Certainly, here is a 1200-word journalistic article in English about the Oklahoma Native American Nations Map, incorporating relevant facts and quotes.

The Unfolding Map: How Oklahoma’s Native Nations Are Reclaiming Their Sovereign Landscape

By

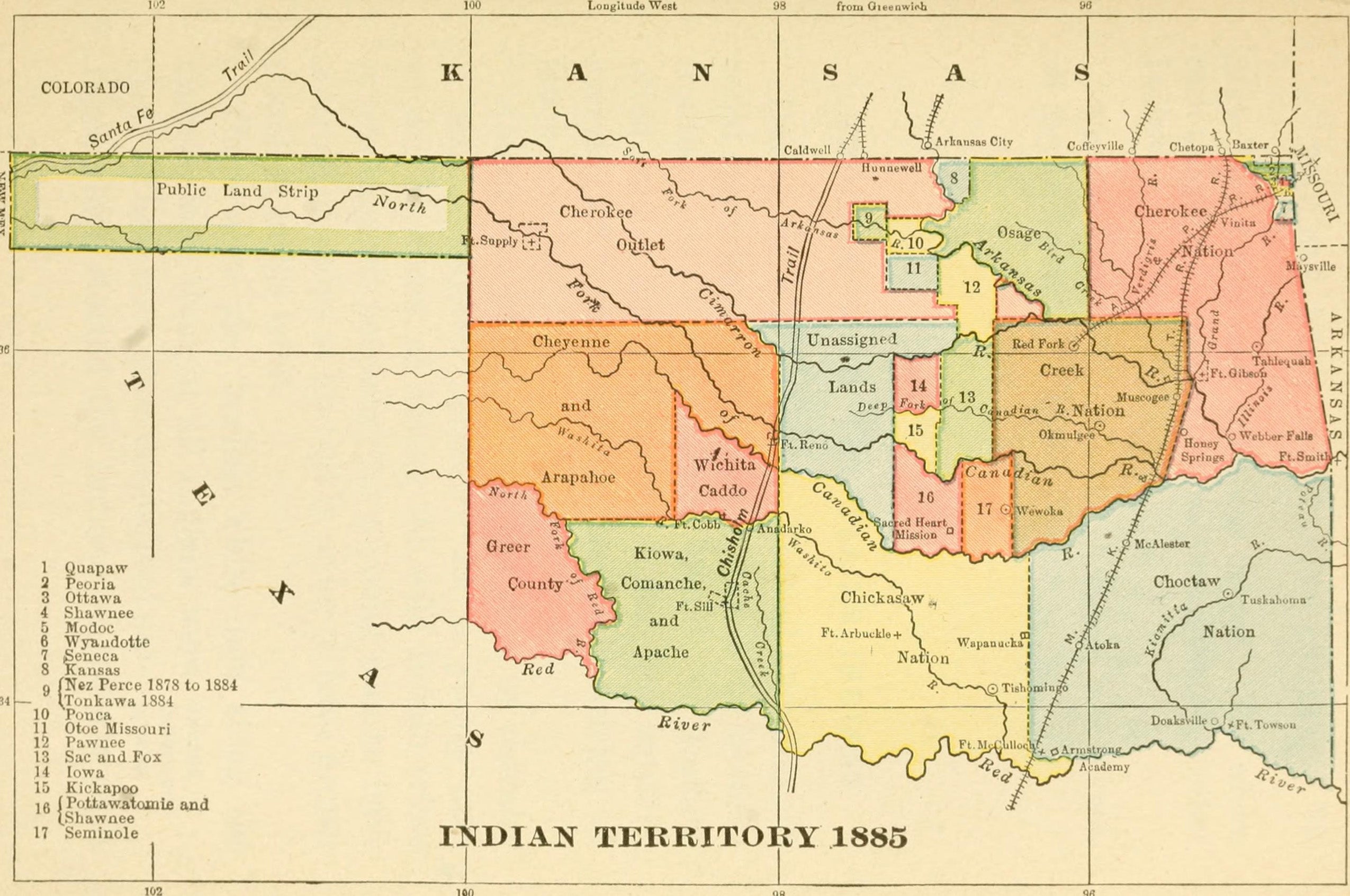

For generations, the map of Oklahoma has been a study in a deliberate erasure. What was once "Indian Territory," a vast expanse promised to dozens of Native American nations removed from their ancestral lands, was systematically dismantled by U.S. policy, culminating in the 1907 statehood of Oklahoma. The reservations, once clearly delineated, faded into the background of state and county lines, becoming, for many, mere historical footnotes.

But in 2020, a landmark Supreme Court decision, McGirt v. Oklahoma, dramatically redrew that mental map, affirming that much of eastern Oklahoma – roughly 43% of the state’s landmass – remains Native American reservation land. This wasn’t a creation of new territory, but a powerful affirmation of promises made long ago, promises the Court declared "must be kept." The decision has ignited a profound reevaluation of sovereignty, jurisdiction, and identity, forcing both Native nations and the state of Oklahoma to grapple with an unfolding, dynamic landscape where the lines of governance are once again vibrant and visible.

A History Forged in Removal and Resilience

To understand the current map, one must journey back to the early 19th century. The forced removal policies of the U.S. government, epitomized by the Trail of Tears, drove the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole Nations – often collectively called the "Five Civilized Tribes" – along with dozens of other tribes, to what was then designated Indian Territory. Here, they were promised permanent homelands, free from state interference, where they could rebuild their societies, establish constitutional governments, and preserve their cultures.

For decades, they did just that. They created sophisticated legal systems, schools, newspapers, and economies. The map of Indian Territory was a patchwork of distinct, self-governing nations. However, this autonomy was short-lived. The insatiable demand for land, coupled with the ideology of assimilation, led to a series of federal acts designed to dismantle tribal sovereignty and open the territory for non-Native settlement.

The Dawes Act of 1887 and subsequent legislation, particularly the Curtis Act of 1898, forcibly allotted communal tribal lands to individual tribal members, with the "surplus" lands then sold off to settlers. Tribal governments were dissolved, and their judicial systems were superseded. When Oklahoma achieved statehood in 1907, Indian Territory was officially absorbed, and the reservation boundaries, though never formally disestablished by Congress, effectively vanished from public consciousness and state administration.

"For over a century, the common understanding was that tribal reservations in Oklahoma had ceased to exist," explains Dr. Lindsey Claire Smith, a historian specializing in Native American studies at Oklahoma State University. "This narrative served a specific political and economic purpose, allowing the state to assert broad jurisdiction. But legally, that understanding was flawed, as McGirt ultimately confirmed."

The McGirt Bombshell: Promises Must Be Kept

The McGirt case originated with Jimcy McGirt, a member of the Seminole Nation, who was convicted in state court of sex crimes committed on the Muscogee (Creek) Nation’s reservation. McGirt argued that the state lacked jurisdiction over his case because, as a Native American, his crimes occurred on reservation land, and thus fell under federal or tribal jurisdiction, not state.

The Supreme Court, in a 5-4 decision authored by Justice Neil Gorsuch, agreed. The core of the ruling was simple: only Congress has the power to disestablish a reservation, and Congress had never done so for the Muscogee (Creek) Nation. Therefore, the reservation, encompassing much of Tulsa and surrounding areas, still existed.

"On the far end of the Trail of Tears was a promise," Gorsuch wrote for the majority. "The United States promised the Creek Nation a reservation where it could govern itself… Today, we are asked whether that promise still holds. To rule for Oklahoma, we would have to say the United States broke the promise. We refuse to do so."

The implications were immediate and profound. While McGirt specifically addressed the Muscogee (Creek) Nation, subsequent rulings by the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals extended the principle to the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, and Seminole Nations – the other "Five Civilized Tribes" – covering approximately 19 million acres, or nearly half of Oklahoma. With 39 federally recognized tribes, Oklahoma is home to the largest number of Native American nations in any single state, and many more are now asserting their existing reservations.

A Map of Living Sovereignty

The "Oklahoma Native American Nations Map" is not just a historical relic; it is a dynamic, living document shaping the present and future. It signifies:

-

Restored Jurisdictional Authority: Tribal nations are exercising their inherent authority over crimes committed by or against Native Americans within their reservation boundaries. This has led to a dramatic expansion of tribal law enforcement, judicial systems, and prosecution offices. The Cherokee Nation, for example, saw its caseload increase by over 2,000% in the immediate aftermath of McGirt, requiring massive investment in justice infrastructure. "We’re building out our justice system at an unprecedented pace," stated Cherokee Nation Principal Chief Chuck Hoskin Jr. in a public address. "This isn’t just about law enforcement; it’s about ensuring justice for our citizens on our own terms."

-

Economic Empowerment: The clarity of reservation boundaries strengthens tribal governments’ ability to engage in economic development, negotiate with federal agencies, and manage natural resources. Tribal enterprises, already significant contributors to Oklahoma’s economy through casinos, healthcare, and manufacturing, now operate with clearer sovereign footing. This fosters greater self-sufficiency and reinvestment in tribal communities. The Choctaw Nation, a major employer in southeastern Oklahoma, continues to expand its diverse business portfolio, leveraging its strengthened sovereign position.

-

Cultural Revitalization: The renewed emphasis on sovereignty reinforces tribal identity and cultural preservation efforts. Language immersion programs, traditional ceremonies, and educational initiatives gain new impetus when the physical and legal landscape reaffirms the distinct existence of Native nations. The Chickasaw Nation, for instance, has long been a leader in cultural preservation, operating museums, cultural centers, and language programs that are now intrinsically linked to the geographical reality of their reservation.

-

Complex Intergovernmental Relations: The unfolding map necessitates intricate negotiations and cooperation between tribal governments, the state of Oklahoma, and federal agencies. While initial reactions from the state were often contentious, there has been a growing understanding of the need for intergovernmental agreements on issues ranging from criminal justice to environmental regulation and taxation. These agreements are crucial for creating a seamless system of governance across the state. "It’s about finding common ground and building bridges, not walls," said a state official involved in post-McGirt negotiations, emphasizing the shared interest in public safety and economic stability.

Challenges and the Path Forward

Despite the transformative nature of McGirt, significant challenges remain. The sudden shift in jurisdiction has created a "checkerboard" effect, where the legal authority for a crime can depend on the race of the individuals involved and the specific location within a reservation boundary. This complexity requires ongoing coordination and resource allocation.

Funding for tribal justice systems is a critical issue. While federal support exists, the dramatic increase in caseloads demands substantial and sustained investment. Public education is also paramount; many Oklahomans, Native and non-Native alike, are still grappling with the implications of the decision and the true nature of tribal sovereignty.

However, the opportunities presented by this unfolding map far outweigh the challenges. It represents a chance to rectify historical injustices, strengthen self-determination, and foster a more equitable and prosperous future for all Oklahomans. The Native American nations of Oklahoma are not just historical entities; they are vibrant, modern governments contributing significantly to the social, cultural, and economic fabric of the state.

The Oklahoma Native American Nations Map is no longer a faded memory. It is a bold, living testament to resilience, a testament to promises kept, and a vibrant blueprint for a future where distinct sovereign nations coexist, collaborate, and thrive within a shared landscape. As the lines of this map continue to unfold, they tell a powerful story of endurance, justice, and the enduring spirit of Native America.