispensable Role of Traditional Ecological Knowledge in the 21st Century

In an era defined by accelerating environmental crises – a rapidly warming planet, unprecedented biodiversity loss, and the relentless degradation of ecosystems – humanity finds itself at a critical juncture. The scientific community issues increasingly dire warnings, and technological solutions are fervently sought. Yet, amidst this urgent quest for answers, a profound wellspring of wisdom, honed over millennia and deeply rooted in observation and respect for the natural world, often remains overlooked: Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK).

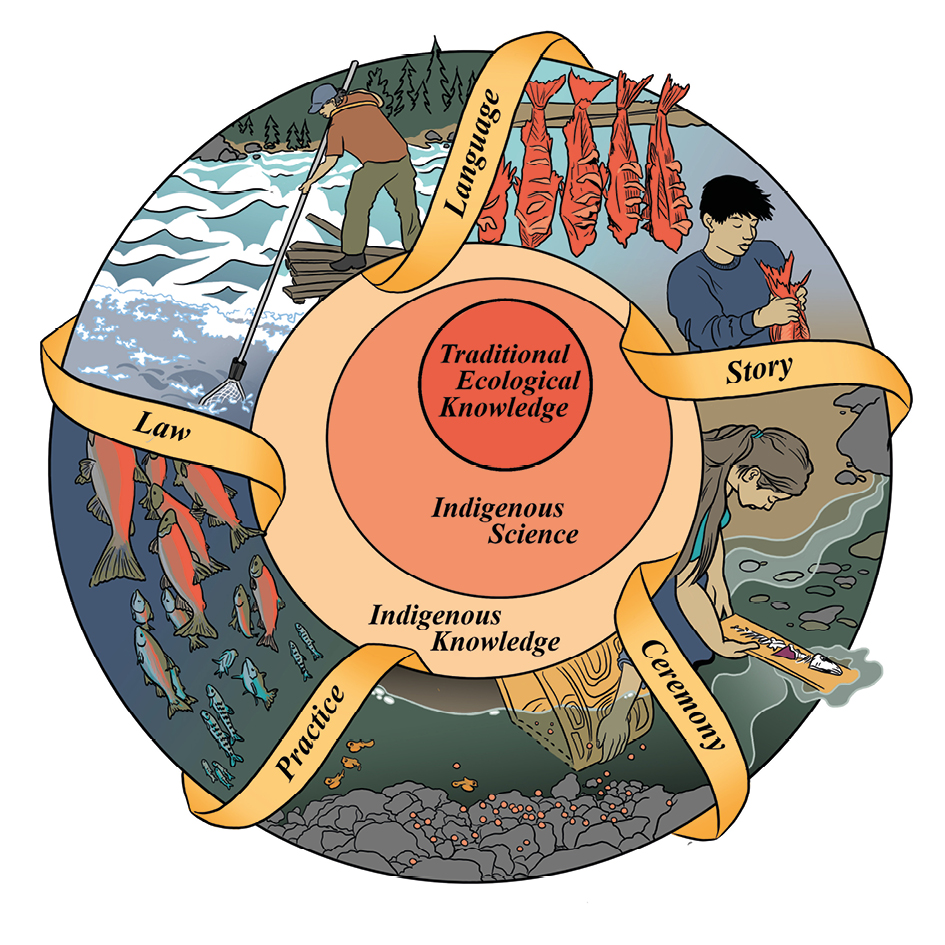

TEK, also known as Indigenous Knowledge (IK), is not merely a collection of facts or anecdotes. It is a cumulative body of knowledge, practice, and belief, evolving by adaptive processes and handed down through generations by cultural transmission, about the relationship of living beings (including humans) with one another and with their environment. It is holistic, encompassing spiritual, social, cultural, and political dimensions, inextricably linked to language, land, and identity. For countless Indigenous communities worldwide, this knowledge has been the bedrock of their survival, resilience, and harmonious coexistence with nature. Today, as the planet grapples with the consequences of an unsustainable trajectory, the indispensable role of TEK is gaining recognition as a vital, often untapped, resource for navigating the complex challenges of the 21st century.

A Legacy of Observation and Adaptation

What makes TEK so potent in our current predicament? Unlike the relatively short timescales of Western scientific study, TEK represents thousands of years of continuous observation, experimentation, and adaptation within specific ecological contexts. Indigenous peoples have lived intimately with their local environments, understanding nuanced patterns of weather, animal migrations, plant cycles, and soil dynamics in ways that modern science is only beginning to comprehend or replicate.

Consider the example of fire management. For decades, Western approaches in places like Australia and North America emphasized fire suppression, leading to an accumulation of fuel and, ultimately, more destructive mega-fires. In contrast, Aboriginal Australians have practiced "cool burning" for millennia – strategically lighting small, controlled fires at specific times of the year. This practice clears undergrowth, promotes biodiversity, and prevents catastrophic blazes. Recent collaborations between Indigenous fire practitioners and government agencies have demonstrated the profound effectiveness of this TEK, leading to significant reductions in both the frequency and intensity of bushfires, protecting lives, property, and ecosystems.

Similarly, in the Arctic, Inuit communities possess an intricate understanding of sea ice, weather patterns, and wildlife behaviour – knowledge vital for safe travel, hunting, and understanding environmental change. Their observations, often passed down through oral traditions, provide a long-term baseline for monitoring climate impacts that complements and often predates scientific data. This "Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit" (IQ) is proving invaluable in tracking the rapid transformations occurring in the polar regions.

Biodiversity Conservation: Guardians of the Earth

Indigenous peoples inhabit and manage an estimated 80% of the world’s remaining biodiversity, often in areas of critical ecological importance. Their knowledge is deeply embedded in conservation practices. The concept of "Kaitiakitanga" in Māori culture, for instance, embodies guardianship and stewardship of the natural environment, emphasizing the interconnectedness of all living things and the responsibility to protect them for future generations. This worldview often translates into sustainable resource management practices, such as rotational hunting or fishing, selective harvesting, and the protection of sacred sites that serve as de facto conservation zones.

"Indigenous knowledge offers profound insights into how to live sustainably with the land," says Dr. Fikret Berkes, a leading scholar on TEK. "It’s not just about what to do, but how to think about our relationship with nature." This ethical framework, rooted in reciprocity and respect, contrasts sharply with anthropocentric views that often underpin industrial resource extraction. Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas (IPCAs) are emerging globally as powerful models for conservation, where Indigenous communities lead the design and implementation of protection strategies, integrating their traditional laws, governance systems, and knowledge into modern conservation efforts. Canada, for example, is increasingly recognizing and supporting IPCAs as a key component of its national conservation targets.

Climate Change Adaptation and Mitigation

The wisdom contained within TEK is proving critical for both adapting to and mitigating the effects of climate change. Indigenous communities, often on the front lines of environmental shifts, are already employing traditional strategies to cope. This includes:

- Diverse Crop Varieties: Many Indigenous communities cultivate a wide array of resilient, locally adapted food crops that can withstand changing climate conditions, offering a critical safeguard against food insecurity. The Andean potato varieties, for example, are a testament to millennia of selective breeding for diverse conditions.

- Water Management: Traditional irrigation systems, water harvesting techniques, and the understanding of hydrological cycles in arid or semi-arid regions offer sustainable alternatives to large-scale, often environmentally damaging, modern infrastructure.

- Early Warning Systems: Indigenous knowledge of local indicators – changes in plant flowering, animal behaviour, or weather patterns – can provide early warnings of environmental shifts, allowing communities to adapt more quickly than external monitoring systems.

- Ecosystem Restoration: Traditional practices often focus on restoring ecosystem health, such as planting specific native species that stabilize soil, purify water, or attract beneficial wildlife, thereby enhancing resilience to climate impacts.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the leading international body for assessing climate change, has increasingly acknowledged the importance of Indigenous knowledge, integrating it into its assessments and emphasizing its role in adaptation and mitigation strategies. This marks a significant shift from past scientific paradigms that often overlooked or dismissed such knowledge.

Bridging the Divide: Synergy with Western Science

For too long, TEK was marginalized or dismissed as unscientific by Western paradigms. However, a growing recognition of its value has led to a push for the co-production of knowledge – a collaborative approach where Indigenous knowledge holders and Western scientists work together, respecting each other’s methodologies and insights.

This synergy offers immense potential. Western science can provide tools for large-scale data collection, modelling, and analysis, while TEK offers a depth of local understanding, long-term observational data, and a holistic perspective often missing from purely scientific approaches. For example, satellite imagery can track deforestation, but Indigenous knowledge can explain why certain areas are cleared, the history of land use, and the social dynamics involved – information crucial for effective conservation.

"Our knowledge is not just about what we know, but how we relate to the land, how we respect it," says Elder Dave Courchene Jr. of the Anishinaabe Nation. "It’s a spiritual relationship that teaches us responsibility. Western science can measure, but it often misses the heart."

Challenges and the Path Forward

Despite its immense value, TEK faces significant threats. Colonialism, forced assimilation, land dispossession, and the erosion of Indigenous languages and cultures have led to a tragic loss of this intergenerational wisdom. As elders pass away, their invaluable knowledge risks being lost forever. Furthermore, the commercial exploitation of traditional knowledge without free, prior, and informed consent (biopiracy) remains a serious concern, undermining the rights and sovereignty of Indigenous communities.

To truly harness the power of TEK, several actions are critical:

- Empowerment and Self-Determination: Indigenous communities must have the autonomy and resources to govern their lands and knowledge systems according to their own protocols and values.

- Respect and Reciprocity: Any engagement with TEK must be based on genuine respect, equitable partnerships, and a commitment to reciprocity, ensuring that Indigenous communities benefit from the sharing of their knowledge.

- Protection of Rights: Strong legal frameworks are needed to protect Indigenous intellectual property rights and prevent biopiracy.

- Language and Cultural Revitalization: Supporting Indigenous languages and cultural practices is essential, as TEK is deeply embedded within these traditions.

- Education and Awareness: Integrating TEK into educational curricula and public discourse can foster greater understanding and appreciation for its value.

In conclusion, as humanity confronts the profound environmental and social crises of the 21st century, the wisdom contained within Traditional Ecological Knowledge offers not just alternative perspectives, but often proven, sustainable pathways forward. It is a testament to resilience, a blueprint for living in harmony with the Earth, and a powerful reminder that the solutions to our most pressing global challenges may lie not in inventing entirely new technologies, but in listening, learning, and collaborating with those who have always understood the intricate language of the land. Embracing TEK is not just an act of justice for Indigenous peoples; it is an imperative for the survival and well-being of all.