The Paved Path to Extinction: Turtle Road Mortality on Turtle Island

On Turtle Island, the vast landmass North America’s Indigenous peoples call home, the ancient journey of turtles has taken a perilous turn. For millennia, these slow-moving reptiles, symbols of wisdom, endurance, and creation in many Indigenous cultures, have navigated landscapes shaped by nature. Today, their ancestral paths are bisected by an ever-expanding network of asphalt and concrete, transforming vital movements into a deadly gamble. Road mortality has emerged as a leading, and increasingly devastating, threat to turtle populations across Canada, the United States, and Mexico, pushing many species toward the brink of extinction.

The problem is stark. Each year, countless turtles are crushed under the wheels of vehicles, their hard shells offering no defense against tons of speeding metal. This isn’t merely an unfortunate accident; it’s a systemic ecological crisis. Turtles, particularly freshwater and terrestrial species, are inherently vulnerable to roads due to their life history traits. They are long-lived, slow to mature, and have low reproductive success rates. A female turtle might not lay her first clutch of eggs until she is 10, 15, or even 20 years old. Once mature, she may only produce a small number of eggs annually, many of which will fall victim to predators or environmental factors. The loss of even a single adult female, therefore, represents a significant blow to a population, effectively erasing decades of potential reproductive output.

"For most turtle species, the loss of just two or three adult females per year from a local population can lead to its eventual collapse," explains Dr. Vivianne Lapierre, a conservation biologist specializing in herpetology. "They simply cannot reproduce fast enough to offset the mortality rates we see on our roads. It’s a demographic death sentence."

Turtles cross roads for a myriad of reasons, all rooted in their fundamental biological needs. Spring and early summer are particularly deadly. Females, driven by an ancient instinct, emerge from wetlands and forests in search of suitable nesting sites – typically sandy, well-drained areas with good sun exposure. Often, the ideal spot lies just across a busy highway from their home pond. Males also cross roads in search of mates, and both sexes may move between different habitats to forage, bask, or overwinter. Habitat fragmentation, where natural areas are broken up by human development, intensifies this problem, forcing turtles to traverse dangerous corridors to access essential resources that were once part of a continuous landscape.

The scale of the problem is immense. While precise numbers are difficult to quantify across the entire continent, localized studies paint a grim picture. In some regions, road mortality accounts for over 80% of adult turtle deaths. Species like the Blanding’s Turtle, Wood Turtle, Spotted Turtle, and Snapping Turtle, all of which are listed as endangered, threatened, or of special concern in various parts of their range, are disproportionately affected. Their slow movements and reluctance to abandon a chosen path make them easy targets. The common Painted Turtle, while still widespread, also suffers significant losses, which over time could lead to localized declines.

Beyond direct mortality, roads pose other, more insidious threats. They act as barriers, preventing genetic exchange between isolated populations and leading to inbreeding and reduced genetic diversity. They introduce pollutants, alter hydrology, and create edge effects that expose turtles to increased predation. The sheer noise and vibration can also stress wildlife, disrupting natural behaviors.

The Indigenous understanding of turtles adds another layer of urgency to this crisis. In many origin stories, Turtle Island itself was formed on the back of a giant turtle. The turtle represents the Earth, resilience, and the interconnectedness of all life. To witness their decline on such a scale is not just an ecological tragedy, but a cultural and spiritual wound.

"The turtle is our elder, our teacher," says Elder Mary Lou Fox, an Anishinaabe knowledge keeper. "They carry the stories of creation on their backs. When we see them broken on the road, it’s a sign that something is deeply out of balance. We are losing not just a species, but a piece of our history, our identity, and the wisdom they hold for us." This perspective emphasizes the moral imperative to protect turtles, not just for their ecological role, but for their intrinsic value and cultural significance.

Recognizing the severity of the situation, conservationists, government agencies, Indigenous communities, and citizen scientists are mobilizing to find solutions. These efforts range from low-tech interventions to sophisticated engineering projects:

-

Wildlife Crossings and Exclusion Fencing: The most effective long-term solution involves creating safe passage for turtles. This includes installing specialized culverts, tunnels, or ecobridges beneath or over roads, coupled with exclusion fencing that funnels turtles towards these safe crossing points. Studies have shown properly designed and maintained systems can significantly reduce road mortality, often by 80-90% for some species. However, these projects are expensive and require careful planning to match turtle movement patterns.

-

Public Awareness and Education: Campaigns to educate drivers about turtle crossing seasons, the importance of slowing down, and how to safely assist a turtle across the road are crucial. Many conservation groups provide guidelines on how to move a turtle (always in the direction it was headed, and only if it’s safe for the helper).

-

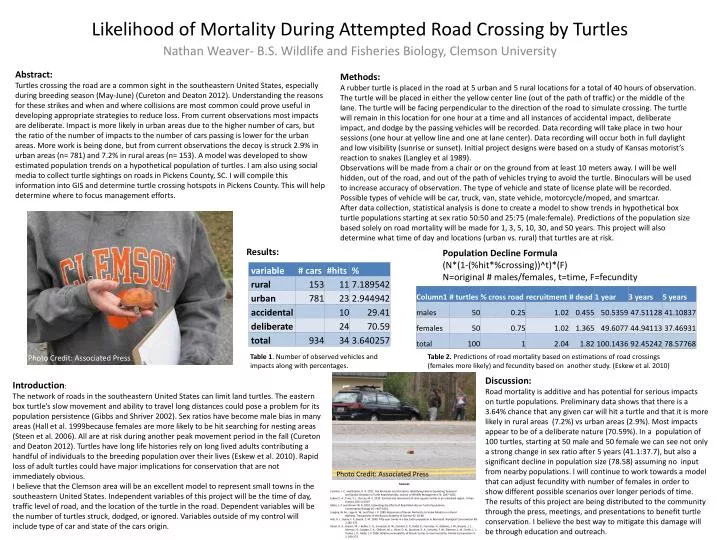

Citizen Science and Data Collection: Programs like "Turtle Patrols" and online reporting tools allow volunteers to record road mortality incidents. This data is vital for identifying hotspots, understanding movement patterns, and informing where mitigation efforts are most needed. Knowing where and when turtles are most vulnerable is the first step towards targeted action.

-

Habitat Restoration and Management: Protecting and restoring adjacent habitats reduces the need for turtles to cross roads. This includes managing water levels, controlling invasive species, and creating suitable nesting sites away from high-traffic areas.

-

Temporary Signage: During peak migration and nesting seasons, temporary road signs alerting drivers to turtle crossings can be effective in high-risk areas.

-

Indigenous-led Conservation: Many Indigenous communities are at the forefront of turtle conservation, integrating traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) with Western science. Their deep understanding of local ecosystems and long-standing stewardship practices offer invaluable insights into effective conservation strategies. These initiatives often focus on habitat protection, cultural education, and community engagement.

Despite these efforts, significant challenges remain. The sheer vastness of Turtle Island’s road network, coupled with limited funding and political will, makes implementing solutions at scale a monumental task. Climate change further complicates matters, altering habitats and potentially shifting turtle movement patterns in unpredictable ways.

The future of turtles on Turtle Island hangs precariously in the balance. Their ancient journeys, once dictated by the rhythms of nature, are now dictated by the geometry of human infrastructure. Protecting these iconic reptiles requires a fundamental shift in our relationship with the land – one that prioritizes coexistence and recognizes the profound ecological and cultural value of every living being. It demands a collective effort: from individual drivers who slow down and safely assist a turtle, to policymakers who fund wildlife crossings, to Indigenous communities who continue to share their wisdom and stewardship. Only then can we hope to ensure that the turtle continues its slow, resilient journey, carrying the weight of the world and the hope of a balanced future, for generations to come. The paved path doesn’t have to be a path to extinction; it can, with conscious effort, become a bridge to survival.