The Enduring Hearth: A Centuries-Long Struggle for Pueblo Land in New Mexico

In the high desert expanse of New Mexico, where ancient adobe villages cling to the earth and the Rio Grande carves its path through sun-baked mesas, the story of Pueblo land grants is not merely a legal history; it is the enduring narrative of a people, their culture, and their tenacious connection to the very ground beneath their feet. For centuries, the Pueblo people have navigated shifting colonial powers – Spanish, Mexican, and American – each bringing their own legal frameworks, yet consistently confronting the Pueblos’ deep-seated, communal understanding of land as a living, sacred entity, not just a commodity. This clash of worldviews has forged a complex and often painful struggle for land rights, sovereignty, and cultural survival that continues to resonate today.

The roots of this saga stretch back millennia, long before European arrival. The Pueblo people, descendants of the ancestral Puebloans, had established sophisticated agricultural societies across the Southwest, their lives inextricably linked to the land and its life-giving waters. Their villages, or pueblos, were not just dwellings but spiritual centers, economic hubs, and the heart of their communal identity. When the Spanish arrived in the late 16th century, they brought with them a system of land ownership entirely alien to the Pueblos, but one that, paradoxically, offered a degree of protection.

Under Spanish colonial law, a system of land grants was established, designed to both reward colonists and protect Indigenous communities. The Pueblos, unlike many other Native American groups, were recognized as distinct political entities. Royal decrees, such as the Recopilación de Leyes de los Reinos de Indias (Compilation of the Laws of the Kingdoms of the Indies), mandated that each Pueblo be granted a communal land base, typically a "four league square" (approximately 17,000 acres) surrounding their village. These grants, though imposed, formally recognized the Pueblos’ occupancy and provided a legal basis for their continued existence. As historian Myra Ellen Jenkins noted, "The Spanish Crown, for all its colonial ambitions, recognized the Pueblos as settled, agricultural communities and sought to incorporate them, however uneasily, into its broader social and legal framework." These grants were held communally, for the benefit of the entire Pueblo, and could not be alienated or sold by individual members.

The Mexican period, following independence from Spain in 1821, largely maintained the existing land grant system. While some changes in administration occurred, the principle of communal Pueblo ownership was generally respected. However, this fragile stability was shattered with the conclusion of the Mexican-American War in 1848 and the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. This treaty, which ceded vast territories including New Mexico to the United States, promised to respect the property rights of Mexican citizens, a category that technically included the Pueblo people. But the transition to American rule ushered in an era of unprecedented legal complexity, fraud, and dispossession for the Pueblos.

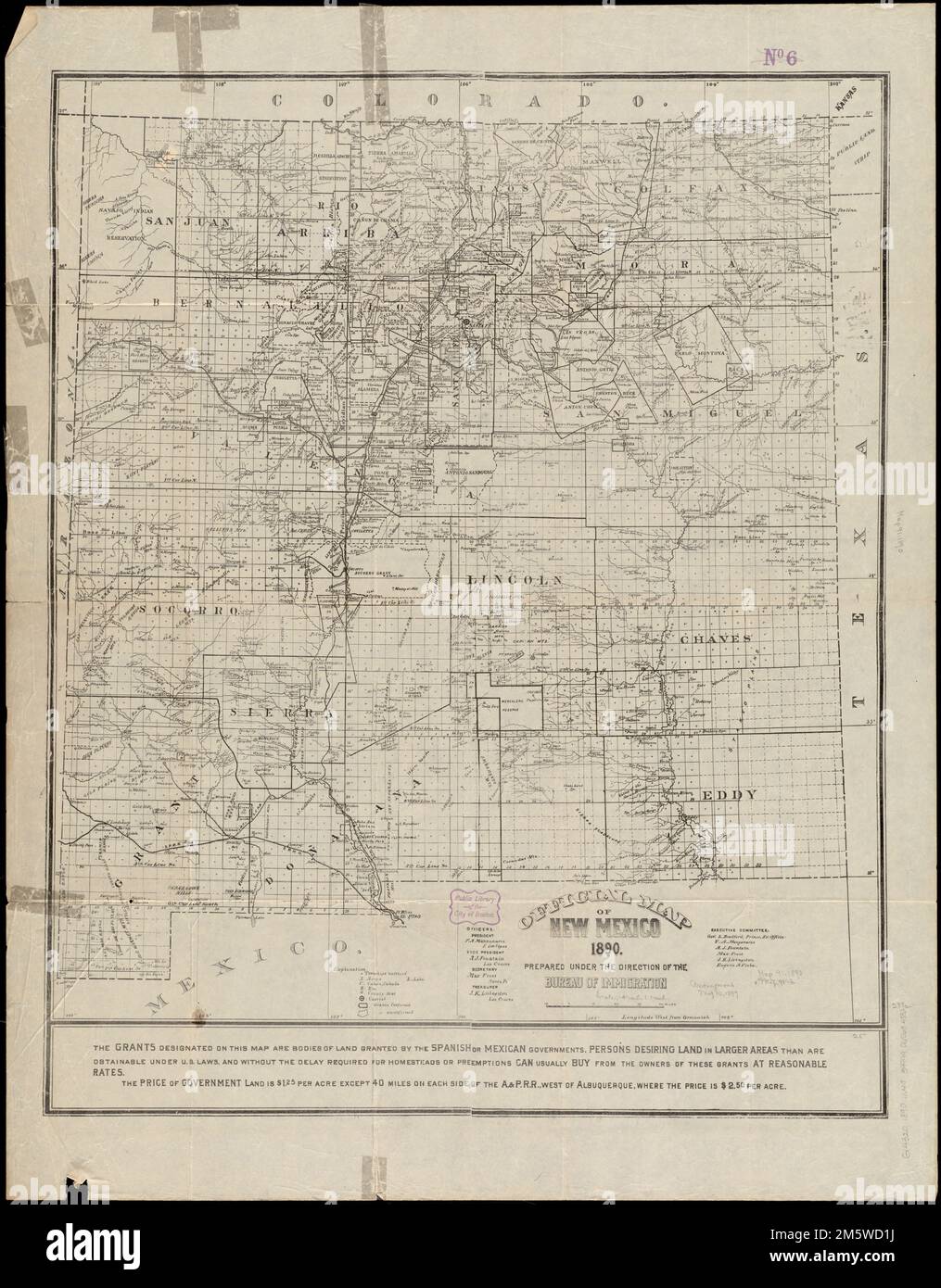

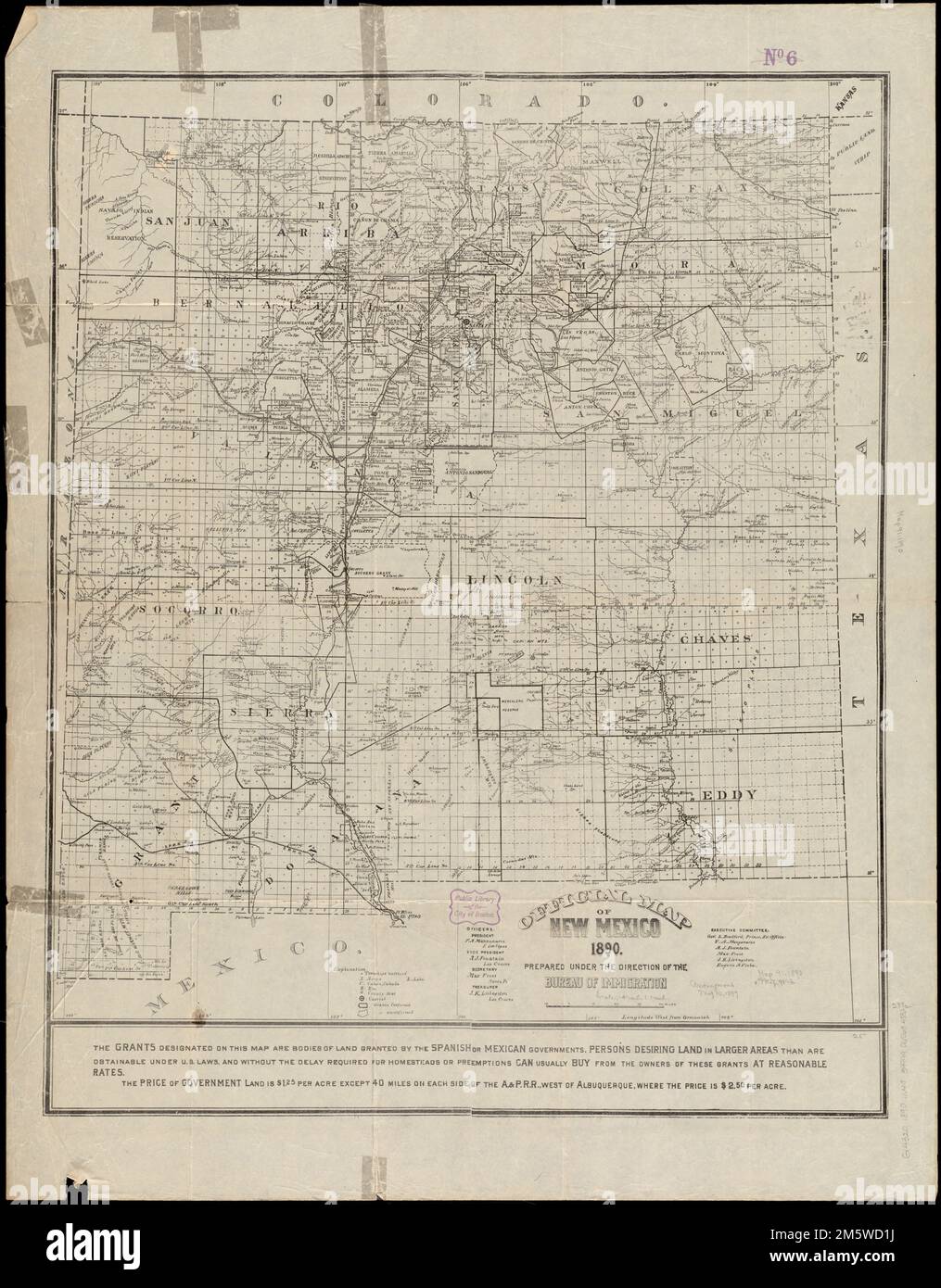

The American legal system, rooted in English common law, emphasized individual private property ownership, a stark contrast to the communal traditions of the Pueblos and the Spanish/Mexican grant system. The U.S. government faced the monumental task of validating thousands of land claims in New Mexico, many of which were poorly documented or based on oral tradition. Congress established the Office of the Surveyor General in 1854 to investigate these claims. However, this office was often underfunded, understaffed, and lacked a full understanding of the intricate Spanish and Mexican legal traditions.

The consequences for the Pueblos were dire. Their communal grants, clearly defined under Spanish law, were often challenged or encroached upon by Anglo settlers, Mexican vecinos (neighbors), and land speculators. The burden of proof fell heavily on the Pueblos, who were often illiterate in English, lacked financial resources, and faced a legal system entirely foreign to them. Many Pueblos found themselves locked in protracted legal battles, trying to defend lands they had occupied for centuries against claimants armed with dubious documents or simply the raw power of Manifest Destiny.

"The American acquisition was a legal quagmire for the Pueblos," explains legal scholar G. Emlen Hall in his work on New Mexico land grants. "The system was designed to resolve claims, but it often functioned to dispossess those who couldn’t navigate its labyrinthine processes or defend against opportunistic claims."

The situation worsened with the creation of the Court of Private Land Claims in 1891, specifically tasked with resolving the remaining land grant claims in the Southwest. While intended to bring finality, this court was often hostile to claims not supported by perfect documentation and rejected a significant number of legitimate grants. For the Pueblos, this meant further losses. Their ancient communal holdings, once protected by Spanish law, were increasingly vulnerable. Squatters moved onto their lands, diverted their crucial irrigation waters, and disrupted their traditional agricultural practices.

A critical turning point, and one of the most significant legal battles for the Pueblos, centered on the issue of their legal status. In 1913, the U.S. Supreme Court, in United States v. Sandoval, ruled that the Pueblo Indians were indeed "wards of the government," similar to other federally recognized tribes. While this ruling aimed to protect them from further exploitation, it also stripped them of their full citizenship rights and opened the door for the federal government to intervene in their land affairs. More importantly, it clarified that the Pueblos had a unique status: their lands were not merely private property but communal holdings deserving of federal protection, distinct from other private land claims.

This clarification, however, came after decades of encroachment. By the early 20th century, thousands of non-Pueblo individuals had settled on Pueblo lands, often in good faith, having purchased parcels from individual Pueblo members who did not have the right to sell communal property. This created an impossible situation, pitting the Pueblos’ ancient rights against the perceived property rights of the settlers.

The crisis culminated in the 1920s with the Bursum Bill, a proposed piece of legislation that would have effectively validated many non-Pueblo claims to Pueblo lands, legitimizing the theft. The Pueblos, recognizing the existential threat, united in an unprecedented act of pan-Pueblo resistance. The All Pueblo Council (now the Council of All Pueblo Governors), a body with roots stretching back to the 17th century Pueblo Revolt, galvanized opposition. They sent delegations to Washington D.C., lobbied Congress, and garnered support from sympathetic lawyers, anthropologists, and women’s groups.

Their impassioned advocacy led to the defeat of the Bursum Bill and, crucially, the passage of the Pueblo Lands Act of 1924. This landmark legislation created a Pueblo Lands Board to investigate all non-Indian claims to Pueblo land. While it affirmed Pueblo title to some lands, it also established a system of compensation for Pueblos whose lands had been lost to valid non-Indian claims and, conversely, compensated non-Indians who had legitimately purchased land that was ultimately deemed Pueblo. While imperfect and resulting in significant land losses, the Act provided a legal framework for resolving decades of disputes and, most importantly, affirmed the communal nature of Pueblo land ownership under U.S. law.

Yet, the struggle did not end there. Perhaps the most celebrated victory for Pueblo land rights came nearly half a century later with the return of Blue Lake to Taos Pueblo in 1970. Blue Lake, a high-altitude alpine lake and the surrounding wilderness, is the most sacred site for Taos Pueblo, integral to their spiritual ceremonies and cultural identity. Despite its profound significance, the U.S. government had seized the land in 1906, incorporating it into the Carson National Forest. For decades, Taos Pueblo fought tirelessly for its return, arguing that without access to Blue Lake, their very spiritual existence was threatened.

"Blue Lake is our church, our university, our life," stated a Taos Pueblo elder during the campaign for its return. "It is the source of our strength and the essence of our being."

After years of lobbying, congressional hearings, and persistent advocacy, President Richard Nixon signed legislation returning Blue Lake and 48,000 acres of surrounding wilderness to Taos Pueblo. This historic act marked a profound recognition of Indigenous religious freedom and land rights, setting a precedent for future land returns to Native American nations.

Today, the Pueblo people continue to grapple with the legacy of land grants. While their core communal lands are largely secure, issues of water rights, resource management, economic development, and cultural preservation remain central. Many Pueblos still pursue claims for ancestral lands lost outside their recognized grants, viewing these lands not as mere property but as extensions of their spiritual and cultural domain. The ongoing challenges include protecting their unique water rights in an arid region, managing their natural resources sustainably, and balancing traditional practices with the demands of a modern economy.

The Pueblo land grants of New Mexico are more than just historical footnotes; they are living documents, testaments to the resilience of a people who have faced immense pressure to assimilate and relinquish their heritage. Their story is a powerful reminder that land is often far more than just real estate; it is identity, spirituality, economy, and the very foundation of a culture. The enduring hearths of the Pueblo villages, still burning after centuries of struggle, stand as a testament to an unwavering connection to the land, a connection that continues to define their past, shape their present, and illuminate their future.