The Silent Chroniclers: Unveiling the Enduring Legacy of Native American Winter Counts

In the vast, sweeping landscapes of the North American Plains, where the wind whispers tales of ancient peoples and the buffalo once roamed in thundering herds, a unique and profound system of historical record-keeping flourished for centuries. Far from the written scripts of European civilizations, Native American tribes developed a sophisticated method of chronicling their past: the Winter Count. More than mere art, these pictorial calendars are invaluable historical documents, mnemonic devices, and vibrant testaments to the ingenuity and cultural depth of Indigenous peoples.

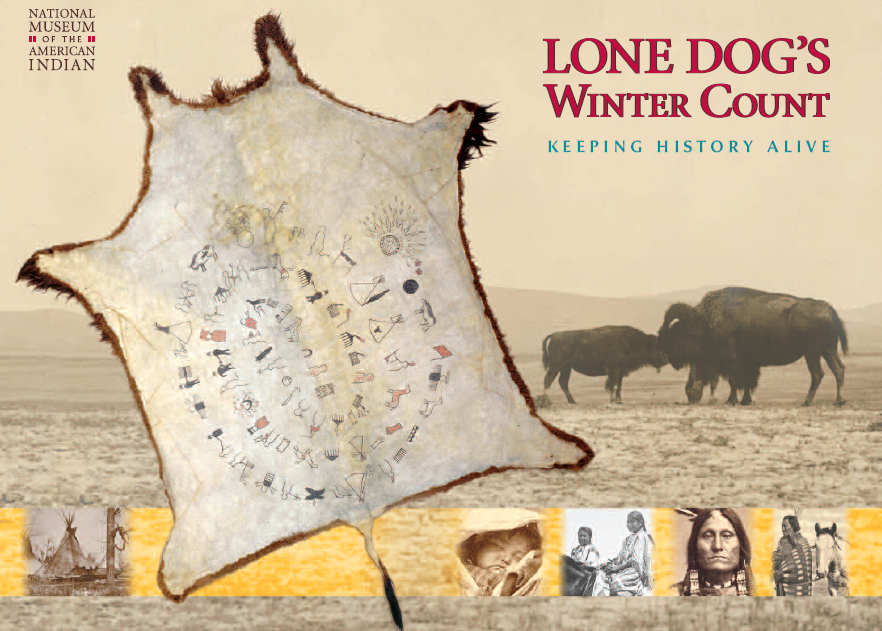

The Winter Count, known in Lakota as Waniyetu Wowapi, translates literally to "year count" or "winter record." It is an annual historical record, typically maintained by a designated tribal historian, that chronicles the most significant event of each year from one winter to the next. The passage of time was not measured by a fixed calendar but by the cycle of seasons, with winter marking the end of one year and the beginning of another. Each year was represented by a single, distinctive pictograph, chosen to encapsulate the most memorable occurrence – an event so impactful that it would define the entire year in the collective memory of the community.

These visual annals served as a vital repository of tribal knowledge, an Indigenous archive etched onto animal hides, cloth, or later, paper. Unlike the linear, text-based histories familiar to Western scholarship, Winter Counts are inherently circular or spiral, mirroring the cyclical nature of time and life as perceived by many Native American cultures. They begin with an inaugural event and expand outward or inward, each symbol building upon the last to form a continuous narrative of the tribe’s journey.

Historical Record-Keeping: A Tapestry of Time

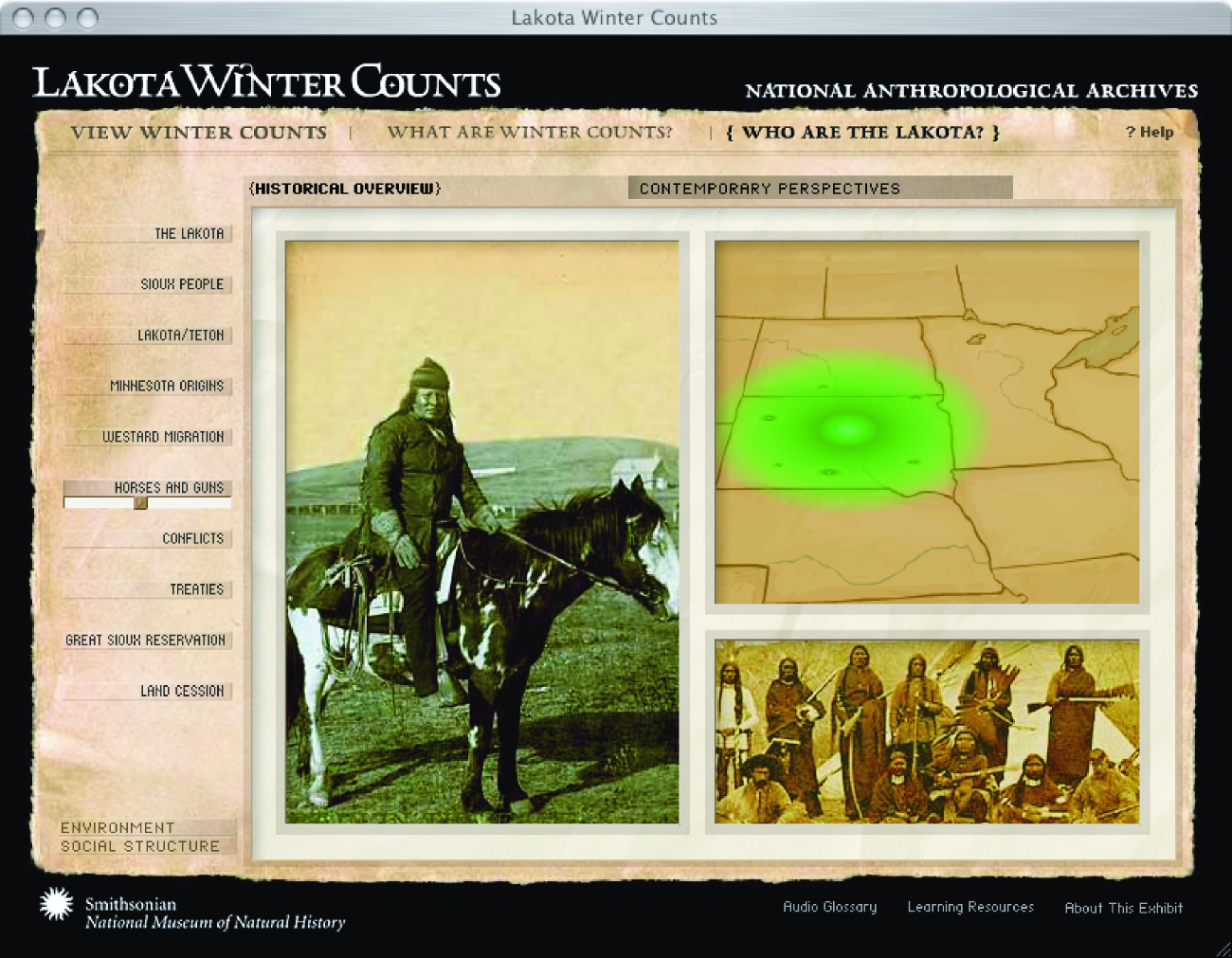

The historical depth captured by Winter Counts is astonishing. They document everything from major celestial events like meteor showers or solar eclipses to devastating epidemics, successful buffalo hunts, intertribal conflicts, treaties, significant ceremonies, and the deaths of prominent leaders. For example, the F.B. Mathers Lakota Winter Count, spanning from 1701 to 1902, records events like "Smallpox Year" (1795-96), "Many Buffalo" (1800-01), and "First Steamboat on Missouri" (1831-32). These entries are not just isolated facts; they are anchors for elaborate oral narratives, which were recounted by the Winter Count keeper, often a revered elder, during communal gatherings. The pictographs acted as prompts, triggering detailed stories that preserved the nuances of each historical moment.

Dr. Candace Greene, an ethnologist at the Smithsonian Institution, emphasizes the crucial role of these counts: "They are not just lists of events; they are mnemonic devices for oral history. The image is a shorthand for a much longer story that the keeper knew and would tell." This interplay between the visual and the oral is central to their function, making them dynamic rather than static records. The act of recounting the year’s events, prompted by the pictograph, reinforced tribal identity, educated younger generations, and maintained a collective memory that spanned generations.

The accuracy and detail within some Winter Counts are remarkable. For instance, the Kiowa Winter Counts, particularly those kept by Anko and Dohasan, provide an unbroken record from the late 18th century well into the 20th century, offering invaluable insights into Kiowa migrations, interactions with other tribes, and adaptation to the changing landscape during the era of Euro-American expansion. These records often provide an Indigenous counter-narrative to colonial accounts, offering perspectives and details often omitted or misunderstood by non-Native observers. They stand as powerful evidence of a sophisticated historical consciousness existing independently of written language.

Pictorial Calendars: Marking the Rhythms of Life

Beyond their role as historical annals, Winter Counts functioned as sophisticated pictorial calendars, providing a chronological framework for understanding the passage of time and the sequence of events. Each pictograph represents a specific year, from one winter’s first snow to the next. This annual cycle, defined by the most severe season, reflects the deep connection between Native American cultures and the natural world.

The choice of event for each year was often a communal decision, reflecting what was most memorable or impactful for the entire group. It could be something as grand as "The Year the Stars Fell" (a reference to the Leonid meteor shower of November 1833, widely documented across many Plains tribes’ Winter Counts) or as personal as "Year of the White Buffalo Calf" – an event of profound spiritual significance. The visual language employed was often symbolic and sometimes highly stylized, requiring an understanding of tribal iconography and cultural context to fully interpret. A drawing of a stick figure with a bleeding mouth might signify a smallpox epidemic, while a stylized buffalo with an arrow through it could denote a particularly successful hunt or a time of abundance.

The interpretation of Winter Counts is not always straightforward for outsiders. Ethnohistorians and anthropologists often rely on the oral traditions passed down with the counts, as well as comparative analysis across different tribal records, to decipher their meanings. The same event might be depicted differently by different keepers, or a similar pictograph might represent distinct events in different tribal contexts. This complexity underscores their authenticity as indigenous cultural products, deeply rooted in specific worldviews and artistic traditions.

Artistry, Keepers, and Enduring Significance

The creation of a Winter Count was a significant undertaking, requiring not only a prodigious memory but also artistic skill. The materials used varied: early counts were typically rendered on buffalo hides, carefully tanned and prepared to last for generations. The images were painted with natural pigments derived from plants and minerals, applied with bone or wood tools. As contact with Euro-Americans increased, canvas and paper became more common mediums, and pencils or inks were sometimes used.

The role of the Winter Count keeper was one of immense prestige and responsibility. They were the living libraries of their people, entrusted with the sacred duty of preserving and transmitting history. Their knowledge was not merely factual but deeply interwoven with the spiritual and cultural fabric of the tribe. The creation and maintenance of a Winter Count was a communal act, reflecting the shared experiences and memories of the entire group.

Today, Winter Counts are recognized as invaluable ethnographic and historical resources. They provide unique perspectives on pre-contact Native American life, the devastating impact of colonization, and the resilience of Indigenous cultures. They offer critical data on climate, demographics, intertribal relations, and cultural practices that are often absent from Euro-American historical records. For many Native American communities, they remain powerful symbols of identity, continuity, and cultural sovereignty. Museums and archives around the world house these precious documents, but efforts are increasingly being made to repatriate them or to ensure that tribal communities have direct access to and control over their own historical narratives.

In a world increasingly dominated by digital information, the silent chronicles of the Winter Counts stand as a powerful reminder of the enduring human need to record, remember, and transmit history. They are not merely records of the past but living connections to ancestral wisdom, offering profound insights into the rhythms of life on the Plains and the incredible resilience of the peoples who called them home. Their pictographs, etched across the centuries, continue to speak, whispering tales of triumph and tragedy, adaptation and survival, for those who are willing to listen and learn.