From Sovereignty to Silence and Resurgence: The Enduring Legacy of the Pequot Tribe

Beyond the glittering facades of Foxwoods Resort Casino, nestled amidst the rolling hills and dense forests of southeastern Connecticut, lies a story far richer, deeper, and more complex than modern commercial success. It is the narrative of the Pequot Tribe, a people whose history is a powerful testament to pre-colonial sovereignty, devastating conflict, forced erasure, and an extraordinary resurgence against overwhelming odds. The Pequot story is not merely a regional curiosity; it is a microcosm of the Indigenous experience in North America, embodying the profound impacts of colonialism and the enduring spirit of a people determined to reclaim their identity and future.

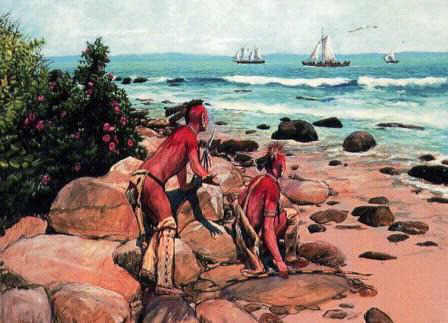

For centuries before European contact, the Pequot, an Algonquian-speaking people, were a dominant force in what is now southeastern Connecticut. Their name, often translated as "destroyers" or "foxes," spoke to their prowess and influence. Their ancestral lands stretched along the coast from the Niantic River to the Pawcatuck River, extending inland to the present-day towns of Preston and Norwich. This strategic location, encompassing fertile river valleys and abundant coastal waters, allowed them to flourish.

Pequot society was sophisticated and well-organized. They were master horticulturists, cultivating vast fields of corn, beans, and squash, which formed the bedrock of their diet. Their hunting parties pursued deer, bear, and smaller game, while their expert fishermen harvested cod, shellfish, and migratory fish from the Atlantic and its tributaries. Their impressive dugout canoes, carved from single tree trunks, enabled them to navigate coastal waters and rivers, facilitating extensive trade networks.

Crucially, the Pequot were central to the production and trade of wampum, shell beads meticulously crafted from quahog and whelk shells. Wampum was far more than mere currency; it was a sacred item, used in ceremonies, as diplomatic gifts, and as a record-keeping device. Its creation and control bestowed immense political and economic power, placing the Pequot at the nexus of inter-tribal relations and solidifying their status as a regional powerbroker. Their sachems, or leaders, governed with a blend of authority and consensus, maintaining a complex web of alliances and occasional conflicts with neighboring tribes like the Narragansett, Mohegan, and Niantic.

The arrival of Europeans in the early 17th century irrevocably altered this established order. Initially, the Dutch and English sought trade, primarily for furs, which the Pequot were well-positioned to supply. However, this interaction also brought unforeseen and catastrophic consequences. European diseases, against which Native Americans had no immunity, swept through communities with devastating speed. Smallpox, measles, and other pathogens decimated populations, weakening tribes and disrupting social structures.

As European settlements expanded, particularly those of the English Puritans from Massachusetts Bay and Plymouth, competition for land and resources intensified. The English, driven by a desire for expansion and a belief in their divine right to the land, viewed the Pequot as an obstacle to their colonial ambitions. Cultural misunderstandings compounded the growing friction. The English concept of land ownership—individual, permanent, and exclusive—clashed fundamentally with the Indigenous understanding of land use—communal, seasonal, and shared.

Tensions escalated throughout the 1630s. Disputes over trade, accusations of murder (including the deaths of English traders John Stone and John Oldham, though the specifics of Pequot involvement remain debated), and the English desire to break Pequot dominance fueled a climate of paranoia and aggression. The Pequot, under the leadership of their principal sachem, Sassacus, found themselves increasingly isolated as the English skillfully manipulated inter-tribal rivalries, particularly with the Narragansett and a faction of the Mohegan led by Uncas, who had recently broken from the Pequot.

This volatile situation erupted into the Pequot War in 1637, a conflict that would forever scar the Pequot people and reshape the geopolitical landscape of New England. The English, allied with the Mohegan and Narragansett, launched a series of punitive expeditions. The decisive and most brutal event of the war occurred on May 26, 1637, when a combined force of English colonists and their Native allies attacked the fortified Pequot village at Mystic.

The attack was swift and merciless. Under the command of Captain John Mason, English soldiers surrounded the palisaded village before setting it ablaze. As the Pequot tried to escape the inferno, they were cut down by musket fire. "Those that scaped the fire," Mason wrote, "were slain with the sword; some hewed to pieces, others run through with their rapiers, so as they were quickly dispatched and very few escaped." William Bradford, a leader of Plymouth Colony, later recorded the horrific scene: "It was a fearful sight to see them thus frying in the fire and the streams of blood quenching the same, and horrible was the stink and scent thereof; but the victory seemed a sweet sacrifice, and they gave praise thereof to God, who had wrought so wonderfully for them." Estimates suggest that between 400 and 700 Pequot men, women, and children were killed in less than an hour, effectively annihilating a significant portion of the tribe.

The Mystic Massacre was a strategic act of terror, intended to break the Pequot’s will to resist and serve as a brutal warning to other Indigenous nations. Following the massacre, the remaining Pequot were relentlessly hunted. Sassacus and his followers attempted to flee west but were ultimately betrayed and killed by the Mohawk.

The war concluded with the Treaty of Hartford in 1638, a document designed not for peace, but for the complete dissolution of the Pequot as a political entity. The treaty explicitly forbade the use of the name "Pequot," scattering the surviving members among the Narragansett, Mohegan, and Niantic as servants or slaves. Many were shipped to the West Indies as slaves. It was a deliberate attempt at cultural and political annihilation, a decree of non-existence. The English declared the Pequot extinct.

Yet, despite the immense trauma and the official declaration of their demise, the Pequot persisted. Small groups, refusing to abandon their identity, began to coalesce in isolated pockets of their ancestral lands. Over generations, two distinct communities emerged: the Mashantucket Pequot, who gathered near the present-day town of Ledyard, and the Eastern Pequot, who established themselves in North Stonington. Their existence was often precarious, marked by poverty, discrimination, and constant pressure from surrounding colonial settlements. They maintained their cultural traditions in secret, passing down stories, language fragments, and ceremonies through oral tradition, a defiant act against erasure.

For centuries, these communities struggled for recognition and self-determination. They fought land disputes, petitioned colonial and later state governments, and maintained their communal identities despite overwhelming odds. Their history became one of quiet resilience, of refusing to disappear even when their very name was legally proscribed.

The late 20th century, however, marked a dramatic turning point. A new generation of Pequot leaders, armed with meticulous historical research and a fierce determination, began the arduous process of seeking federal recognition from the United States government. This was a critical step towards reclaiming their sovereignty and securing rights and benefits afforded to federally recognized tribes.

In 1983, after a long and exhaustive process, the Mashantucket Pequot Tribe achieved federal recognition. This landmark decision affirmed their continuous existence as a distinct tribal nation, overturning the centuries-old declaration of their extinction. With federal recognition came the right to self-governance and the ability to pursue economic development on their sovereign land.

What followed was nothing short of a modern economic and cultural renaissance. In 1992, the Mashantucket Pequot opened Foxwoods Resort Casino, which rapidly grew into one of the largest and most successful casino operations in the world. The revenues generated from Foxwoods transformed the tribe’s fortunes, allowing them to reinvest in their community, provide housing, healthcare, education, and cultural programs for their members. They established the Mashantucket Pequot Museum & Research Center, a world-class institution dedicated to preserving and sharing the history and culture of the Pequot and other Native peoples of the Northeast. This museum stands as a powerful symbol of their resurgence, turning a history of silence into a vibrant, educational voice.

The Eastern Pequot Tribe also pursued federal recognition, facing a more protracted and complex journey due to historical factors and political opposition. After years of legal battles, they too were granted federal recognition in 2002, though this was later challenged and reversed, leaving their status in a more ambiguous state and highlighting the ongoing complexities of tribal recognition.

The Pequot story, therefore, is not a static historical account but a living, evolving narrative. It encompasses the pre-colonial strength of a thriving people, the devastating impact of the Pequot War and the subsequent attempt at annihilation, and the incredible fortitude shown in maintaining identity through centuries of adversity. Their modern resurgence, spearheaded by the Mashantucket Pequot, demonstrates the power of self-determination and economic sovereignty to rebuild and thrive.

The Pequot legacy serves as a vital reminder that history is often told by the victors, but the truth of a people’s experience endures. From the ashes of Mystic, through generations of struggle, the Pequot have not only survived but have reclaimed their voice, their land, and their rightful place as a sovereign nation. Their story challenges us to look beyond simplistic narratives and to recognize the profound resilience and enduring spirit of Indigenous peoples in the face of immense historical trauma. The Pequot are not just a part of Connecticut’s past; they are a vibrant and essential part of its present and future.