The Double-Edged Pelt: How the Fur Trade Reshaped Early Native American History

For centuries, before the arrival of Europeans, the vast North American continent teemed with life, and its Indigenous peoples lived in intricate harmony with their environments. Their economies were built on subsistence, communal sharing, and reciprocal relationships, often involving localized trade of goods like obsidian, copper, shells, and agricultural products. Then came the fur trade, a phenomenon that would, within a few generations, irrevocably alter the social, economic, political, and environmental landscape of Native American societies, leaving a legacy that continues to resonate today. More than mere commerce, the fur trade was a catalyst, a double-edged pelt that brought both unprecedented opportunity and devastating upheaval.

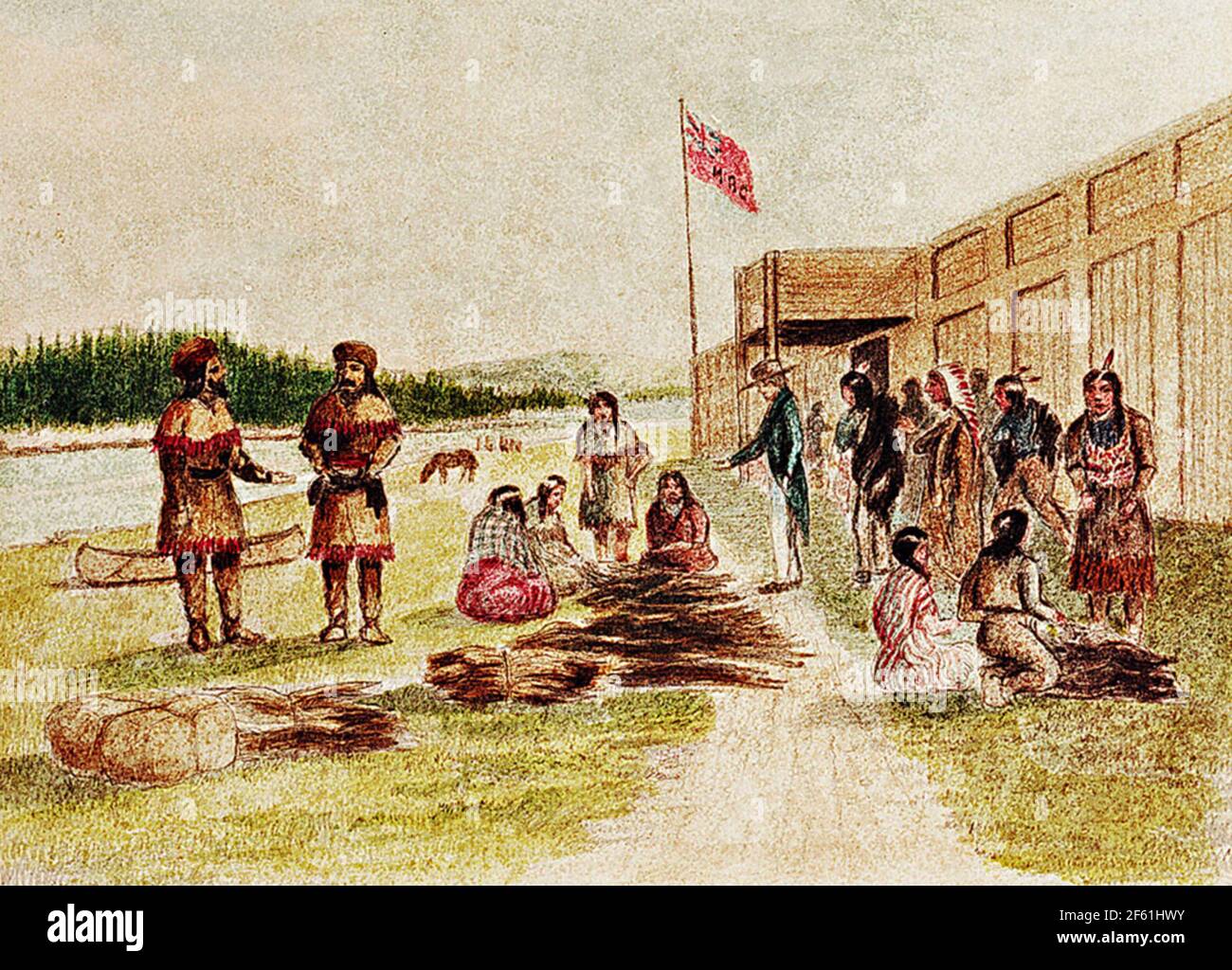

The allure of North American furs, particularly beaver, was immense for European markets. The burgeoning fashion industry in Europe, especially for felt hats, created an insatiable demand for beaver pelts, which were superior for felting than European varieties. What began with initial, often tentative exchanges between Indigenous peoples and European explorers in the 16th century—a few trinkets for valuable furs—quickly escalated into a sophisticated, continent-spanning economic system. The French, Dutch, English, and later the Spanish, all vied for control of these lucrative networks, establishing trading posts that became magnets for Indigenous communities.

Economic Transformation: From Subsistence to Market

Perhaps the most immediate and profound impact of the fur trade was the radical transformation of Native American economies. Traditionally, hunting was for sustenance, and trade was for goods not locally available. The fur trade introduced a market economy driven by profit and external demand. Indigenous hunters, who possessed unmatched knowledge of the land and its animal populations, found themselves in a new role: suppliers to a global market.

"The introduction of European trade goods fundamentally shifted Indigenous priorities," notes historian Daniel Richter in Facing East from Indian Country. "Suddenly, a good hunting season meant not just food and clothing for the winter, but also highly coveted metal tools, firearms, and blankets." Metal axes and knives, superior to traditional stone tools, made tasks like felling trees and butchering animals significantly easier. Iron pots replaced fragile pottery, making cooking more efficient. Firearms, initially a novelty, quickly became essential for hunting, warfare, and asserting tribal dominance. These goods were not just conveniences; they became necessities, creating a deep dependency on European suppliers.

This dependency, however, came at a cost. As Native communities focused more on trapping furs for trade, their traditional subsistence activities sometimes suffered. Time spent hunting beaver for pelts was time not spent growing corn or hunting deer for food. Furthermore, the European traders often introduced the concept of credit, drawing Indigenous hunters into cycles of debt that further bound them to the trading posts and their European partners.

Social and Political Reshaping: Alliances, Conflicts, and Shifting Power

The economic shifts brought by the fur trade rippled through the social and political structures of Native American societies. Tribes strategically positioned near trading posts, or those with access to rich hunting grounds, saw their power and influence grow. They became "middlemen," controlling access to European goods for their interior neighbors, thereby accumulating wealth and prestige.

This new dynamic fueled intense inter-tribal rivalries and warfare. The "Beaver Wars" of the 17th century, primarily involving the Iroquois Confederacy against Algonquin-speaking tribes and their French allies, are a stark example. Driven by the depletion of beaver populations in their own territories and the desire to control new hunting grounds and trade routes, the Iroquois launched devastating campaigns, acquiring firearms from their Dutch and later English allies. These wars decimated entire communities, displaced populations, and redrew the ethnographic map of the Northeast. The scale and intensity of these conflicts were unprecedented, largely driven by the demand for pelts and the acquisition of European weaponry.

Within communities, the fur trade also altered traditional gender roles. While men became the primary hunters and trappers, women’s roles in processing hides—scraping, tanning, and preparing them for market—became crucial to the economic success of the family and tribe. In some cases, this enhanced their economic importance; in others, as the focus shifted to commodity production, it could lead to increased workload without commensurate recognition, or even a devaluation of other traditional female roles. Marriage alliances between Indigenous women and European traders, often called mariage à la façon du pays (marriage according to the custom of the country), also became common, serving to cement trade relationships and integrate traders into Indigenous social networks, though these unions also carried complex social implications.

Environmental Consequences: The Price of Pelts

The relentless pursuit of furs had catastrophic environmental consequences. Indigenous hunting practices, traditionally geared towards sustainable yields and respect for the natural world, were often overwhelmed by the demands of the European market. Beaver, otter, deer, and other fur-bearing animals were hunted to near-extinction in many regions.

The ecological impact was profound. Beaver, as a keystone species, played a crucial role in shaping aquatic ecosystems through their dam-building activities, which created wetlands, regulated water flow, and supported diverse plant and animal life. Their widespread eradication led to significant changes in water tables, stream morphology, and biodiversity across vast swathes of the continent. The loss of these animals wasn’t just an economic blow; it was an ecological disaster, fundamentally altering the landscapes Native peoples had known for millennia.

Cultural Exchange and Erosion: A Blended Reality

Beyond economics and politics, the fur trade facilitated a complex cultural exchange. Indigenous peoples adopted European technologies and goods, which in turn influenced their material culture, art forms, and even spiritual beliefs. Glass beads, for instance, were incorporated into traditional beadwork, creating new aesthetic expressions. European blankets replaced animal hides, and cloth found its way into traditional garments.

However, this exchange was not always benign. Alcohol, a particularly insidious trade item, was often introduced by traders, sometimes intentionally to gain an advantage in negotiations. Its devastating effects on individuals and communities contributed to social disruption, health problems, and the erosion of traditional social controls. Missionaries, often accompanying traders, also sought to convert Indigenous peoples, challenging traditional spiritual beliefs and practices. While some Indigenous communities selectively adopted aspects of Christianity, others fiercely resisted, leading to cultural clashes and internal divisions.

The Inevitable Slide: From Trade Partners to Land Loss

Perhaps the most tragic long-term consequence of the fur trade was its role in paving the way for European colonial expansion and subsequent land dispossession. Initially, Europeans viewed Native Americans as essential trade partners, crucial to their economic success in the New World. This relationship, while unequal, afforded Indigenous nations a degree of leverage and recognition of their sovereignty. Treaties were signed, alliances forged, and boundaries acknowledged.

However, as the fur resources dwindled in eastern regions, and as European populations grew, the colonial powers’ priorities shifted from trade to settlement. The land itself, not just its resources, became the ultimate prize. The dependency on European goods, the decimation of fur-bearing animals, and the weakening of some tribes through warfare and disease, left many Native American nations vulnerable. The transition from valuable trade partners to obstacles to agricultural expansion was gradual but inexorable. The very trails and waterways that had been vital for the fur trade later became routes for settlers and soldiers, leading to further encroachment and conflict.

A Complex and Enduring Legacy

The role of the fur trade in early Native American history is a testament to the complex, often contradictory, forces that shaped the continent. It was a period of unprecedented economic opportunity, technological advancement, and cultural exchange. It also brought about devastating wars, ecological destruction, disease, social disruption, and ultimately, laid the groundwork for the loss of land and sovereignty that would define Native American experiences for centuries to come.

To view the fur trade as simply a transaction misses its profound, transformative power. It was an engine of globalization before the term existed, connecting distant continents and cultures, and fundamentally reshaping the lives of millions. The legacy of the fur trade is not one of simple good or evil, but a deeply interwoven tapestry of opportunity and despair, resilience and adaptation, whose threads continue to be felt in Indigenous communities across North America today. It stands as a powerful reminder of how external forces, driven by economic demand, can fundamentally alter the course of human societies and their relationship with the natural world.