Echoes of Earth and Spirit: The Enduring Legacy of New Mexico’s Pueblo Arts

In the sun-drenched landscapes of New Mexico, where ancient mesas meet vast skies, lies a vibrant tapestry woven from millennia of tradition, resilience, and profound spiritual connection to the land. This is the heartland of the Pueblo people, whose artistic expressions are not merely decorative objects but living narratives, prayers made tangible, and a continuous testament to an enduring culture. From the delicate lines of a black-on-black pot to the intricate turquoise inlay of a silver bracelet, Pueblo tribal arts are a powerful dialogue between the past and the present, inviting the world to listen.

The story of Pueblo art is as old as the Pueblo people themselves, stretching back thousands of years to the Ancestral Puebloans (often referred to as Anasazi). Their earliest artistic endeavors—petroglyphs carved into rock faces, rudimentary pottery, and woven baskets—were functional yet imbued with symbolic meaning. Over centuries, these foundational techniques evolved, adapting to new materials, influences, and environmental changes, yet always retaining a core reverence for the earth and its cycles.

Clay as a Canvas: The Soul of Pueblo Pottery

Perhaps the most iconic and globally recognized Pueblo art form is pottery. More than just vessels, Pueblo pots are expressions of identity, each piece bearing the distinct fingerprint of its maker and its pueblo of origin. The process itself is a sacred ritual, beginning with the gathering of clay from specific ancestral sites, often accompanied by prayers. The clay is then cleaned, mixed with temper (volcanic ash, ground up pot shards, or sand) to prevent cracking, and built up using the ancient coil method – a slow, meditative process that allows the potter to connect deeply with the material.

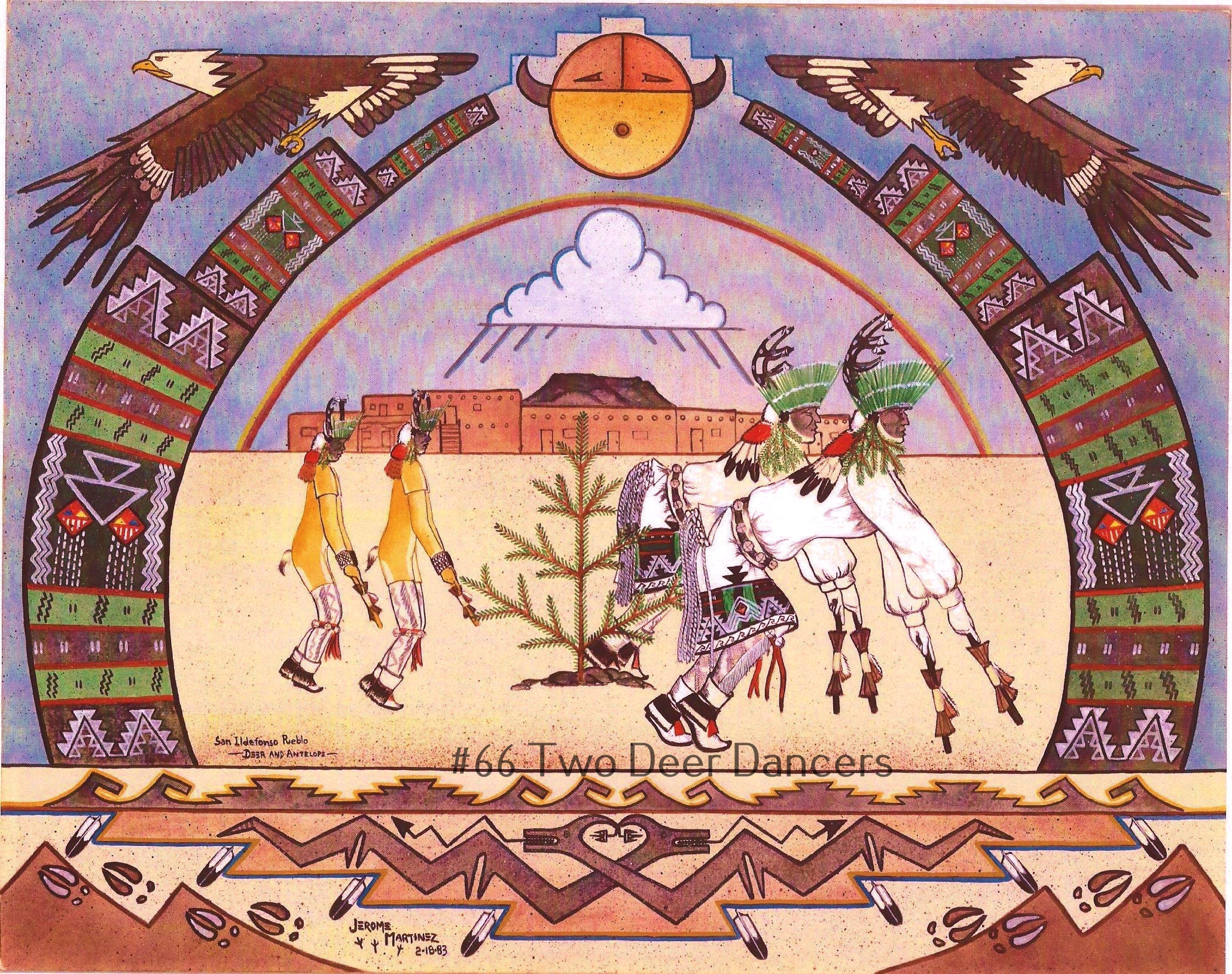

Firing is traditionally done outdoors, often in sheep dung or wood fires, producing the characteristic earthy tones and subtle variations that industrial kilns cannot replicate. The designs, painted with natural pigments derived from plants and minerals, are rich in symbolism: clouds for rain, feathers for prayer, corn for sustenance, and geometric patterns representing mountains, rivers, and the cosmos.

Each Pueblo has developed its own distinctive style. Acoma Pueblo, known as "Sky City" for its mesa-top location, produces exceptionally thin-walled, lightweight pottery adorned with fine-line geometric patterns, often in black and white, or black, white, and orange. Their olla (water jar) forms are celebrated for their elegant symmetry. Zuni Pueblo pottery, by contrast, is known for its heartline deer motif – a deer with an arrow extending from its mouth to its heart, symbolizing life and breath. Their polychrome designs are often bold and feature birds, frogs, and other animals.

The Tewa-speaking Pueblos of San Ildefonso and Santa Clara are famous for their polished blackware and redware. It was at San Ildefonso that the legendary potter Maria Martinez (c. 1887–1980) and her husband Julian revolutionized Pueblo pottery in the early 20th century. Rediscovering and perfecting the ancient black-on-black firing technique, they transformed utilitarian vessels into highly sought-after fine art. Maria’s polished surfaces and Julian’s matte designs created a striking contrast that captivated the art world, bringing international acclaim and economic vitality to her pueblo. Her work, and that of her descendants, continues to influence generations of potters.

A fascinating fact about Maria Martinez: She initially kept her specific black-on-black firing technique a secret to protect her pueblo’s economic advantage, only later sharing it with her community to ensure the tradition’s continuation.

Shimmering Stones and Silver: Pueblo Jewelry

While the Navajo are perhaps most famous for their silverwork, Pueblo jewelers have a distinct and equally rich tradition, often emphasizing intricate stonework and unique design elements. The introduction of silver by the Spanish and later refined by Navajo smiths was adopted by Pueblo artisans, who then integrated their own cultural aesthetics.

Turquoise, a stone deeply revered across the Southwest, holds immense spiritual significance for the Pueblo people, representing the sky, water, and healing. It is often combined with other natural materials like coral, shell (especially mother-of-pearl and abalone), and jet.

Zuni Pueblo jewelers are masters of lapidary work, renowned for their intricate channel inlay and needlepoint techniques. Channel inlay involves precisely cutting stones (often turquoise, coral, jet, and mother-of-pearl) to fit into silver channels, creating mosaic-like patterns. Needlepoint, on the other hand, features tiny, hand-cut stones, often set around a central larger stone, creating a delicate, lace-like effect. Their pieces frequently depict animal figures, particularly the fetish bear, symbolizing strength and healing.

Hopi Pueblo jewelers are known for their distinctive overlay technique. Two layers of silver are used: the top layer has a design cut out, and this is soldered onto a solid bottom layer. The recessed areas are then oxidized (blackened), creating a striking contrast that highlights the intricate designs, which often feature traditional Hopi motifs like the sun, corn, and cloud symbols.

For Pueblo people, jewelry is more than adornment; it is protection, a connection to the ancestors, and a display of spiritual wealth. "Every piece of turquoise tells a story," one Pueblo elder once said. "It carries the energy of the earth and the prayers of our people."

Spiritual Guardians: Kachina Dolls

While primarily associated with the Hopi and Zuni Pueblos, Kachina (or Katsina) dolls are a profound and sacred art form that embodies the spiritual essence of these cultures. These carved wooden figures are not toys, but sacred effigies representing the Katsinam – benevolent spiritual beings who act as intermediaries between humans and the divine, bringing rain, health, and fertility.

Carved from the root of the cottonwood tree, a water-loving plant that symbolizes life and growth in the arid Southwest, each Katsina doll is meticulously painted and adorned to represent a specific Katsina spirit, of which there are hundreds. From the powerful Eagle Katsina to the gentle Butterfly Katsina, each has its own distinct characteristics, songs, and dances performed during ceremonial cycles.

Katsina dolls are traditionally given to children, particularly girls, during ceremonial dances. They serve as educational tools, helping children learn about the various Katsinam, their attributes, and the moral lessons they embody. They are also considered representations of spiritual presence within the home, reminding families of their connection to the sacred. The artistry lies not just in the carving, but in the meticulous painting and the use of natural materials for adornment, such as feathers, shells, and fabric, all contributing to the authenticity and spiritual power of the figure.

Weaving, Drums, and the Living Tradition

Beyond pottery, jewelry, and Katsina dolls, Pueblo arts encompass a rich array of other forms. Weaving traditions, though often overshadowed by the Navajo, are deeply rooted in Pueblo culture, particularly among the Hopi, who are renowned for their intricate sashes, kilts, and blankets. The Rio Grande weaving tradition, a blend of indigenous and Spanish techniques, also saw Pueblo artisans creating distinctive striped blankets and utilitarian textiles.

Drum making is another vital art, with drums being central to ceremonial dances and music. Made from hollowed cottonwood logs and animal hides, each drum is a living instrument, its beat connecting the dancers to the heartbeat of the earth and the rhythm of ancestral prayers. Basketry, though less common today than in ancient times, remains a skill preserved in some Pueblos, with coiled and plaited baskets serving both practical and ceremonial purposes.

Art as Life, Life as Art: The Spiritual Core

What truly distinguishes Pueblo art is its intrinsic connection to daily life, spiritual belief, and community. Unlike Western art, which often separates aesthetics from utility, Pueblo art is almost always functional or ceremonial. A pot holds water or food; jewelry offers protection; a Katsina doll teaches spiritual lessons; a woven sash is worn in dance.

"For us, art is not separate from life; it is life itself," remarks a contemporary Pueblo potter. "Every design, every coil of clay, every stone set in silver, is a prayer, a connection to our ancestors, and an expression of our gratitude for the world around us." This deep philosophical underpinning means that the creation of art is often a meditative and prayerful act, imbuiling the finished piece with a spiritual resonance that transcends its material form.

Navigating Modernity: Innovation and Preservation

In the 21st century, Pueblo artists face the challenge and opportunity of navigating a rapidly changing world. While deeply committed to preserving ancient techniques and traditional designs, many contemporary artists are also innovating, blending ancestral forms with modern aesthetics, materials, and messages. Sculptors like Roxanne Swentzell (Santa Clara Pueblo) create powerful, expressive clay figures that explore themes of identity, humanity, and the environment, pushing the boundaries of traditional pottery while remaining rooted in her cultural heritage.

The economic impact of Pueblo arts is significant. Annual events like the Santa Fe Indian Market, organized by the Southwestern Association for Indian Arts (SWAIA), draw thousands of collectors, gallerists, and tourists, providing a vital marketplace for artists and showcasing the diversity and excellence of Native American art. These markets not only provide income but also serve as crucial platforms for cultural exchange and education.

However, challenges remain. Issues of cultural appropriation, ensuring authenticity in the market, and sustaining traditional knowledge among younger generations are ongoing concerns. Pueblo communities are actively engaged in preserving their artistic heritage through educational programs, apprenticeships, and cultural centers, ensuring that the ancient skills and stories continue to be passed down.

The Pueblo tribal arts of New Mexico are far more than beautiful objects. They are living archives of history, profound expressions of spirituality, and testaments to the enduring strength and creativity of a people deeply rooted in their land and traditions. Each piece tells a story, not just of its maker, but of a vibrant culture that continues to adapt, innovate, and thrive, its echoes resonating across the mesas and inspiring all who encounter them. To truly appreciate Pueblo art is to understand that it is not merely seen, but felt, a profound connection to the earth, the ancestors, and the enduring human spirit.