Echoes of Eternity: Pacific Northwest Indigenous Sustainability Practices Reshape the Future

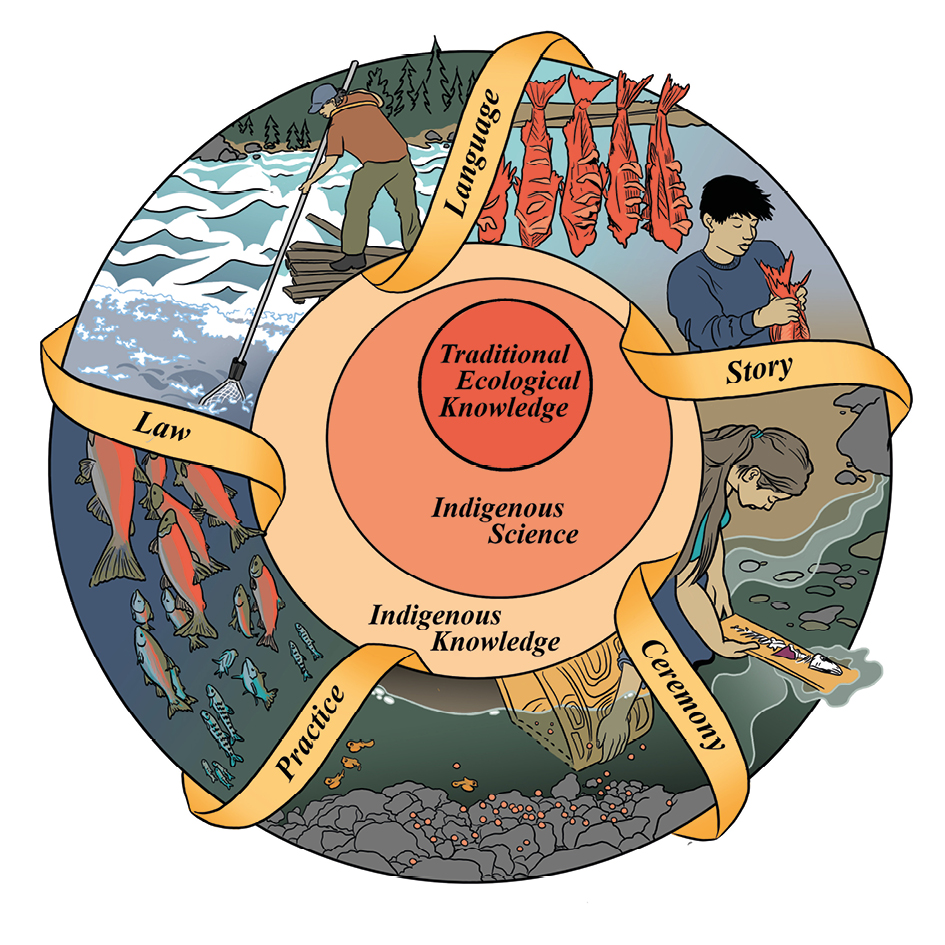

In the verdant, rain-soaked landscapes of the Pacific Northwest, a profound testament to enduring human ingenuity and ecological harmony has thrived for millennia. Long before the arrival of European settlers, Indigenous peoples of this region cultivated a sophisticated and sustainable relationship with their environment, not merely surviving but flourishing through practices rooted in deep respect, reciprocity, and an unparalleled understanding of their ecosystems. These Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) systems, passed down through countless generations, offer critical lessons for a world grappling with climate change, biodiversity loss, and resource depletion. Far from being relics of the past, these practices are being revitalized today, offering a beacon for a more sustainable future.

The Pacific Northwest, stretching from the temperate rainforests of British Columbia down to northern California, is home to hundreds of distinct Indigenous nations, each with unique languages, cultures, and traditions. Yet, a unifying thread through their diverse societies has always been a holistic approach to land and resource management. This worldview fundamentally differs from Western paradigms of resource extraction; it sees humans not as separate from nature, but as an integral part of an interconnected web of life, responsible for its stewardship.

The Foundation of Reciprocity: Living with the Land, Not Just On It

At the heart of Indigenous sustainability is the principle of reciprocity – the understanding that if the land and its creatures provide for you, you must, in turn, care for them. This isn’t just a spiritual belief; it’s a practical guide for resource management. Knowledge of local flora and fauna, seasonal cycles, weather patterns, and ecological relationships was meticulously observed, tested, and transmitted through oral traditions, stories, ceremonies, and hands-on learning. This deep knowledge allowed for selective harvesting, resource enhancement, and proactive management strategies that ensured abundance for future generations. The concept of "seven generations" – making decisions with the impact on the seventh generation in mind – encapsulates this profound long-term perspective.

"We manage the landscape, we don’t just live on it," states Dr. Kim Recalma-Clutesi (Kwalilas), a Kwakwaka’wakw Hereditary Chief and expert in traditional clam gardens. This statement succinctly captures the proactive, stewardship-oriented approach that characterized Indigenous land management. This wasn’t a pristine wilderness untouched by human hands; it was a carefully cultivated garden on an epic scale.

Salmon: The Lifeblood and a Masterclass in Management

Perhaps no single resource epitomizes the intricate sustainability practices of the PNW more than salmon. For countless nations like the Coast Salish, Haida, Tlingit, Kwakwaka’wakw, and Nez Perce, salmon are not just food; they are "our relatives," central to culture, economy, and spirituality. The sophisticated management of salmon runs, which sustained populations for thousands of years, stands in stark contrast to the dramatic declines seen since industrial fishing and damming.

Indigenous communities developed elaborate systems for salmon management. Fish weirs and traps, often made of intricate wooden structures, were designed not to deplete stocks but to allow sufficient numbers of salmon to pass upstream to spawn. These systems enabled selective harvesting – allowing smaller, less robust fish to pass while taking larger, older ones, thereby enhancing genetic diversity and overall stock health. Furthermore, stream maintenance, including clearing logjams and enhancing spawning grounds, was a regular practice. The knowledge of distinct salmon runs, their timing, and their specific needs allowed for precision harvesting that ensured sustainability.

"Salmon are not just food; they are our teachers, our spiritual guides, and the heart of our culture," is a sentiment echoed across many Indigenous communities. This deep connection fostered practices that prioritized the health of the salmon over short-term gains, recognizing that the health of the people was inextricably linked to the health of the salmon.

Cultivating the Wild: Forests, Prairies, and the Intertidal Zone

Beyond salmon, Indigenous communities actively managed nearly every aspect of their environment:

-

Forest Management and Cultural Burning: The old-growth forests of the PNW were not simply "wild" but managed ecosystems. Controlled, low-intensity burns – known as cultural burning – were regularly employed. These "cool burns" cleared underbrush, reduced fuel loads (preventing catastrophic wildfires), enhanced habitat for game, promoted the growth of culturally important plants like berries and camas, and fertilized the soil. This practice, largely suppressed by colonial fire management policies, is now being recognized as a vital tool in mitigating modern wildfire crises. The Quinault Nation, for instance, is actively working to reintroduce traditional burning practices on their ancestral lands.

-

Camas and Root Gardens: In open prairie and meadow areas, particularly in the interior and southern PNW, Indigenous peoples cultivated camas (Camassia quamash) – a vital starchy food staple. They used tools to turn the soil, remove competing plants, and manage water, essentially creating vast "root gardens." This cultivation not only ensured a reliable food source but also enriched the soil and maintained biodiversity.

-

Clam Gardens and Shellfish Aquaculture: Along the coast, Indigenous communities engineered the intertidal zone to enhance shellfish production. "Clam gardens" are ancient rock walls built at the low tide line, which flatten the beach slope, trap sediments, and create ideal habitat for clams. Research has shown that these managed beaches can increase clam biomass by 200-400% compared to unmanaged areas. This sophisticated form of aquaculture demonstrates an advanced understanding of marine ecology and geomorphology, ensuring a consistent and abundant food supply for millennia. The Kwakwaka’wakw, Snuneymuxw, and other coastal nations are actively revitalizing these practices.

-

Cedar Stewardship: The Western Red Cedar (Thuja plicata) is often called the "Tree of Life" by many PNW nations, providing everything from shelter and canoes to clothing and ceremonial items. Harvesting cedar was done sustainably, often by taking bark strips without felling the tree, allowing it to continue growing and providing for future generations. Trees were carefully selected, and harvesting was done respectfully, often with offerings and prayers.

The Impact of Disruption and the Path to Revitalization

The arrival of European settlers fundamentally disrupted these intricate and sustainable systems. Colonial policies, driven by resource extraction, land ownership, and cultural assimilation, led to the suppression of traditional practices, forced relocation, the imposition of industrial logging and fishing, and the damming of rivers. The introduction of foreign diseases and the violence of colonization decimated Indigenous populations, further eroding the transmission of TEK. The consequences are evident today in depleted salmon runs, degraded forests, and the loss of biodiversity.

However, the spirit of Indigenous sustainability was never extinguished. Today, there is a powerful movement of revitalization, with Indigenous communities leading efforts to restore their ancestral lands and practices. This resurgence is not just about cultural reclamation; it’s about applying millennia-old wisdom to contemporary environmental challenges.

- Co-management Agreements: Indigenous nations are increasingly entering into co-management agreements with federal and provincial governments, bringing their TEK to bear on modern resource management. Examples include collaborative efforts in fisheries management, forest fire prevention, and protected area designation.

- Restoration Projects: Communities are leading ambitious restoration projects, such as the removal of the Elwha Dam on the Olympic Peninsula, which allowed salmon to return to their ancestral spawning grounds for the first time in a century. Other projects focus on restoring clam gardens, replanting traditional food forests, and rehabilitating wetlands.

- Cultural Burning Revitalization: Tribes like the Karuk in California (southern PNW) and others in British Columbia are actively working with state and federal agencies to reintroduce cultural burning, demonstrating its effectiveness in reducing wildfire risk and restoring ecosystem health.

- Knowledge Sharing: Indigenous scholars and elders are working to document and share TEK, bridging the gap between traditional wisdom and Western science, showing how both can inform better environmental practices. Youth programs are vital in ensuring this knowledge continues to be passed down.

Lessons for a Global Future

The lessons emanating from the Pacific Northwest’s Indigenous communities are not relics of the past; they are urgent blueprints for the future. Their practices demonstrate that humans can live abundantly and sustainably within complex ecosystems without depleting them. They highlight the importance of:

- Holistic thinking: Recognizing the interconnectedness of all life.

- Long-term perspective: Prioritizing future generations over immediate gain.

- Adaptive management: Continuously observing, learning, and adjusting practices.

- Reciprocity and respect: Fostering a relationship of care with the natural world.

- Community-based stewardship: Empowering local communities with the knowledge and responsibility for their environment.

As the world grapples with unprecedented environmental crises, the wisdom embedded in Pacific Northwest Indigenous sustainability practices offers not just hope, but a proven path forward. By listening to and supporting Indigenous leadership, we can begin to mend our fractured relationship with the Earth and build a more resilient, equitable, and sustainable future for all. The echoes of eternity, carried in the songs of the salmon, the whisper of the cedar, and the turning of the tide in a clam garden, call us to remember and reclaim our role as stewards of this precious planet.