The Enduring Voices of the Pacific Northwest: A Tapestry of Language and Tradition

The Pacific Northwest coast, a land of ancient forests, mist-shrouded islands, and salmon-rich rivers, is not merely a geographic marvel; it is a cradle of profound human history, woven with an extraordinary diversity of indigenous languages and traditions. For millennia, the First Peoples of this vibrant region – stretching from present-day British Columbia down through Washington and Oregon – developed complex societies deeply attuned to their environment, their cultures articulated through a linguistic tapestry as rich and varied as the landscape itself. These languages are not mere communication tools; they are living repositories of knowledge, philosophy, and an enduring connection to the land and sea that shaped every facet of their existence.

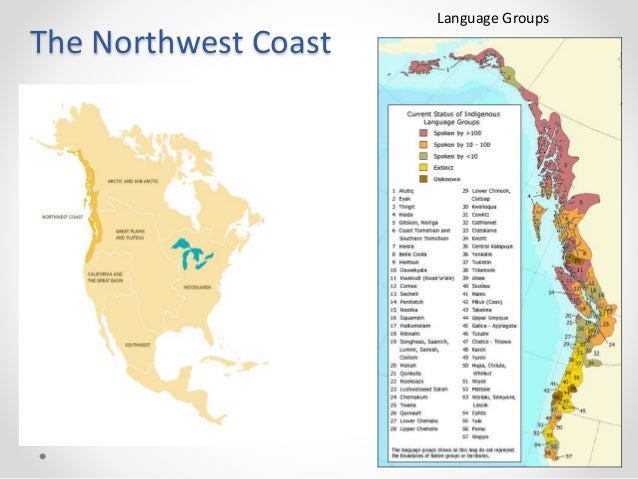

Before European contact, estimates suggest over 50 distinct languages, many with numerous dialects, thrived along this coast. This linguistic density is exceptional, reflecting centuries of independent development, adaptation, and interaction. These languages are broadly categorized into several major families, each with unique phonetic, grammatical, and conceptual structures that offer unparalleled insights into the worldview of their speakers.

The Linguistic Tapestry: Echoes of the Land

Among the most prominent language families is Salishan, a vast group spanning both coastal and interior regions. Along the coast, languages like Halkomelem, Squamish, Lushootseed (spoken by various Coast Salish peoples), and Comox-Sliammon flourished. Salishan languages are renowned for their complex phonology, often featuring sounds not found in European languages, and for their polysynthetic nature, where entire phrases or sentences can be expressed in a single verb-like word. A fascinating feature found in many Salishan languages is evidentiality, where speakers must indicate how they know the information they are conveying – whether they saw it, heard it, inferred it, or learned it through hearsay. This grammatical necessity subtly shapes perception and the very nature of truth-telling.

Further north, particularly on Vancouver Island and the central British Columbia coast, the Wakashan language family predominates. This includes languages such as Kwak’wala (spoken by the Kwakwaka’wakw), Nuu-chah-nulth (Nootka), and Haisla. Wakashan languages are known for their intricate morphology, often incorporating suffixes that specify location, manner, or instrument directly into verb stems. For instance, a single verb might convey "to cut something with an axe on the beach." The Nuu-chah-nulth phrase ʔiisaak-šiʔap-ḥi translates roughly to "look out for the future," encapsulating a philosophy of foresight and responsibility deeply embedded in their language.

Another unique family is Chimakuan, with Quileute being its sole surviving member, spoken by the Quileute Nation in Washington State. Its relative, Chimakum, is now extinct. Quileute is an isolate, meaning it has no known living relatives, highlighting the immense linguistic diversity that once characterized the region. Further north, the Haida language, spoken on Haida Gwaii (Queen Charlotte Islands), is also considered a language isolate, a linguistic island unto itself with its own distinct sounds and grammar. Similarly, Tlingit (spoken in Southeast Alaska and northern British Columbia) is part of the Na-Dene family, while the Tsimshianic languages (Tsimshian, Gitxsan, Nisga’a) are often grouped under the Penutian hypothesis. The sheer number of distinct linguistic lineages underscores the long and complex prehistory of the Pacific Northwest.

These languages are not just diverse in their structure but are also deeply intertwined with the physical and spiritual landscape. The rich vocabulary for salmon species, cedar types, marine life, and weather patterns reflects an intimate understanding of the environment. Place names, often descriptive or commemorative of historical events, serve as mnemonic devices, carrying layers of cultural knowledge and ancestral claims to territory. "The language itself is a map," notes Dr. Sarah Grey, a linguist specializing in Salishan languages, "every place name tells a story, a history, a relationship to the land."

Oral Traditions: The Living Libraries

In the absence of written scripts, oral traditions became the primary means of transmitting knowledge, history, law, and spiritual beliefs. Storytelling was, and remains, a highly sophisticated art form, performed by skilled narrators who could hold audiences captive for hours, even days, with epic narratives. These stories, often featuring transformer figures like Raven or Coyote, explain the origins of the world, natural phenomena, social customs, and moral lessons. They teach about respect for the environment, the importance of community, and the consequences of greed or disrespect.

The Kwakwaka’wakw, for example, have elaborate oral histories tracing their lineage back to mythical ancestors who emerged from the sea or descended from the sky. These narratives are not mere myths but serve as charters for their social organization, their rights to resources, and their ceremonial privileges. Songs, chants, and ceremonial speeches are equally vital, imbued with spiritual power and passed down through generations. Elders, the living libraries of their communities, held immense authority, their memories safeguarding millennia of accumulated wisdom. The ability to recite accurately and with appropriate inflection was a highly valued skill, ensuring the integrity of the knowledge being transmitted.

Ceremonial Life: Weaving Community and Status

The ceremonial life of the Pacific Northwest Coastal peoples was rich and complex, epitomized by the Potlatch. This grand ceremony, found across many coastal cultures (Kwakwaka’wakw, Nuu-chah-nulth, Haida, Tlingit, Coast Salish), was far more than a feast; it was the cornerstone of social, economic, and spiritual life. A potlatch was held to mark significant life events – a birth, a marriage, a death, the raising of a totem pole, or the transfer of names and privileges. During a potlatch, the host would display their wealth and status by lavishly feasting guests and distributing vast quantities of gifts, from blankets and canoes to food and copper shields. The more generously a host gave, the higher their status rose. This system of reciprocal gift-giving ensured the redistribution of wealth and reinforced social hierarchies.

"The Potlatch was our government, our bank, our church, our school," explained Hereditary Chief Robert Joseph of the Kwakwaka’wakw Nation. "It was where we made our laws, where we taught our children, where we celebrated our lives." So powerful was the Potlatch in maintaining indigenous societies that it was banned by the Canadian government from 1884 to 1951, a desperate attempt to assimilate First Nations. Despite this suppression, it survived underground and has seen a powerful resurgence, becoming a symbol of cultural resilience and revitalization.

Other significant ceremonies include winter dances and spirit dances, where masked performers embody ancestral spirits, animals, or supernatural beings. These dances often involve elaborate regalia, drumming, and singing, creating a powerful connection to the spiritual world and reinforcing community bonds. Naming ceremonies, rites of passage, and first salmon ceremonies – rituals to honor the salmon that sustained them – further illustrate the deep spiritual connection to their environment and the cyclical nature of life.

Art and Craft: Visual Narratives

The artistic traditions of the Pacific Northwest are globally recognized for their distinctive style and profound storytelling. Totem poles, perhaps the most iconic art form, are monumental carvings that serve as visual histories, commemorating ancestors, recounting myths, displaying family crests, or marking significant events. Each figure, from Raven and Bear to Salmon and Thunderbird, holds specific meanings and tells a part of a larger narrative, often commissioned to be raised during a potlatch.

Masks are another powerful art form, intricately carved from wood and painted with vibrant colors. Used in ceremonial dances, masks transform the wearer into spiritual beings or mythical characters, bringing stories to life. The Nuu-chah-nulth, for instance, have intricate wolf masks used in their sacred ceremonies, representing power and hunting prowess.

Weaving traditions are equally rich, particularly the famous Chilkat blankets of the Tlingit and Tsimshianic peoples, characterized by their complex geometric designs and use of mountain goat wool and cedar bark. These blankets, along with Ravenstail weaving, were worn during ceremonies and conveyed status. Cedar bark, the "tree of life," was also woven into baskets, hats, and even clothing, showcasing the incredible versatility and spiritual significance of this vital resource. The distinctive formline art style, with its ovoids, U-forms, and S-forms, provides a visual language that unifies many of these artistic expressions, creating a coherent aesthetic across diverse groups.

Challenges and Resilience: The Enduring Spirit

The arrival of European settlers brought profound disruption, leading to devastating epidemics, forced displacement, and aggressive assimilation policies. The banning of the Potlatch and the imposition of residential schools, designed to strip indigenous children of their language and culture, inflicted deep wounds. Many languages faced endangerment, with some, like Chemakum, becoming extinct.

Yet, despite these immense challenges, the spirit of the Pacific Northwest Coastal peoples endures with remarkable resilience. Today, there is a powerful revitalization movement underway. Communities are working tirelessly to reclaim and restore their languages through immersion schools, master-apprentice programs, and digital resources. Elders, once silenced, are now celebrated as invaluable knowledge keepers, sharing their wisdom with eager young learners. Artistic traditions are thriving, with new generations of carvers, weavers, and dancers carrying forward the legacies of their ancestors.

The languages and traditions of the Pacific Northwest Coast are more than historical artifacts; they are living, breathing expressions of a profound cultural heritage. They speak of an intimate relationship with the land and sea, a sophisticated social order, and a spiritual worldview that continues to inspire. As these ancient voices are once again heard and celebrated, they offer invaluable lessons in ecological stewardship, community resilience, and the enduring power of cultural identity. The story of the Pacific Northwest Coast is one of survival, renewal, and the vibrant, unbreakable spirit of its First Peoples.