The Enduring Heartbeat of Gichigami: A Journey Through Ojibwe History in the Great Lakes

The Great Lakes region, a vast expanse of freshwater seas, ancient forests, and winding rivers, pulses with a history far deeper than any European map suggests. For millennia, this land has been the ancestral home of the Anishinaabeg, a diverse group of Algonquian-speaking peoples, among whom the Ojibwe (also known as Chippewa) stand as a cornerstone. Their story is one of profound connection to the land, remarkable adaptability, enduring resilience, and a continuous struggle for sovereignty and cultural preservation against overwhelming odds.

To truly understand the Ojibwe is to understand Gichigami – the Great Sea, Lake Superior – and the intricate network of waterways that define their traditional territory, stretching from present-day Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota, west into the plains of North Dakota, and north across Ontario and Manitoba. Their history is not a relic of the past, but a living, breathing narrative woven into the very fabric of this landscape.

The Ancient Roots: Prophecy, Migration, and a Sustainable Way of Life

Ojibwe oral traditions speak of a great migration, guided by the Seven Fires Prophecy. This ancient prophecy foretold of a westward journey from the Atlantic coast, following a sacred shell (miigis) that appeared in the sky, stopping where "food grows on water." This "food" was manoomin, or wild rice, which proliferates in the shallow waters of the Great Lakes’ wetlands. This prophecy not only explains their geographical distribution but also underscores their spiritual and practical relationship with the land.

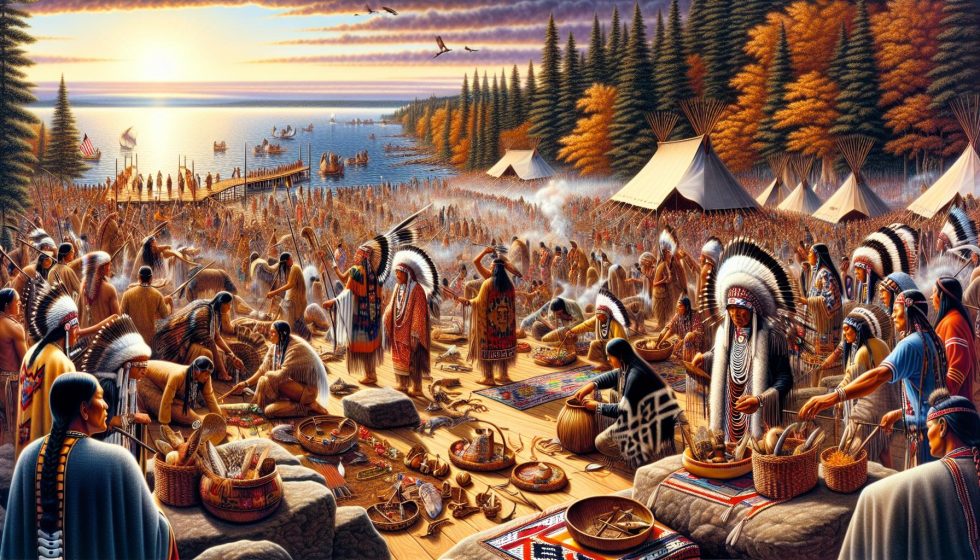

Before European contact, Ojibwe society was highly organized, deeply spiritual, and remarkably self-sufficient. Their seasonal rounds were dictated by the rhythms of nature. Spring brought the tapping of maple trees for sugar, a vital sweetener and preservative. Summer saw the planting of corn, beans, and squash in fertile garden plots, along with extensive fishing in the abundant lakes and rivers. Fall was dedicated to the crucial wild rice harvest, a communal activity that cemented social bonds and provided a staple for winter. Winters were times for hunting moose, deer, and small game, trapping fur-bearing animals, and storytelling.

Their technological innovations were perfectly attuned to their environment. The wiigwaas jiimaan (birch bark canoe) was a marvel of engineering: lightweight, durable, and capable of navigating both shallow streams and the vast open waters of the Great Lakes. Birch bark also provided material for their homes (wiigwaam), containers, and even sacred scrolls used in the Midewiwin, the Grand Medicine Society, a central spiritual and healing institution that preserved knowledge, ceremonies, and moral teachings. "Our canoes were not just vessels," an elder might say, "they were extensions of our bodies, connecting us to every part of our world."

The Age of Contact: Trade, Alliances, and Shifting Sands

The arrival of Europeans in the 17th century irrevocably altered the trajectory of Ojibwe history. The French, primarily driven by the lucrative fur trade, were the first to establish significant contact. The Ojibwe quickly became key players, acting as skilled hunters, trappers, and vital intermediaries in the vast trade networks that stretched across the continent. They exchanged furs, particularly beaver pelts, for European goods like metal tools, firearms, blankets, and glass beads.

This initial period was characterized by a complex, often respectful, relationship. The French, unlike later European powers, largely viewed Indigenous nations not as subjects, but as independent allies and trading partners. The Ojibwe formed crucial military alliances with the French against their common rivals, particularly the Iroquois Confederacy, which allowed them to expand their territory westward. However, European contact also brought devastating diseases like smallpox and measles, against which Indigenous peoples had no immunity, leading to catastrophic population declines.

As the geopolitical landscape shifted, so too did the Ojibwe’s alliances. After the British defeated the French in the Seven Years’ War (French and Indian War) in 1763, the Ojibwe found themselves negotiating with a new, more aggressive power. British and later American expansionism brought an insatiable demand for land, leading to increasing pressure on Ojibwe territories.

The Era of Treaties and Dispossession: A Clash of Worldviews

The 19th century marked a dark and transformative period. As the United States aggressively pursued its policy of "Manifest Destiny," the Ojibwe, like many other Indigenous nations, faced relentless pressure to cede their ancestral lands through a series of treaties. From the early 1800s through the mid-1800s, treaties such as the Treaty of St. Peters (1837), the Treaty of La Pointe (1842), and the Treaty of La Pointe (1854) saw the Ojibwe cede millions of acres of prime timber, mineral, and agricultural lands in exchange for meager annuities, goods, and the establishment of reservations.

These treaties, often negotiated under duress, with language barriers, and with a fundamentally different understanding of land ownership, were a classic clash of worldviews. For the Ojibwe, land was not something to be "owned" and sold outright; it was a sacred trust, a source of life, to be shared and stewarded. The concept of "ceding" land often meant granting access or shared use, not absolute relinquishment. Crucially, in many of these treaties, the Ojibwe reserved their rights to hunt, fish, and gather on the ceded territories – rights that would become the cornerstone of future legal battles.

The establishment of reservations, while providing a small refuge, was also part of a larger federal policy of assimilation. The goal was to dismantle traditional Ojibwe governance, culture, and economy, forcing them to adopt American farming practices, Christianity, and the English language.

The Scars of Assimilation: Residential Schools and Cultural Genocide

The late 19th and early 20th centuries witnessed the most devastating policies aimed at cultural eradication. The Dawes Act of 1887 (General Allotment Act) sought to break up communal reservation lands into individual plots, further eroding traditional landholding systems and opening up "surplus" lands to non-Native settlement.

Even more insidious were the residential (or boarding) schools. Children, often as young as four or five, were forcibly removed from their families and communities and sent to institutions far from home. The infamous motto, "Kill the Indian, Save the Man," encapsulated their mission. In these schools, children were forbidden to speak their Ojibwemowin language, practice their spiritual traditions, or wear their traditional clothing. They endured harsh discipline, physical and emotional abuse, and often malnutrition. Generations of Ojibwe people carry the deep intergenerational trauma inflicted by these institutions, which severed family bonds and disrupted the transmission of culture and language. "They took our children, and with them, they tried to take our future," one survivor might recount, "but they could not take our spirit."

Resilience and Revival: The Fight for Sovereignty and Culture

Despite these systematic attempts at cultural annihilation, the Ojibwe spirit persevered. The mid-20th century saw a resurgence of Indigenous activism, spurred by the American Civil Rights Movement and a growing awareness of treaty obligations. The Red Power movement of the 1960s and 70s galvanized communities, demanding self-determination and the honoring of treaty rights.

A pivotal moment for the Ojibwe in the Great Lakes was the series of legal battles in the latter half of the 20th century to reaffirm their usufructuary rights – the reserved rights to hunt, fish, and gather on ceded lands. Landmark court decisions, such as those related to the Lac Courte Oreilles Band of Lake Superior Chippewa (LCO) in Wisconsin, upheld these treaty rights, often in the face of intense anti-Indian backlash from non-Native sportspersons. These legal victories were not just about fishing and hunting; they were about affirming sovereignty, restoring cultural practices, and asserting their inherent right to self-governance.

Today, Ojibwe communities across the Great Lakes are vibrant and dynamic. They are actively engaged in language revitalization programs, with immersion schools teaching Ojibwemowin to new generations. Cultural centers celebrate traditional arts, ceremonies, and storytelling. Economically, many Ojibwe nations have established successful enterprises, including casinos, resorts, and resource management initiatives, which fund essential community services like healthcare, education, and housing.

Environmental stewardship remains a core value. Ojibwe nations are often at the forefront of protecting the Great Lakes and surrounding ecosystems from pollution, climate change, and unsustainable resource extraction, embodying their ancient teaching that "the land is our mother, and we are her caretakers."

A Living History

The history of the Ojibwe in the Great Lakes region is a profound testament to human endurance. It is a story of a people who have navigated vast migrations, adapted to new technologies, survived epidemics and genocidal policies, and continuously fought for their inherent rights. From the ancient prophecies of the Seven Fires to the modern-day struggle for sovereignty and environmental justice, the Ojibwe continue to shape the Great Lakes region. Their voice, resilient and strong, remains an enduring heartbeat in the heart of Gichigami, reminding us that true history is not just about the past, but about the living present and the future yet to unfold.