Stolen Childhoods, Enduring Scars: The Unspoken Trauma of Native American Women in Boarding Schools

The image of an American schoolhouse typically evokes notions of learning, community, and the promise of a brighter future. But for generations of Native American children, particularly girls, these institutions represented something far darker: a systematic assault on their identity, culture, and spirit, designed to "kill the Indian, save the man." For over a century, federal Indian boarding schools, both on and off reservations, became instruments of forced assimilation, leaving an indelible legacy of trauma that continues to echo through Native communities today. While the experiences of all children in these schools were harrowing, Native American women bore a unique burden, facing specific forms of oppression that compounded their suffering and disrupted traditional roles for generations.

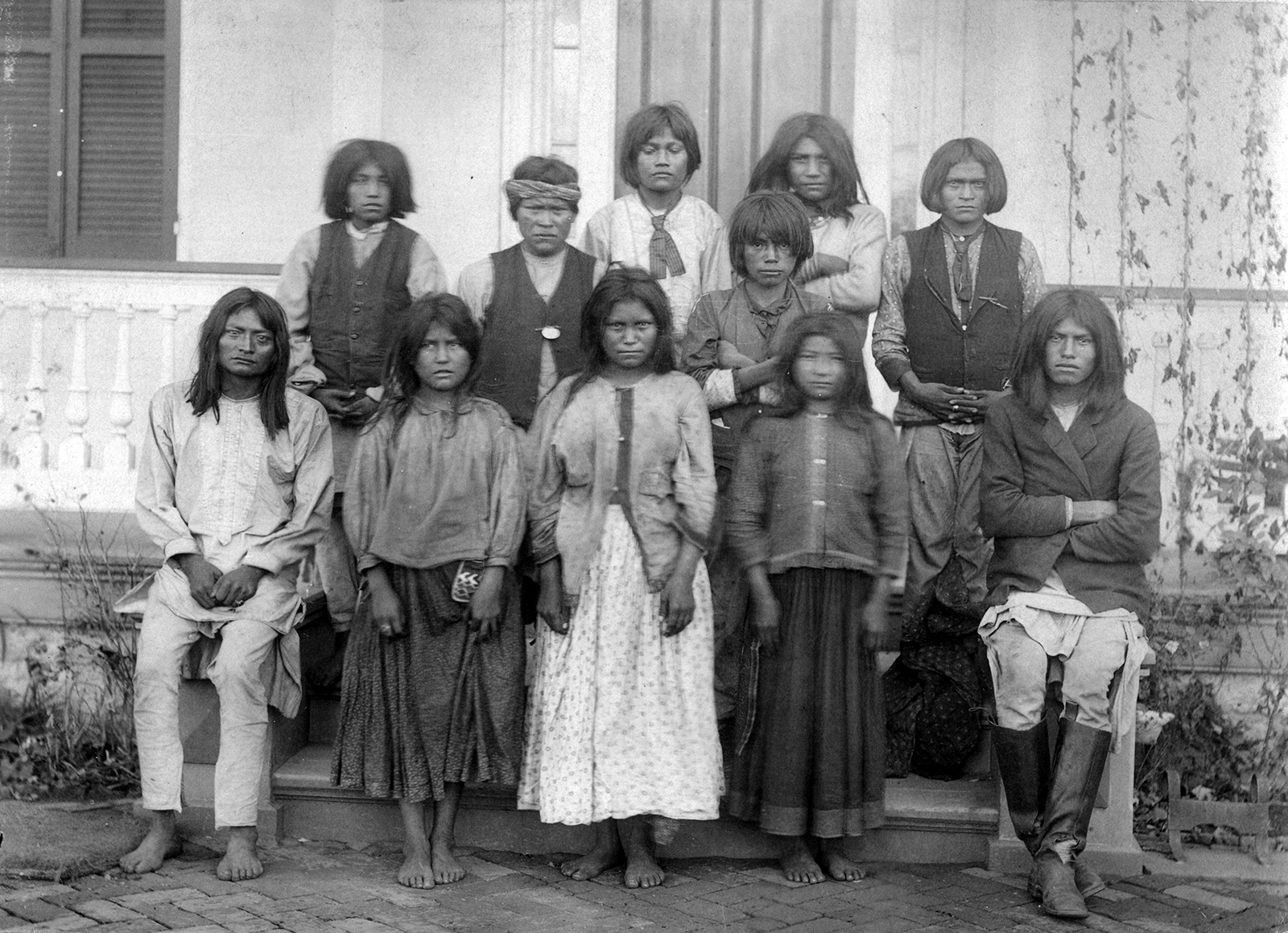

The policy of removing Native children from their families and sending them to boarding schools began in the late 19th century, fueled by a paternalistic belief that Indigenous cultures were inferior and an impediment to "progress." Richard Henry Pratt, founder of the infamous Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania, famously articulated the philosophy: "Kill the Indian, save the man." This ethos permeated the hundreds of schools that sprang up across the nation, funded by the U.S. government and often run by religious organizations. From the moment children arrived, usually transported hundreds or thousands of miles from their homes, the process of erasure began.

Girls, often as young as four or five, were immediately stripped of their traditional clothing, their long hair—a sacred symbol in many tribal cultures—was cut short, and their Indigenous names were replaced with English ones. Speaking their native languages was strictly forbidden, often enforced with harsh physical punishments like beatings, solitary confinement, or having their mouths washed out with soap. "They cut our hair, burned our clothes, and told us our language was evil," shares Eleanor Red Cloud, a fictional elder from the Lakota Nation, her voice etched with a pain that time cannot fully heal. "It was like they were trying to erase who we were, to make us forget our mothers, our grandmothers, everything that made us, us."

The curriculum for girls was starkly different from that of boys. While boys were taught trades like carpentry, farming, or blacksmithing, girls were primarily trained for domestic service. Their days were filled with laborious tasks: cooking, cleaning, laundry, sewing, and childcare for younger students. This vocational training was not about empowering them but about preparing them for subservient roles in white society, or to return to their communities as "civilized" homemakers who would instill Euro-American values in their families. They were taught to be maids, laundresses, or wives, stripped of their inherent worth as tribal knowledge keepers, spiritual leaders, or community builders—roles many women held in their traditional societies.

Beyond the grueling labor and cultural stripping, the schools were rife with abuse. Physical violence was commonplace, used as a disciplinary tool for minor infractions or perceived disobedience. Malnutrition and rampant disease, particularly tuberculosis, claimed countless lives due to overcrowded, unsanitary conditions and inadequate medical care. The U.S. Department of the Interior’s recent investigative report, "Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative Investigative Report," acknowledged that these schools were characterized by "systematic militarized and identity-alteration methodologies" and often resulted in "child abuse and neglect." The report further identified over 500 unmarked burial sites at boarding school locations, a grim testament to the thousands of children who never returned home.

However, it was the pervasive sexual abuse, particularly against girls, that inflicted some of the deepest and most enduring wounds. Vulnerable and isolated, far from the protection of their families and communities, many girls became targets for teachers, administrators, and even older students. The shame and secrecy surrounding these assaults, coupled with the institutions’ deliberate efforts to silence victims, meant that these crimes often went unpunished and unacknowledged for decades. The trauma of sexual violence compounded the cultural and emotional devastation, leaving survivors with profound psychological scars, including PTSD, depression, and a deep-seated mistrust of authority figures.

The long-term consequences for Native American women who survived these schools are profound and intergenerational. Many returned home to communities they barely recognized, struggling to communicate with their elders in languages they had been forced to abandon. They often found themselves alienated, caught between two worlds, belonging fully to neither. Having been denied proper parenting and affection, and subjected to harsh, authoritarian environments, many survivors struggled with their own roles as mothers and caregivers. "We didn’t know how to be mothers, because we were never mothered ourselves," says Mary Little Feather, a fictional generational survivor, echoing a sentiment shared by many. "We were taught to be quiet, to work, to survive, not to nurture or express love in the ways our ancestors did."

This disruption of traditional family structures and parenting styles led to cycles of intergenerational trauma. Children of boarding school survivors often experienced emotional detachment, difficulty forming healthy attachments, and a lack of cultural grounding that their parents, in turn, had been robbed of. The abuse and neglect suffered in the schools contributed to higher rates of substance abuse, mental health issues, and domestic violence within Native communities, as unresolved pain manifested in destructive ways. The resilience of Native women, historically the bedrock of their communities, was severely tested. Their traditional roles as cultural bearers, language speakers, and spiritual guides were systematically undermined, leading to a profound loss of ancestral knowledge and practices.

Despite the relentless assault on their identity, Native American women showed remarkable strength and resilience. Many secretly preserved their languages and traditions, whispering stories and songs to their children after lights out, or finding ways to practice their ceremonies away from the watchful eyes of school staff. Some ran away, enduring incredible hardships to return to their families. In the decades following the official closure of most federal boarding schools by the mid-20th century, survivors began to break the silence, sharing their painful testimonies and demanding accountability.

Today, there is a growing movement for truth, healing, and reconciliation. The U.S. Department of the Interior’s ongoing investigation into the federal Indian boarding school system is a crucial step towards acknowledging the scale of the atrocities committed. Advocates, many of them Native women, are leading efforts to locate burial sites, repatriate remains, and ensure that the stories of survivors are heard and remembered. Organizations like the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition (NABS) are working to address the lasting impacts of these schools, supporting survivors and their descendants through education, advocacy, and healing initiatives.

The experiences of Native American women in boarding schools represent a dark chapter in American history, one that speaks to the profound and lasting consequences of cultural genocide. Their stories are not merely historical footnotes; they are living testaments to the strength of the human spirit in the face of unimaginable cruelty, and a stark reminder of the importance of acknowledging historical injustices. As these truths continue to emerge, it is imperative that society listens, learns, and supports the ongoing journey of healing and reconciliation, ensuring that the voices of these resilient women are finally heard and honored. Only then can the scars of the past begin to mend, and the promise of a truly just future for Native nations be realized.