The Dagger in the Map: Osceola and the Unyielding Spirit of Seminole Resistance

In the annals of American history, few figures embody the fierce spirit of defiance against overwhelming odds quite like Osceola. Not a hereditary chief, but a leader forged in the crucible of injustice, his name became synonymous with the Seminole people’s unyielding resistance against forced removal from their ancestral lands in Florida. His story, a tragic yet inspiring saga of courage, strategic brilliance, and ultimate betrayal, resonates through time as a testament to the human will to remain free.

The early 19th century in the burgeoning United States was a time of aggressive expansion, driven by the ideology of Manifest Destiny and the insatiable demand for land. For the indigenous peoples of the Southeast – the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole – this meant an existential threat. The Indian Removal Act of 1830, championed by President Andrew Jackson, formalized a policy of forced relocation to lands west of the Mississippi River, a harrowing journey that would become known as the "Trail of Tears."

The Seminoles, a diverse nation forged from Creek refugees, escaped African slaves (Black Seminoles), and remnants of Florida’s earlier indigenous inhabitants, were particularly adept at living off the land and navigating the labyrinthine swamps and hammocks of their Florida home. They had already faced conflict with the United States in the First Seminole War (1817-1818), which saw General Andrew Jackson’s forces invade Spanish Florida, claiming it for the U.S. and further encroaching on Seminole territory. The Treaty of Moultrie Creek in 1823 had already confined them to a smaller reservation in central Florida, a prelude to the greater injustices to come.

It was into this volatile environment that Osceola, born sometime around 1804-1807, emerged. Known by his birth name, Billy Powell, he was of mixed Creek and European ancestry, later adopting the name Osceola, a corruption of the Creek Asi-yahola, meaning "Black Drink Singer" or "Black Drink Crier," referring to the ceremonial Black Drink consumed during tribal councils. Though not of chiefly lineage, his charisma, intelligence, and unwavering commitment to his people’s sovereignty quickly earned him immense respect and influence. He was a natural orator, his words imbued with passion and conviction, capable of rallying diverse factions within the Seminole and Black Seminole communities.

The flashpoint arrived with renewed efforts by the U.S. government to enforce the Indian Removal Act on the Seminoles. The Treaty of Payne’s Landing (1832), negotiated under dubious circumstances, purportedly committed the Seminoles to relocate. However, many Seminole leaders, including Osceola, vehemently denied its legitimacy, arguing that their true representatives had not signed it, or had signed under duress. They refused to leave.

One of the most enduring and powerful anecdotes illustrating Osceola’s defiant leadership occurred during these tense negotiations. When American Indian Agent Wiley Thompson demanded that the Seminoles sign a new treaty to confirm their removal, Osceola, reportedly, plunged his dagger into the unsigned document pinned to a map of Florida, declaring, "This is the only treaty I will ever make with the white man!" Whether this exact scene transpired or is a powerful embellishment, it perfectly encapsulates his resolute spirit and his absolute refusal to be dispossessed. He understood that the land was not merely territory; it was the foundation of their identity, their culture, and their very existence.

The Second Seminole War officially ignited on December 28, 1835. On that fateful day, Osceola, leading a small band of warriors, ambushed and killed General Wiley Thompson and a military escort outside Fort King, in retaliation for Thompson’s prior imprisonment of Osceola and his confiscation of his rifle. On the same day, in a brilliantly coordinated attack, a larger Seminole force led by Chief Micanopy and Alligator, ambushed Major Francis Dade’s command, marching from Fort Brooke to Fort King. Out of 108 U.S. soldiers, only three survived. These twin attacks sent shockwaves through the American public and marked the brutal beginning of the longest and most costly Indian war in U.S. history.

Osceola’s leadership throughout the war was characterized by strategic brilliance and an intimate understanding of the Florida terrain. He masterminded devastating guerrilla tactics, utilizing the dense swamps and hammocks to their advantage. Seminole warriors, often outnumbered and outgunned, would launch surprise attacks, melt back into the wilderness, and strike again when least expected. Their mobility and knowledge of the environment frustrated successive U.S. generals, who found their conventional military strategies ineffective against such an elusive and determined foe.

His leadership extended beyond the battlefield. Osceola was a unifying force, bridging the sometimes-strained relationships between various Seminole bands and, crucially, fostering a powerful alliance with the Black Seminoles. These maroons, many of whom had escaped slavery on southern plantations, fought with particular ferocity, knowing that surrender meant re-enslavement. Osceola understood their plight and recognized their invaluable contribution to the resistance, treating them as equals in the fight for freedom. This alliance proved to be one of the most formidable aspects of the Seminole resistance, a testament to Osceola’s inclusive vision.

For nearly two years, Osceola remained an elusive and inspiring figure. His reputation grew, not just among his own people, but also among the American public, who were increasingly fascinated by the "war chief" who defied their government. He became a symbol of noble savagery to some, and a formidable, cunning adversary to others. But to the Seminoles, he was a beacon of hope, a warrior who embodied their collective will to resist.

However, the war of attrition began to take its toll. Despite their successes, the Seminoles were fighting against a nation with vastly superior resources. The U.S. Army, under the command of General Thomas Jesup, began to adopt more ruthless tactics, destroying Seminole villages, crops, and hunting grounds, aiming to starve them into submission.

It was under these desperate circumstances that the darkest chapter of Osceola’s story unfolded. In October 1837, under a flag of truce, Osceola and a delegation of Seminole leaders came to Fort Peyton, near St. Augustine, for negotiations with General Jesup. They had been assured safe passage and a genuine opportunity for parley. However, Jesup, frustrated by the war’s protraction and the elusive nature of his enemy, ordered their immediate arrest. This act of betrayal, a flagrant violation of military protocol and international law, was met with outrage even within the U.S. military and public.

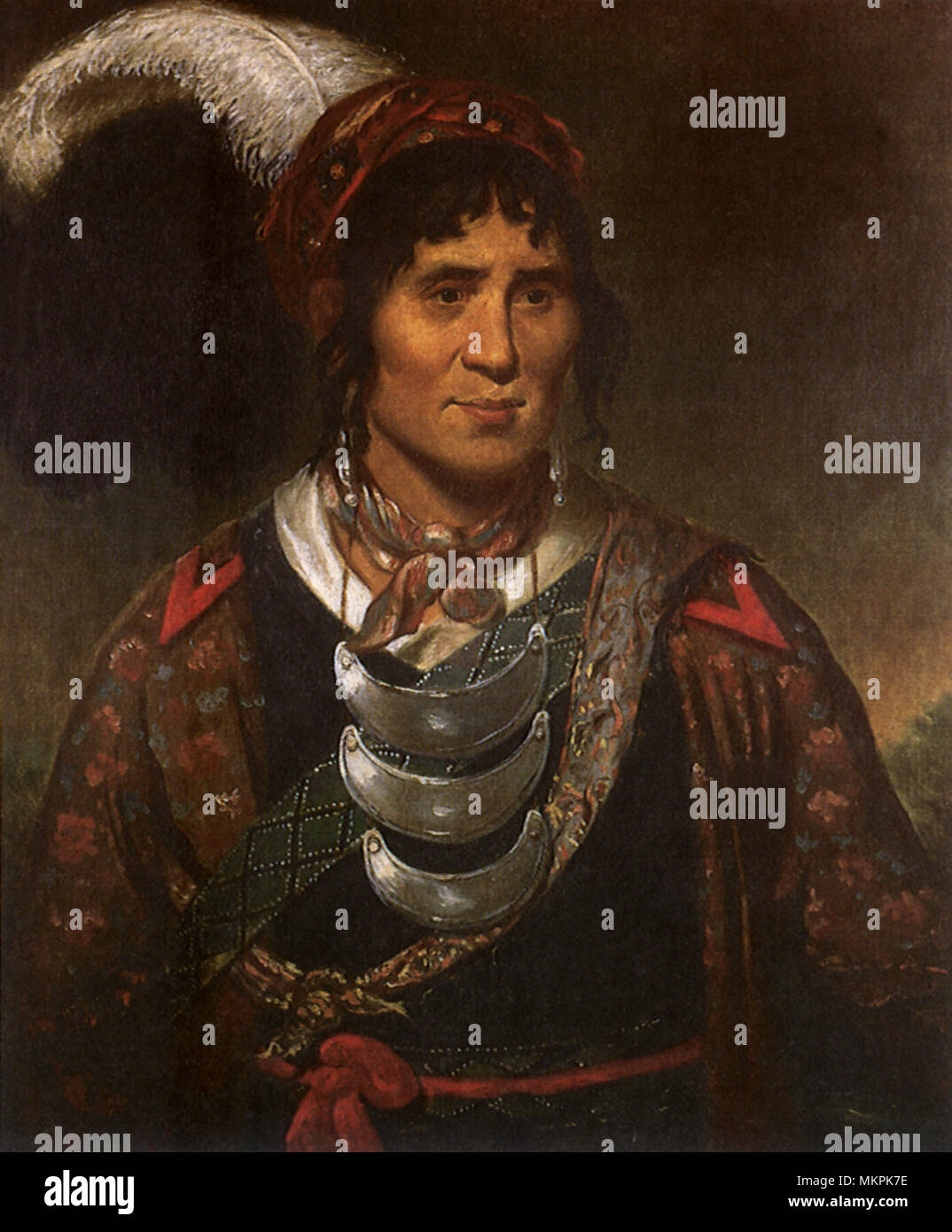

Osceola was imprisoned first at Fort Marion (now Castillo de San Marcos) in St. Augustine, then transferred to Fort Moultrie, near Charleston, South Carolina. Even in captivity, his spirit remained unbroken. His dignified bearing captivated many, including the renowned artist George Catlin, who painted several iconic portraits of Osceola during his imprisonment. These portraits capture his piercing gaze, his proud features, and the profound sorrow of a man unjustly stripped of his freedom, yet unbowed. Catlin described him as "a most extraordinary character… a warrior and a statesman… a man of great mind and a true patriot."

Sadly, Osceola’s health, already weakened by the hardships of war, rapidly deteriorated in confinement. He succumbed to malaria or a throat infection (quinsy) on January 30, 1838, at Fort Moultrie. He was only in his mid-30s. His death, however, was not the end of his indignities. In a grotesque act that highlights the prevailing attitudes of the time, the post surgeon, Dr. Frederick Weedon, decapitated Osceola’s body, keeping his head as a trophy. This macabre act, a final violation, became another dark stain on the U.S. government’s treatment of its indigenous adversaries.

Though Osceola was gone, his spirit of resistance lived on. The Second Seminole War continued for several more years, fueled by the memory of his betrayal and the enduring desire for freedom. Leaders like Coacoochee (Wild Cat) and Billy Bowlegs continued to wage guerrilla warfare, ensuring that Florida would remain a battleground for over a decade. The U.S. government ultimately spent over $40 million (an astronomical sum at the time) and lost thousands of lives, a testament to the tenacity of the Seminole people. In the end, many Seminoles were forcibly removed, but a significant number, perhaps a few hundred, remained hidden in the Everglades, never formally surrendering, their descendants forming today’s Seminole Tribe of Florida and Miccosukee Tribe of Indians of Florida.

Osceola’s legacy extends far beyond the swamps of Florida. He remains a powerful symbol of indigenous sovereignty, integrity, and the enduring human spirit in the face of oppression. His defiance against overwhelming power, his strategic acumen, and his unwavering commitment to his people’s land and liberty serve as an inspiration for indigenous rights movements and anti-colonial struggles worldwide. He was a leader who understood that true freedom was not negotiable, and his life, though tragically cut short, stands as an eternal beacon of the unconquered spirit. The dagger he plunged into the map of Florida left an indelible mark, symbolizing a profound rejection of injustice that continues to resonate with clarity and power today.