Invisible Wounds, Visible Disparities: The Urgent Research into Native American Health Equity

In the heart of one of the world’s wealthiest nations, a profound health crisis casts a long shadow over Native American communities. While often overlooked by mainstream discourse, the disparities in health outcomes for Indigenous peoples in the United States are not merely statistical anomalies; they are the enduring legacy of centuries of systemic oppression, cultural erasure, and broken promises. Understanding these disparities, and crucially, finding equitable solutions, is the urgent task of contemporary health research, a field grappling with historical mistrust and the imperative of genuine community partnership.

The statistics paint a grim picture. Native Americans experience significantly higher rates of chronic diseases, mental health challenges, and lower life expectancies compared to the general U.S. population. For instance, the life expectancy for Native Americans is often 5 to 10 years lower than for other Americans. They are nearly three times more likely to be diagnosed with diabetes, face disproportionately high rates of heart disease, cancer, and stroke, and struggle with mental health issues, including suicide, at rates far exceeding national averages, particularly among youth. These are not just health problems; they are social justice issues, rooted deeply in the historical and ongoing social determinants of health.

Echoes of History: The Roots of Disparity

To comprehend the current health landscape, one must look back. The forced removal from ancestral lands, the decimation of populations through disease and violence, and the deliberate policies of cultural assimilation – perhaps most infamously embodied by the Indian boarding school system – have left an indelible scar. These historical traumas are not confined to history books; they manifest as intergenerational trauma, impacting mental health, parenting practices, and the very fabric of community well-being.

Dr. Maria Yellow Horse Brave Heart, a Hunkpapa Lakota social worker and academic, is a pioneer in the concept of historical trauma, defining it as "the cumulative emotional and psychological wounding over the lifespan and across generations, emanating from massive group trauma." This trauma directly contributes to the higher rates of substance abuse, depression, and suicide seen in Native communities today. Research into these connections is vital, not just to document the pain, but to inform culturally resonant healing strategies that acknowledge and address these deep wounds.

Furthermore, broken treaties and chronic underfunding of essential services have crippled tribal nations’ ability to provide for their own. The Indian Health Service (IHS), established by treaty obligations to provide healthcare to federally recognized tribes, is notoriously underfunded. A 2018 report by the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights found that IHS per capita spending was significantly lower than other federal health programs, leading to inadequate facilities, staff shortages, and limited access to specialized care. This creates what many refer to as "healthcare deserts" on reservations, forcing individuals to travel hundreds of miles for basic medical attention, if they can access it at all.

Social Determinants: A Web of Disadvantage

Beyond historical trauma and systemic underfunding, a complex web of social determinants of health disproportionately affects Native American communities. Poverty is rampant, with many reservations facing unemployment rates far exceeding the national average. This leads to food insecurity, limited access to nutritious food (often relying on expensive, processed options from distant stores), and substandard housing.

- Poverty and Food Insecurity: The lack of economic opportunity often translates into "food deserts," where fresh produce and healthy options are scarce or unaffordable. This contributes directly to high rates of diabetes and obesity. Research exploring community-led food sovereignty initiatives – reclaiming traditional agricultural practices and local food systems – offers promising avenues for intervention.

- Education: Disparities in educational attainment limit opportunities for stable employment and higher income, perpetuating the cycle of poverty. Educational attainment is strongly correlated with health outcomes.

- Housing and Infrastructure: Many tribal communities lack basic infrastructure, including clean water, reliable sanitation, and adequate housing. Overcrowding and exposure to environmental hazards, such as abandoned uranium mines on Navajo lands, contribute to respiratory illnesses, cancer, and other chronic conditions.

- Environmental Justice: Native American lands are often targeted for polluting industries, from fossil fuel extraction to waste disposal, exposing communities to toxins that impact air and water quality. Research in environmental health disparities is crucial to document these impacts and advocate for protective policies.

The Evolving Role of Research: From Exploitation to Partnership

The relationship between academic research and Native American communities has historically been fraught with mistrust, and for good reason. Past research has often been extractive, exploiting Indigenous knowledge and biological samples without informed consent, fair compensation, or benefit to the communities themselves. The infamous Havasupai Tribe case, where DNA samples collected for diabetes research were later used for studies on schizophrenia and inbreeding without the tribe’s permission, serves as a stark reminder of these ethical breaches.

This history has led to a crucial paradigm shift in how research is conducted. The concept of data sovereignty has emerged, asserting that Indigenous nations have the right to own, control, access, and possess their own data. This is not just about ethical practice; it’s about empowering communities to define their own research priorities, participate in data collection and analysis, and ensure that findings directly benefit their people.

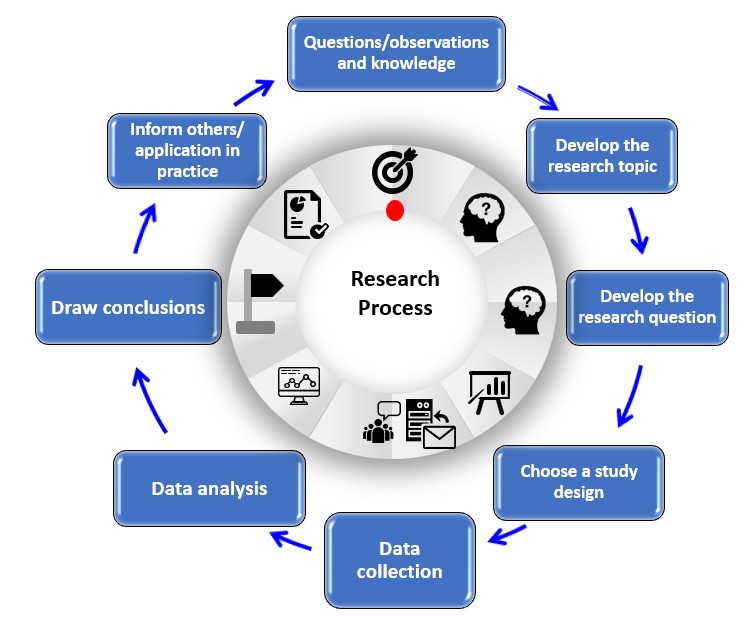

Community-Based Participatory Research (CBPR) has become the gold standard. In CBPR, researchers work in genuine partnership with communities, sharing power and decision-making throughout the entire research process. This approach builds trust, ensures cultural relevance, and produces more impactful and sustainable interventions. For example, research into diabetes prevention might involve traditional healers, elders, and community health workers in designing interventions that incorporate traditional foods and physical activities, rather than simply imposing Western dietary guidelines.

Key Areas of Current Research:

- Mental Health and Trauma-Informed Care: Research is focusing on developing culturally specific interventions for historical trauma, suicide prevention, and substance abuse. This includes exploring the efficacy of traditional healing practices, culturally adapted cognitive-behavioral therapies, and community-led peer support programs.

- Chronic Disease Prevention and Management: Studies are examining effective strategies for diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer prevention, often integrating traditional knowledge, dietary practices, and physical activity. Research into genetic predispositions within Native populations, while sensitive, can also inform targeted prevention.

- Environmental Health: Investigating the health impacts of environmental pollution, climate change, and resource extraction on tribal lands, and supporting community-led advocacy for environmental justice.

- Access to Care and Health System Improvement: Research is crucial for evaluating the effectiveness of IHS and tribal health programs, identifying barriers to care, and developing policy recommendations for equitable funding and culturally competent healthcare delivery. This includes exploring telemedicine solutions for remote communities.

- Indigenous Resilience and Strengths: Moving beyond a deficit-based model, a growing body of research highlights the incredible resilience of Native American communities, their enduring cultural strengths, and the protective factors embedded in traditional practices, spiritual beliefs, and strong kinship ties. Understanding these assets is key to building effective health promotion strategies.

Looking Forward: A Path to Equity

The journey towards health equity for Native Americans is long and complex, but research, when conducted ethically and in true partnership, offers a powerful tool for change. It requires a commitment from institutions and individual researchers to:

- Respect Tribal Sovereignty: Recognize and uphold the inherent rights of tribal nations to govern their own affairs, including health and research.

- Prioritize Community Engagement: Ensure that research questions, methods, and dissemination strategies are co-created with and driven by Native communities.

- Invest in Indigenous Researchers: Support the development and training of Native American scientists and health professionals who can lead research that is culturally grounded and directly relevant to their people.

- Advocate for Policy Change: Translate research findings into actionable policy recommendations that address systemic inequalities, improve funding for tribal health systems, and protect environmental health.

- Acknowledge and Address Historical Injustice: Understand that health disparities are not random but are direct consequences of historical and ongoing injustices, requiring a commitment to reconciliation and restorative justice.

As Dr. Mary Bassett, a former New York City Health Commissioner and Harvard professor, once remarked, "Your zip code is a better predictor of your health than your genetic code." For Native Americans, this sentiment rings especially true, amplified by a history that has systematically disadvantaged entire populations. The urgent research into Native American health disparities is not merely an academic exercise; it is a moral imperative, a quest for justice, and a vital step towards honoring treaty obligations and building a healthier, more equitable future for all. It demands listening, learning, and above all, authentic partnership to heal the invisible wounds and rectify the visible disparities that have persisted for far too long.