The Paradox of Piety: Unearthing New England’s Praying Towns

In the annals of American colonial history, the Puritan settlements of New England often evoke images of stern-faced settlers, unyielding religious fervor, and the relentless march of European civilization across a vast wilderness. Yet, nestled within this narrative lies a complex and often tragic chapter: the rise and fall of the "Praying Towns." These were not mere outposts of missionary zeal but meticulously planned communities where Native Americans, under the tutelage of Puritan ministers, were encouraged to abandon their ancestral ways, embrace Christianity, and adopt English customs. Conceived as a grand experiment in salvation and "civilization," the Praying Towns ultimately became a crucible where ideals clashed with harsh realities, leaving behind a legacy of both earnest endeavor and profound cultural loss.

The story of the Praying Towns begins in the mid-17th century, a period marked by increasing English settlement and the growing theological conviction among Puritans that they had a divine mandate to convert the indigenous peoples. For many, the unchurched Native Americans represented souls lost to "savagery" and ripe for redemption. This fervent belief was epitomized by figures like John Eliot, a brilliant and indefatigable minister from Roxbury, Massachusetts. Eliot, often dubbed the "Apostle to the Indians," embarked on an extraordinary mission that would consume decades of his life. He recognized that true conversion required more than sermons; it demanded a deep understanding of the Native language and culture.

Eliot immersed himself in the Massachusett language, learning its intricate grammar and vocabulary with remarkable dedication. He even published a primer in 1654 and, in a monumental achievement, completed the first complete Bible printed in America in 1663 – a translation entirely in the Massachusett tongue. This "Mamusse Wunneetupanatamwe Up-Biblum God" was a testament to his linguistic prowess and unwavering commitment. Eliot believed that by bringing the Word of God directly to the Native peoples in their own language, he could transform them into pious, self-governing Christian communities.

The first Praying Town, Natick, was established in 1651 on the Charles River. It was envisioned as a utopian experiment, a model for future settlements. Here, Native converts, primarily from the Massachusett, Nipmuc, and Wampanoag tribes, were encouraged to adopt English-style housing, farming techniques, and dress. They were taught to read and write, with the Bible as their primary text. The towns were governed by a strict moral code derived from Puritan law, enforced by Native magistrates chosen from among the converts. Traditional practices like polygamy, powwows (spiritual gatherings), and the "greasing of their hair" were forbidden. Sabbath observance was mandatory, and disputes were settled in English-style courts. The aim was not just spiritual conversion but a wholesale cultural transformation, turning "wild men" into "civilized" English subjects.

For the Native Americans, the decision to join a Praying Town was rarely simple or monolithic. For some, there was genuine spiritual curiosity and a desire to embrace the new faith, perhaps seeing parallels or finding solace in its teachings during a time of immense societal upheaval. Others may have sought the practical benefits offered by the English: protection from rival tribes, access to European tools and goods, or a means to navigate the increasingly complex political landscape dominated by the colonists. For a people whose traditional lands were rapidly being encroached upon, aligning with the powerful English might have seemed a pragmatic choice for survival. Yet, this came at a significant cost: the erosion of their ancestral identity, customs, and self-determination. They were, in essence, asked to become "brown Englishmen," as one historian noted.

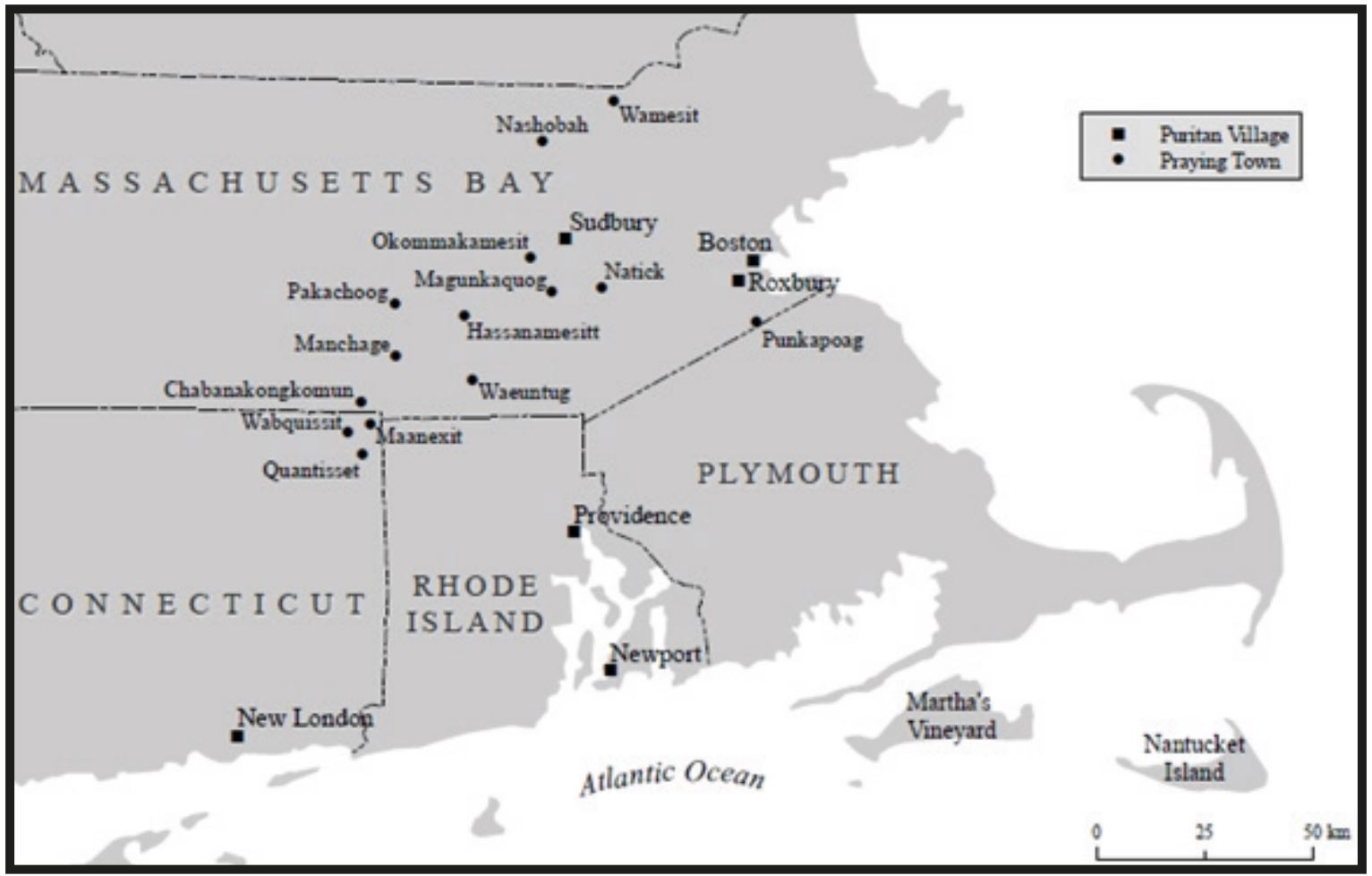

By the early 1670s, there were fourteen established Praying Towns in Massachusetts, with others in Plymouth Colony, housing an estimated 2,500 Native converts. These communities, seemingly flourishing under Puritan guidance, represented a unique frontier where two vastly different cultures intersected, albeit with a profound power imbalance. They were seen by the Puritans as shining examples of their missionary success, a validation of their divine purpose in the New World.

However, this fragile experiment was destined to be shattered by the outbreak of King Philip’s War in 1675. This brutal and devastating conflict, led by Metacom (known to the English as King Philip), the sachem of the Wampanoag, pitted Native tribes against the English colonists in a desperate struggle for land and sovereignty. The war proved to be the ultimate test for the Praying Indians, who found themselves caught in an impossible bind.

To the English colonists, many of whom harbored deep-seated prejudices and fears, the Praying Indians became objects of intense suspicion. Despite their outward adherence to English ways and their Christian faith, they were still "Indians." Rumors of their disloyalty, often unfounded, spread like wildfire. Colonists feared that the Praying Towns were merely Trojan horses, providing refuge or intelligence to Metacom’s forces. This paranoia led to horrific acts of injustice.

In a dark chapter of colonial history, the Massachusetts General Court ordered the internment of most Praying Indians. Hundreds were forcibly removed from their homes and banished to barren, windswept islands in Boston Harbor, most notably Deer Island. Here, without adequate shelter, food, or medical supplies, they endured a brutal winter. Many starved, froze, or succumbed to disease. One observer noted the "great suffering" of these "poor, naked, starved creatures." This act of collective punishment stands as a stark betrayal of the promise of protection and salvation that had drawn many Natives to the towns.

Yet, even amidst this persecution, some Praying Indians continued to demonstrate their loyalty to the English, often acting as invaluable scouts, guides, and interpreters. Their knowledge of the terrain and Native languages proved crucial for the colonial forces, often turning the tide in crucial engagements. Ironically, these "praying Indians" were simultaneously reviled by their non-Christian kin for collaborating with the enemy and distrusted by the English for their ethnicity. They existed in a perilous limbo, "between two fires," as one historian described it.

The end of King Philip’s War in 1676, with Metacom’s defeat and death, brought a fragile peace but irrevocably altered the landscape of New England. For the Praying Towns, the war was a death knell. The surviving inhabitants, decimated by disease and violence, returned to find their homes destroyed, their lands encroached upon, and their communities shattered. The deep-seated mistrust that had taken root during the conflict proved impossible to overcome.

In the decades that followed, the remaining Praying Towns dwindled. Their lands were gradually absorbed by expanding English settlements, and their distinct identity eroded under the weight of colonial pressure and persistent discrimination. While some communities, like Natick and Mashpee, managed to persist, they did so in a vastly diminished state, often struggling to maintain their cultural integrity and land rights against overwhelming odds.

The legacy of the Praying Towns is a complex tapestry woven with threads of genuine missionary zeal, cultural assimilation, survival strategies, and profound injustice. They represent a unique and often uncomfortable lens through which to view the early encounters between European colonists and Native Americans. They were a testament to the Puritan belief in their divine mission, but also a stark reminder of the devastating consequences of imposing one culture’s worldview upon another, particularly when power is so unequally distributed.

Today, the sites of these former Praying Towns stand as silent witnesses to a pivotal era. Descendants of the Praying Indians, such as the Nipmuc and Massachusett, continue to preserve their heritage, reclaiming the narratives that were once suppressed. The story of the Praying Towns reminds us that history is rarely simple, often containing layers of intention and outcome, hope and despair, all contributing to the intricate and enduring human story of colonial New England. It is a story of faith, survival, and the enduring paradox of piety in a land claimed by conquest.