Okay, here is a 1200-word journalistic article in English on "Oral History Transmission in Indigenous Cultures."

Echoes of Eternity: The Enduring Power of Oral History in Indigenous Cultures

In a world increasingly defined by the written word, by databases and digital archives, the profound and vibrant tradition of oral history transmission within indigenous cultures stands as a testament to human ingenuity, resilience, and the enduring power of memory. Far from being mere anecdotes or folklore, these oral traditions represent intricate, living knowledge systems – encyclopedias of law, medicine, spirituality, history, land management, and identity – meticulously preserved and passed down across countless generations.

For indigenous peoples globally, from the Inuit of the Arctic to the Māori of Aotearoa (New Zealand), the Aboriginal Australians, and the countless Native American nations, oral history is the bedrock of their societies. It is the primary means by which cultural memory is sustained, values are instilled, and collective identity is forged. This isn’t just about recounting events; it’s about embodying a worldview, a way of being that connects past, present, and future in a continuous, sacred tapestry.

More Than Just Stories: A Holistic Knowledge System

To understand oral history in indigenous contexts, one must first shed the Western-centric notion that history solely resides in written documents. "Our history is written in the land, in the stars, in our songs, and in the hearts of our people," explains Elder William Commanda, an Algonquin spiritual leader. "It is a living history, not something confined to a book on a shelf." This perspective underscores the holistic nature of indigenous knowledge. Oral traditions often interweave various forms of expression: spoken narratives, ceremonial dances, intricate songs, visual arts, and even landscape features that serve as mnemonic devices.

Take, for instance, the "songlines" of Aboriginal Australians. These are not merely routes across the land but complex navigational maps embedded with stories, laws, and ecological knowledge, passed down through generations via songs. Each verse describes a particular landmark, a plant, an animal, or a mythological event, effectively mapping vast territories and their resources. These songlines are living archives, demonstrating an unparalleled integration of geography, history, and culture.

Similarly, the whakapapa (genealogy) of the Māori people is a powerful example. Recited through intricate chants and narratives, whakapapa connects individuals to their ancestors, their land, and their spiritual heritage, defining their identity, rights, and responsibilities within the community. It’s a living chain that stretches back to the mythical origins of the world, constantly reinforced and re-affirmed through performance and communal sharing.

The Mechanisms of Transmission: Elders as Living Libraries

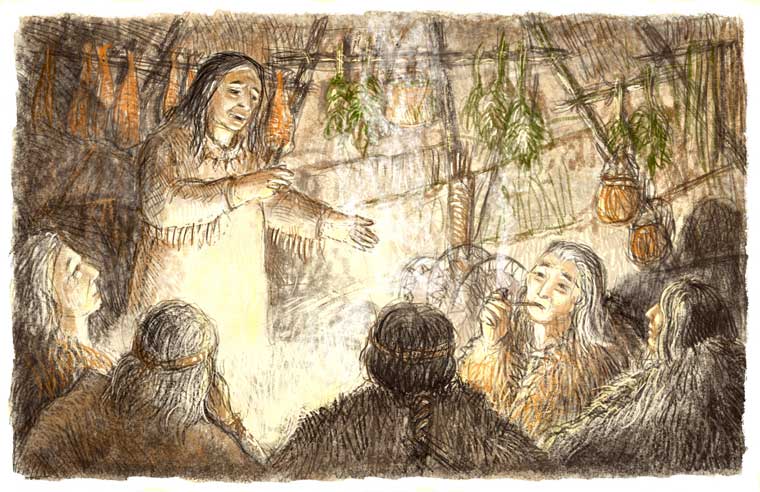

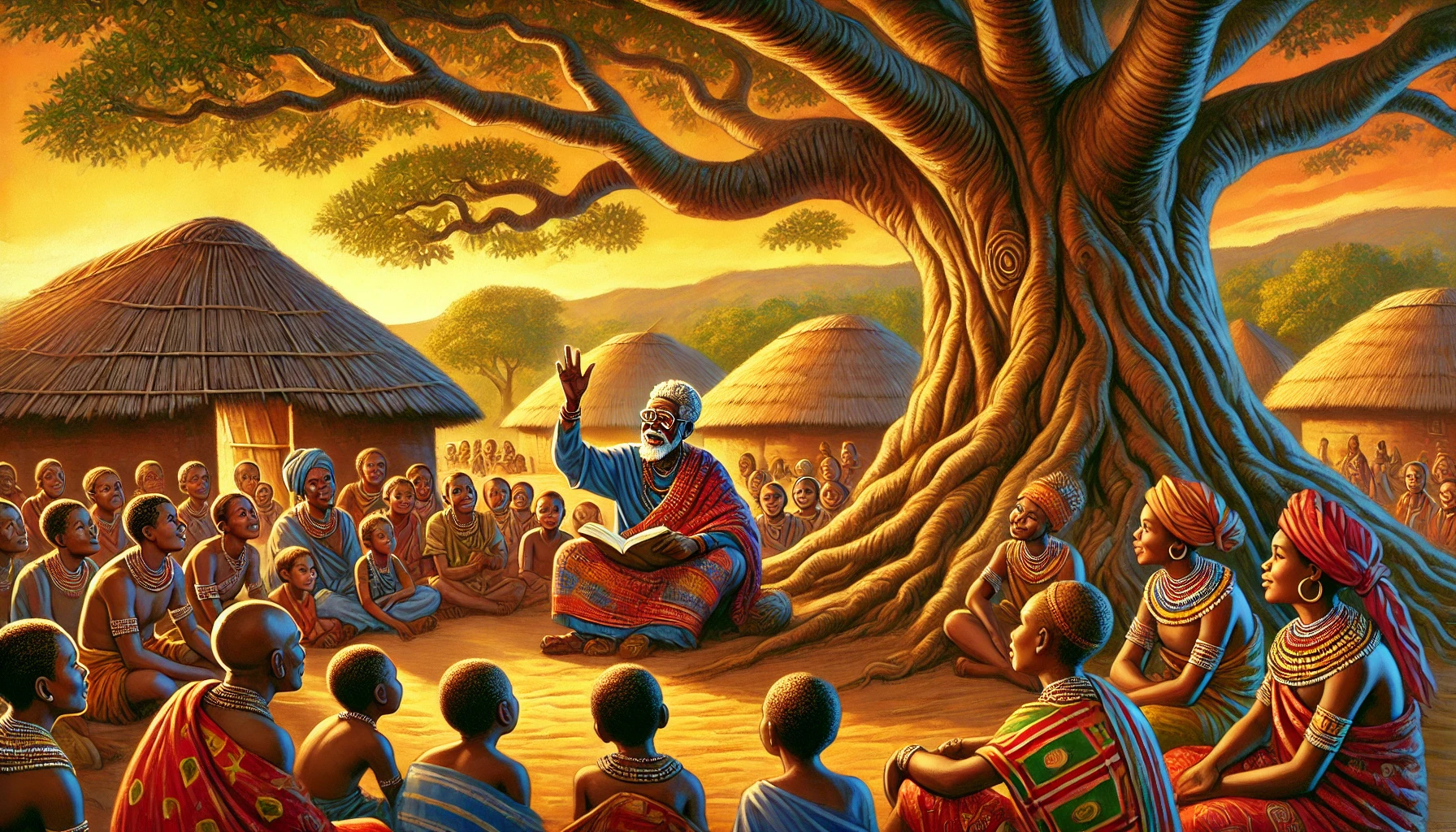

The transmission of oral history is a highly sophisticated and intentional process, not a casual recounting. It often involves dedicated elders – revered as "living libraries" – who bear the immense responsibility of memorizing, preserving, and accurately transmitting vast amounts of information. This process can begin in early childhood, with children learning foundational narratives and songs, gradually progressing to more complex and sacred knowledge as they mature and demonstrate readiness and respect.

"We don’t just tell stories; we teach," says a Navajo grandmother, whose name translates to "She Who Weaves Wisdom." "Each story has layers, like an onion. What you learn as a child is different from what you learn as an adult. It’s about readiness, about understanding the deeper meaning, the moral, the law, the warning."

Apprenticeship models are common, where a younger individual is chosen by an elder to specifically learn and carry forward particular bodies of knowledge. This often involves years, even decades, of intensive listening, memorization, observation, and practice, under the elder’s careful guidance. The learner is expected not just to repeat but to embody the knowledge, understanding its context, its spirit, and its practical application.

Ceremonies and rituals play a crucial role in reinforcing and re-enacting oral traditions. These events provide structured environments for the collective retelling of origin stories, historical accounts, and legal precedents, often accompanied by specific dances, songs, and visual elements that aid in memorization and emotional resonance. The communal nature of these transmissions strengthens collective memory and ensures accuracy through shared experience.

The Content: A Repository of Indigenous Ingenuity

The scope of knowledge preserved through oral history is breathtakingly vast:

- Creation Narratives and Spirituality: Explaining the origins of the universe, humanity, and the natural world, often imbuing landscapes with sacred meaning.

- Historical Accounts: Documenting migrations, conflicts, alliances, and significant events, often with astonishing accuracy when later compared to archaeological or anthropological findings.

- Legal Systems and Governance: Outlining traditional laws, protocols, and methods of conflict resolution, essential for maintaining social order. The Great Law of Peace of the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Confederacy, which influenced aspects of the US Constitution, was entirely an oral tradition for centuries.

- Ethnobotany and Medicine: Detailed knowledge of plants, their uses, preparation, and medicinal properties, accumulated over millennia.

- Environmental Knowledge: Sophisticated understanding of local ecosystems, weather patterns, animal behavior, and sustainable land management practices.

- Navigation and Astronomy: Complex systems for navigating vast territories or oceans using stars, currents, and natural landmarks. The celestial knowledge of Polynesian navigators, for example, allowed them to traverse immense stretches of the Pacific.

Challenges and Threats: A Legacy of Disruption

Despite their inherent strength, indigenous oral traditions have faced immense threats, primarily stemming from colonialism, forced assimilation, and the rapid pace of modernization.

The imposition of foreign languages, religions, and education systems actively suppressed indigenous languages – the very vessels of oral history. Children were often forbidden from speaking their native tongues in residential schools, punished severely for doing so. This severed intergenerational links, creating "silent generations" who, though they understood their language, were reluctant or unable to transmit it due to trauma and the lack of opportunity.

"When our language goes, a whole world goes with it," laments a Cree elder. "It’s not just words; it’s the way we think, the way we see the world, the way we relate to each other and to the land." The loss of indigenous languages directly correlates with the erosion of oral traditions and the unique knowledge embedded within them. According to UNESCO, nearly half of the world’s approximately 7,000 languages are endangered, with indigenous languages being disproportionately affected.

Urbanization and the shift away from traditional lifestyles also pose challenges. As communities disperse and younger generations move away from ancestral lands, the daily, immersive context for learning oral histories diminishes. The constant bombardment of modern media and distractions can also make it harder for youth to dedicate the time and focus required for deep oral learning.

Resilience and Revitalization: A New Chapter

Yet, indigenous communities are fiercely resilient, and efforts to revitalize oral history transmission are gaining momentum globally. Language revitalization programs, often spearheaded by elders and passionate community members, are at the forefront. "Language nests" (like the Te Kōhanga Reo in New Zealand) immerse young children in their native language from birth, while adult immersion programs help reclaim lost tongues.

Cultural camps and intergenerational workshops bring elders and youth together, creating dedicated spaces for storytelling, singing, and the direct transfer of knowledge. These initiatives not only teach history but also foster a renewed sense of pride, identity, and connection among younger generations. Technology, once seen as a threat, is now being cautiously embraced as a tool. Digital archives, recorded interviews with elders, and online language resources are being developed, always with strict protocols for community ownership and cultural sensitivity to prevent misuse or decontextualization.

"We are using new tools to preserve ancient wisdom," says a young Inuit scholar working on a digital archive of Unipkaat (traditional narratives). "But the goal is not to replace the elder; it’s to support them, to ensure that the knowledge they carry can reach those who are ready to learn, especially when our elders are fewer."

The Broader Significance: Lessons for All Humanity

The ongoing vitality of oral history transmission in indigenous cultures offers invaluable lessons for all humanity. It reminds us of the power of collective memory, the importance of intergenerational wisdom, and the limitations of purely textual forms of knowledge. It highlights alternative epistemologies – ways of knowing – that prioritize holistic understanding, interconnectedness, and a deep respect for the natural world.

As the world grapples with climate change, social fragmentation, and a search for sustainable ways of living, the ancient wisdom embedded in indigenous oral traditions offers profound insights. These histories contain blueprints for living in harmony with the environment, for fostering strong communities, and for cultivating a sense of purpose rooted in deep cultural connection.

The echoes of eternity, carried on the winds of stories, songs, and ceremonies, continue to resonate within indigenous cultures. They are not relics of the past but living, breathing testaments to survival, identity, and an enduring wisdom that continues to guide, teach, and inspire. Protecting and honoring these traditions is not just about preserving indigenous heritage; it is about enriching the collective human story, ensuring that these invaluable voices continue to be heard for generations to come.