Black Gold and Blood: The Enduring Saga of the Osage Nation’s Oil Wealth

The story of the Osage Nation is a profound and often harrowing chapter in American history, a narrative steeped in displacement, immense wealth, and unimaginable tragedy. It is a testament to Indigenous resilience, a stark illustration of the corrosive power of greed, and a reminder of the enduring fight for sovereignty and justice. From their ancestral lands in the Ohio Valley to the rolling hills of present-day Oklahoma, the Osage journey is one defined by a unique and fateful decision that would transform their destiny: the retention of their subsurface mineral rights. This act of foresight, born from generations of forced removal and broken treaties, would soon make them, per capita, the wealthiest people in the world, yet also cast them into a crucible of exploitation and murder that reverberates to this day.

The Osage, a powerful and sophisticated Siouan-speaking people, once commanded a vast territory stretching across what is now Missouri, Kansas, Arkansas, and Oklahoma. Their society was highly structured, based on hunting bison and cultivating crops, governed by a dual leadership system and rich spiritual traditions. However, the relentless westward expansion of European settlers and the U.S. government’s aggressive policies of Indian Removal chipped away at their domain. Through a series of treaties in the early 19th century, the Osage ceded millions of acres, each agreement further reducing their lands.

By 1870, facing intense pressure and a shrinking land base, the Osage made a pivotal decision. Rather than accept yet another government-mandated reservation in Indian Territory, they chose to purchase their own land. They sold their remaining Kansas reservation lands and used the proceeds to buy 1.47 million acres in what would become Osage County, Oklahoma, from the Cherokee Nation. Crucially, their leaders, having learned bitter lessons from past treaties where their land was taken and then exploited, insisted on a unique clause: the Osage Nation would retain collective ownership of all subsurface mineral rights. This was a radical move at the time, an act of astute negotiation that would soon prove to be their salvation and, paradoxically, their curse.

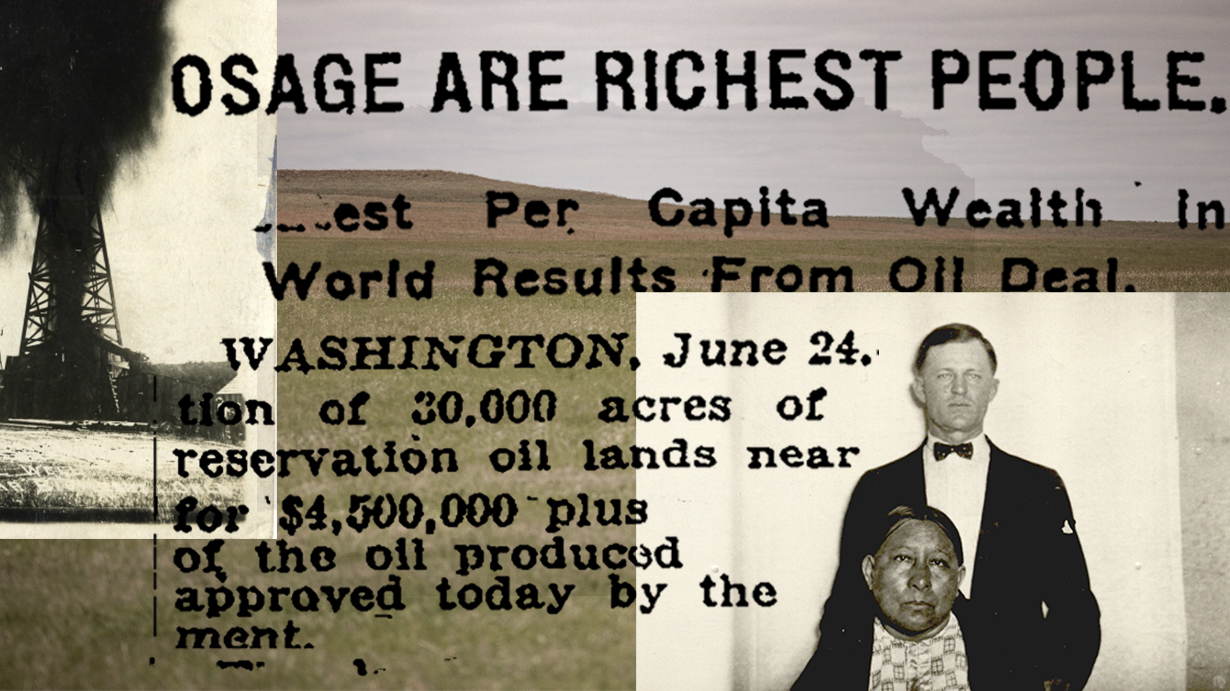

The early 20th century brought the roaring discovery of oil beneath the Osage lands. The vast petroleum reserves, part of the Mid-Continent Oil Field, turned their quiet reservation into a maelstrom of derricks, pipelines, and boomtowns overnight. Suddenly, the Osage Nation was sitting atop an ocean of "black gold." The income generated from oil and gas leases and royalties was distributed directly to the Osage people through a system of "headrights." Each enrolled Osage received one headright, granting them an equal share of the mineral trust income. By the 1920s, the Osage Nation was receiving millions of dollars annually, making its members the richest people per capita in the world.

Newspapers of the era sensationalized their wealth, depicting Osage families driving luxury cars, living in grand mansions, and employing white servants. They sent their children to prestigious boarding schools, wore designer clothes, and participated in a burgeoning consumer culture. This sudden affluence, however, was viewed with a mixture of awe, envy, and thinly veiled racism by the surrounding white population. Many couldn’t fathom how "savages" could manage such wealth, leading to a pervasive belief that the Osage were incapable of handling their own finances.

This racist perception provided the pretext for the U.S. Congress to pass legislation in 1921, establishing a paternalistic "guardianship system." Under this system, many Osage individuals, particularly those deemed "incompetent" by a local court – often for no other reason than their Osage heritage – were assigned white guardians to manage their headright income. These guardians, often prominent local businessmen, attorneys, or politicians, were supposed to protect the Osage’s interests. In reality, the system became a legal framework for widespread fraud and exploitation. Guardians routinely embezzled funds, overcharged for services, and manipulated their wards’ finances, often leaving them in poverty while pocketing fortunes.

But the exploitation escalated to a far more sinister level, ushering in what became known as the "Reign of Terror." Between 1918 and 1931, an estimated 60 or more Osage men, women, and children died under mysterious circumstances. Their deaths were often attributed to "wasting disease," alcohol poisoning, or suspicious accidents, but the true motive was clear: to inherit their valuable headrights. Under the law, headrights could be inherited by legal heirs, regardless of their ethnicity. This created a deadly incentive for unscrupulous individuals to marry into Osage families, then systematically murder their Osage spouses and relatives to consolidate control over their wealth.

The most infamous example of this reign of terror centered around the family of Mollie Burkhart. Her sister, Anna Brown, disappeared and was later found shot in the head. Another sister, Rita Smith, and her husband Bill, were killed when their house exploded. Mollie herself became gravely ill, poisoned over time. The mastermind behind these gruesome crimes, and many others, was revealed to be William K. Hale, a powerful and supposedly benevolent cattleman known as the "King of the Osage Hills." Hale had systematically orchestrated the murders of Mollie’s family members, including through his nephew Ernest Burkhart, Mollie’s husband, all to gain control of their headrights.

Local law enforcement, often corrupt or complicit, proved unwilling or unable to investigate these crimes effectively. The Osage Nation appealed to the federal government for help. Their pleas eventually reached the nascent Bureau of Investigation (BOI), the precursor to the FBI, under its ambitious director, J. Edgar Hoover. Hoover dispatched a team of undercover agents, led by the tenacious Tom White, a former Texas Ranger. These agents, posing as cattle buyers and insurance salesmen, slowly pieced together the intricate web of conspiracy, intimidation, and murder. Their investigation was groundbreaking, marking one of the FBI’s first major homicide cases. Eventually, Hale, Ernest Burkhart, and several accomplices were arrested, tried, and convicted for their heinous crimes, though many other murders remained unsolved.

The Reign of Terror exposed the profound vulnerabilities of the Osage people, highlighting the systemic racism and greed that allowed such atrocities to flourish. It also sparked a renewed push for Osage self-determination. Over the subsequent decades, the Osage fought tirelessly to regain control over their affairs. The guardianship system was eventually dismantled, and the Osage Nation began to rebuild its governmental structures, asserting its inherent sovereignty.

Today, the Osage Nation stands as a vibrant and resilient sovereign nation. While the headright system still exists, it is now primarily confined to Osage descendants, ensuring that the wealth remains within the community. The Nation actively manages its mineral estate, investing in its people through education, healthcare, and cultural preservation programs. They operate their own government, courts, and police force, and have diversified their economy beyond oil, with ventures in gaming, tourism, and other industries.

The legacy of the oil boom and the Reign of Terror remains a powerful part of the Osage identity. It is a story of profound loss and trauma, but also of incredible strength and endurance. The Osage have used their experiences to inform their present and future, emphasizing the importance of cultural continuity, language revitalization, and protecting their heritage. David Grann’s bestselling book, Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI, and Martin Scorsese’s recent film adaptation, have brought this crucial history to a global audience, ensuring that the Osage story is not forgotten.

The Osage Nation’s journey from their ancestral lands to the oil fields of Oklahoma is a powerful narrative of survival, adaptation, and an unwavering commitment to their cultural identity. It serves as a potent reminder of the complex and often brutal history of Indigenous peoples in America, a history where immense wealth could bring both prosperity and peril, but where the human spirit, ultimately, found a way to endure and reclaim its destiny. Their story is not just a chapter in the past; it is a living testament to the ongoing struggle for justice and self-determination that continues to shape the future of Indigenous nations worldwide.