Pueblo Silversmithing: Tribal Jewelry Traditions and Artistic Innovations

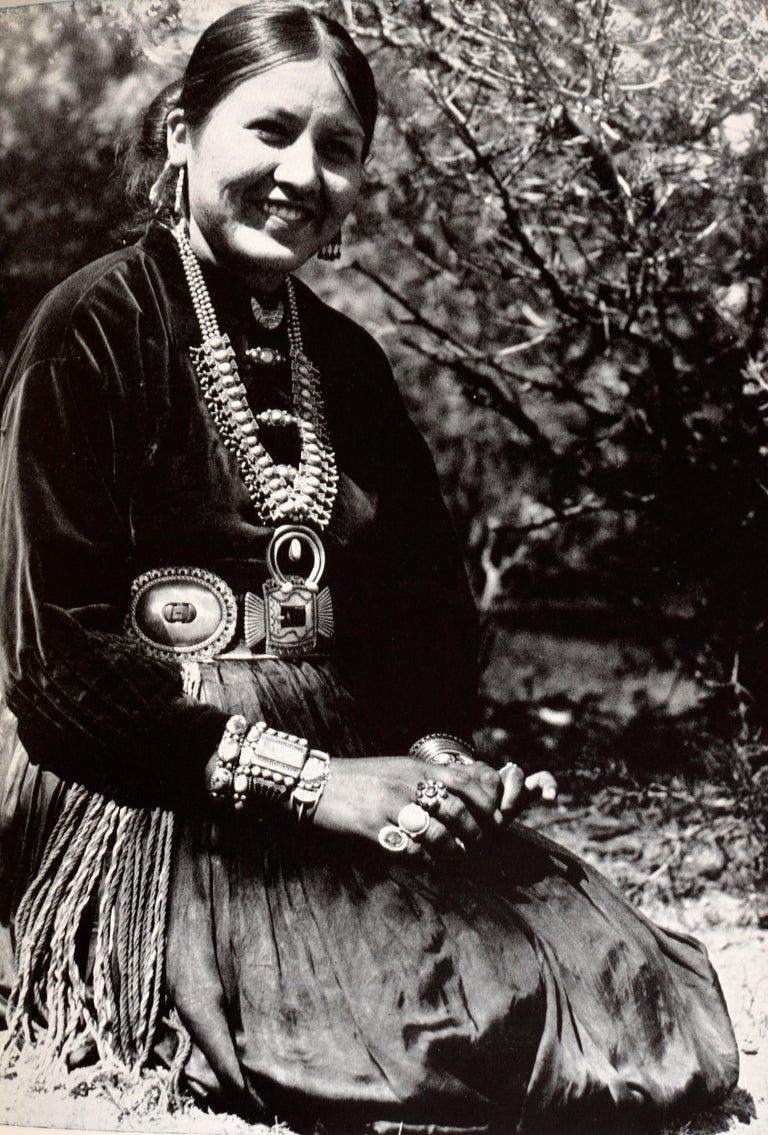

In the sun-drenched landscapes of the American Southwest, where ancient traditions intertwine with the rugged beauty of the land, a profound artistic legacy has flourished for centuries: Pueblo silversmithing. Far more than mere adornment, the intricate silver and stone jewelry crafted by the Pueblo peoples—the Zuni, Hopi, Kewa (Santo Domingo), and others—is a vibrant narrative woven from cultural identity, spiritual reverence, and an unwavering commitment to artistic excellence. From the subtle elegance of traditional designs passed down through generations to the bold statements of contemporary innovation, Pueblo jewelry stands as a testament to the enduring creativity and resilience of these sovereign nations.

The story of Pueblo silversmithing is one of adaptation and mastery, deeply rooted in pre-contact practices of adornment. Before the arrival of Europeans, Pueblo artisans adorned themselves with beads of shell, bone, seeds, and meticulously cut and polished turquoise, a stone revered for its spiritual significance and connection to water and sky. The Spanish introduction of silver and metalworking tools in the 17th century laid the groundwork for a new chapter, but it was the Navajo, learning from Mexican plateros in the mid-19th century, who first extensively adopted silversmithing in the region. The Pueblos, ever observant and innovative, soon followed suit, absorbing techniques and integrating them into their distinct cultural aesthetics.

The Genesis of Silver: From Trade to Craft

Early Pueblo silversmithing was often a quiet affair, with artisans initially acquiring silver through trade or by melting down coins. The first Pueblo silversmiths, particularly at Zuni and Hopi, likely learned directly from Navajo counterparts or through observation at trading posts, which became vital hubs for materials and market access. However, the Pueblos quickly developed their unique approaches, moving beyond the heavier, stamped silverwork common among the Navajo to focus on their profound connection to stone.

The Zuni Pueblo, in particular, became synonymous with the art of stone-setting. Their distinctive style, characterized by intricate inlay, petit point, and needlepoint techniques, transforms silver into a delicate frame for a mosaic of precisely cut stones. Zuni jewelers are masters of the channel inlay, where meticulously shaped pieces of turquoise, coral, jet, and mother-of-pearl are set side-by-side within silver channels, creating a smooth, uninterrupted surface. Their petit point and needlepoint work involves cutting tiny, often oval or tear-drop shaped stones and setting them in delicate silver bezels, forming elaborate patterns that can resemble lace or flowers. This exacting work demands extraordinary patience and a steady hand. "For us, the stone is alive," explains Leander Othole, a Zuni jeweler whose family has been crafting for generations. "Each piece of turquoise, each shell, has its own spirit. Our job is to bring that spirit forward, to let it shine in harmony with the silver." This reverence for materials is palpable in every finished piece, with common motifs including sunfaces, rain clouds, and animals, particularly the powerful Zuni fetish animals imbued with protective qualities.

A starkly different yet equally compelling style emerged from the Hopi mesas: the overlay technique. Developed primarily in the 1930s and 40s through a project initiated by the Museum of Northern Arizona, Hopi overlay is a sophisticated method involving two layers of silver. The top layer is meticulously cut with designs, often depicting Katsina figures, clan symbols, corn, rain clouds, or other elements deeply significant to Hopi cosmology and agrarian life. This cut-out layer is then soldered onto a solid bottom layer, which has been darkened (oxidized) and textured, creating a dramatic contrast that makes the intricate designs "pop." The result is a bold, graphic aesthetic that speaks volumes about Hopi cultural identity. Each symbol is laden with meaning, serving not just as decoration but as a visual prayer or narrative. The precision required to cut these intricate designs, often freehand, and the careful filing and polishing to achieve a seamless finish, demonstrate the profound skill of Hopi artisans.

The Kewa Pueblo, formerly known as Santo Domingo, holds a unique place in the history of Pueblo jewelry, primarily celebrated for its ancient tradition of heishi. This involves meticulously cutting, grinding, and polishing tiny beads from shell (clam, olivella, abalone), turquoise, and other stones, then stringing them into necklaces. While heishi pre-dates silverwork, Kewa jewelers seamlessly integrated silver into their craft, often creating simple, elegant silver bezels for larger turquoise stones or incorporating silver beads and spacers into their heishi strands. Their silverwork often leans towards a more classic, unembellished style, allowing the natural beauty of the stones and the inherent elegance of the silver to take center stage. Kewa mosaic inlay, where small, flat pieces of stone are adhered to a backing, sometimes with pitch, is another testament to their ancient connection to stone.

Cultural Significance: Beyond Adornment

For the Pueblo peoples, jewelry is never merely an accessory; it is an extension of identity, a connection to heritage, and a vessel for cultural narratives. Each design, each stone, each technique is imbued with meaning, carrying the weight of generations of spiritual understanding and communal history. Jewelry is worn in ceremonies, passed down as heirlooms, and serves as a visible affirmation of one’s place within the community and the cosmos. The act of creation itself is often a meditative and prayerful process, reflecting the deep respect artisans hold for their materials and their craft.

The symbols incorporated into Pueblo jewelry are not random; they are sacred. The Zuni sunface represents the sacred giver of life. Hopi Katsinas embody spirits that bring rain and blessings. The corn motif, ubiquitous across many Pueblos, symbolizes sustenance, life, and the central role of agriculture. Wearing these symbols is a way of carrying one’s culture, history, and spiritual beliefs outwardly, fostering a sense of pride and belonging.

Artistic Innovations: Honoring the Past, Forging the Future

While deeply rooted in tradition, Pueblo silversmithing is far from static. Contemporary Pueblo jewelers are vibrant innovators, pushing the boundaries of their craft while maintaining an unwavering respect for their cultural heritage. This new wave of artists integrates modern aesthetics, explores new materials, and combines techniques in exciting ways, ensuring the art form remains relevant and dynamic.

Artists like Jesse Monongye (Navajo/Hopi) or the work coming from the younger generation of Zuni and Hopi families exemplify this blend. They might incorporate abstract designs into traditional overlay, or utilize unusual cuts of turquoise and other semi-precious stones in their inlay work, moving beyond the conventional color palettes. Some experiment with different metals, textures, and even incorporate elements from other art forms, creating pieces that are both unmistakably Pueblo and strikingly contemporary.

"Innovation doesn’t mean abandoning tradition; it means understanding it so deeply that you can speak a new language with the same soul," states a curator at the Indian Arts Research Center in Santa Fe, observing the evolving landscape. "These artists are not just making beautiful objects; they’re continuing a conversation that began centuries ago, adding their own voices and perspectives."

This evolution is often driven by individual artistic vision, but also by market demands and exposure to global art trends. Pueblo jewelers now exhibit in prestigious galleries and museums worldwide, bringing their art to a broader audience and gaining recognition for their individual contributions. This exposure, however, comes with its own set of challenges, including concerns about cultural appropriation and the need to educate buyers about authenticity and the profound cultural context of the work.

Challenges and Preservation

Despite its vibrancy, Pueblo silversmithing faces contemporary challenges. The scarcity and rising cost of high-quality natural turquoise, the lifeblood of much Pueblo jewelry, poses a significant hurdle. Economic pressures can tempt some artisans to compromise on traditional techniques or materials. Moreover, the encroachment of mass-produced, often imported, "Native-style" jewelry threatens the economic viability of authentic handmade pieces.

However, determined efforts are underway to preserve and promote this vital art form. Tribal cultural centers, educational programs, and dedicated organizations work to mentor young artisans, ensuring that the intricate techniques and profound cultural knowledge are passed on. Many artists are also fiercely protective of their designs and cultural narratives, actively educating the public about the difference between genuine Pueblo art and imitations.

In conclusion, Pueblo silversmithing is a living, breathing art form—a magnificent tapestry woven from history, spirituality, and unparalleled artistic skill. From the ancient reverence for turquoise to the sophisticated silver techniques developed over generations, and the exciting innovations of today’s artists, Pueblo jewelry embodies a deep connection to land, culture, and identity. It is more than just jewelry; it is a profound expression of a people’s enduring spirit, a shimmering testament to their resilience, creativity, and the timeless beauty they continue to share with the world. Each piece tells a story, a silent yet eloquent echo of the traditions that shaped it and the innovations that ensure its future.