Native American Voting Rights: Historical Barriers and Modern Political Participation

The struggle for Native American voting rights is a profound and often overlooked chapter in the story of American democracy. While the concept of self-governance and tribal sovereignty predates the United States itself, the Indigenous peoples of this land have faced centuries of systemic disenfranchisement, only truly securing their right to vote in all states decades after other minority groups. This journey from exclusion to increasing political participation is marked by persistent historical barriers, ongoing modern challenges, and a growing, vital influence on the nation’s political landscape.

The Long Road to Citizenship and Suffrage: Historical Barriers

For the Indigenous inhabitants of what is now the United States, the right to vote was not a birthright, but a hard-won battle. Initially, Native Americans were not considered citizens of the United States. The prevailing view was that they belonged to sovereign nations, and thus, were not subject to U.S. laws, nor were they afforded U.S. rights. This legal ambiguity, often used to deny them civil liberties, meant they were simultaneously subjected to federal and state policies designed to dispossess them of land and culture, while being excluded from the democratic process that shaped these very policies.

One of the earliest attempts to integrate, or rather assimilate, Native Americans into American society was the Dawes Act of 1887. This act broke up communal tribal lands into individual allotments and offered citizenship to those who accepted allotments and severed ties with their tribes. However, this was a Trojan horse: designed to dismantle tribal structures and seize surplus land, it did not genuinely empower Native Americans politically, as state laws often still denied them the franchise.

The pivotal moment for Native American citizenship came with the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924. Signed into law by President Calvin Coolidge, this act declared all non-citizen Native Americans born within the territorial limits of the United States to be citizens. It was a landmark piece of legislation, ostensibly granting Native Americans the same rights as other Americans, including the right to vote. However, the reality was far more complex. The Act did not universally guarantee suffrage, as states retained the power to define voter qualifications. Many states, particularly in the West, exploited this loophole, using a variety of discriminatory practices to continue denying Native Americans the right to cast a ballot.

For decades after 1924, states like Arizona and New Mexico explicitly barred Native Americans from voting, often citing that those living on reservations were "wards of the government" and therefore not subject to state jurisdiction, or that they were "not taxed." This legal sophistry was exposed in cases like Harrison v. Laveen (1948), where the Arizona Supreme Court finally struck down the state’s prohibition on Native American voting, stating, "To deny the right to vote, where all other requirements are met, is to deny the equal protection of the law." New Mexico followed suit in 1953.

Beyond legal barriers, Native Americans faced the same types of disenfranchisement tactics used against African Americans in the Jim Crow South: literacy tests, poll taxes, intimidation, and violence. Polling places were often located far from reservations, requiring arduous journeys. Language barriers were also a significant obstacle, as election materials and officials rarely provided assistance in Indigenous languages. The irony was not lost on many: Native American soldiers, like the Navajo Code Talkers, served with distinction in World War II, fighting for a nation that still denied them fundamental rights upon their return home.

The Voting Rights Act (VRA) of 1965 was a watershed moment for civil rights, yet its initial scope did not fully address the unique challenges faced by Native Americans. While it prohibited racial discrimination in voting, it was primarily focused on African American disenfranchisement in the South. It wasn’t until the VRA Amendments of 1975 that significant protections for language minority groups, including Native Americans, were enshrined in federal law. These amendments mandated bilingual ballots and voting assistance in areas with significant language minority populations, finally beginning to dismantle some of the more overt barriers to access.

The Modern Landscape: Persistent Challenges

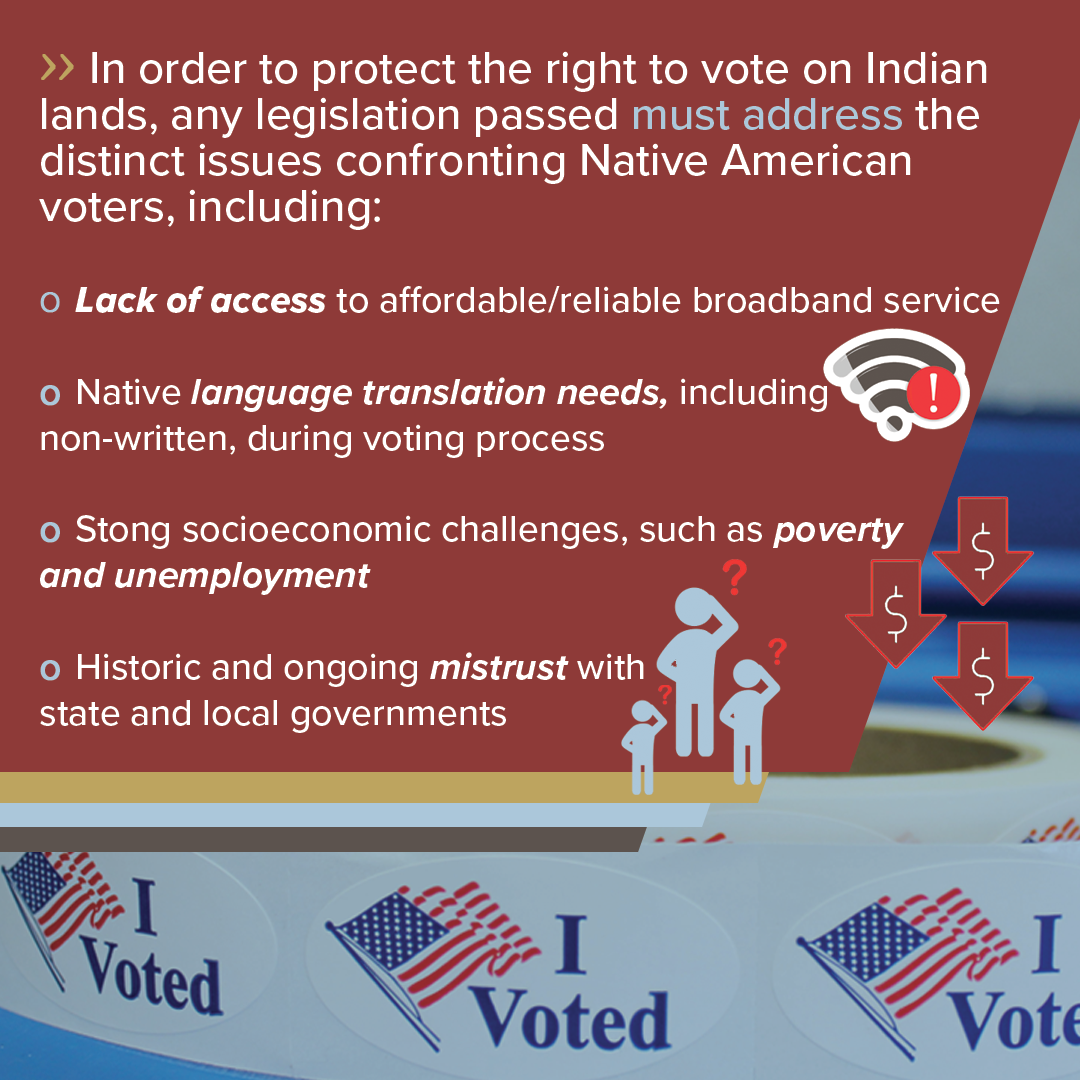

Despite the legal victories of the 20th century, Native Americans continue to face a unique set of challenges that impede their full political participation. These barriers are often rooted in the historical legacy of colonialism, geographic isolation, and the complex federal-tribal relationship.

One of the most significant challenges is geographic isolation and inadequate infrastructure. Many reservations are located in remote areas, far from urban centers. This often means a lack of reliable mail service, which is critical for absentee voting, and a scarcity of polling places within tribal lands. Voters may have to travel dozens or even hundreds of miles to cast a ballot, a burden amplified by limited access to transportation, particularly for elders or those with disabilities. A 2020 study by the Native American Rights Fund (NARF) found that Native Americans in some areas had to travel ten times farther to reach a polling place than their non-Native counterparts.

Voter ID laws present another significant hurdle. Many Native Americans living on reservations do not have standard residential street addresses; their homes may be identified by descriptive locations or P.O. boxes. This can make it difficult to obtain state-issued identification cards that align with typical voter ID requirements. While tribal IDs are valid forms of identification, they are not universally accepted at polling places, leading to confusion and potential disenfranchisement.

Gerrymandering and redistricting efforts have historically diluted Native American voting power. By drawing district lines that split tribal communities or merge them with overwhelmingly non-Native populations, their ability to elect candidates of their choice is significantly diminished. This strategic weakening of their collective vote undermines their representation at local, state, and federal levels.

Language access remains an issue, even with the 1975 VRA amendments. While bilingual materials are mandated in some areas, the reality on the ground can be different. A lack of trained, culturally competent poll workers who speak Indigenous languages, or insufficient distribution of translated materials, can still prevent voters from understanding the ballot or the voting process.

Furthermore, misinformation and disinformation campaigns, often targeting remote communities through social media or word-of-mouth, can suppress turnout by sowing confusion about voter registration deadlines, polling locations, or eligibility requirements. The lack of robust federal funding for election administration on tribal lands also contributes to these issues, leaving many tribal governments to shoulder the burden of voter outreach and education with limited resources.

Rising Power: Modern Political Participation and Impact

Despite these formidable obstacles, Native American political participation has seen a significant surge in recent decades, driven by robust grassroots organizing, increased voter education, and a growing recognition of their collective power. This rising influence is transforming the political landscape, particularly in states with large Indigenous populations.

Organizations like Native Vote, a project of the National Congress of American Indians (NCAI), have been instrumental in leading voter registration drives, educating communities on election procedures, and advocating for policies that protect Native American voting rights. Their efforts, combined with those of tribal governments and local activists, have led to increased voter turnout and engagement.

The impact of the Native American vote has become undeniable in recent elections. In states like Arizona and Nevada, where Indigenous populations are significant, the Native American vote has been credited as a decisive factor in close statewide and federal races. For example, in the 2020 presidential election, the high turnout among the Navajo Nation and other tribal communities in Arizona was widely recognized as critical to the state’s outcome. This growing political clout is forcing candidates and parties to pay closer attention to tribal issues and engage more directly with Indigenous communities.

This increased participation has also translated into a surge of Native American candidates running for and winning public office. The election of Deb Haaland (Laguna Pueblo) as the first Native American Cabinet Secretary (Secretary of the Interior) in 2021 was a historic milestone, signifying unprecedented representation at the highest levels of government. Similarly, Sharice Davids (Ho-Chunk Nation) became one of the first two Native American women elected to Congress in 2018, and has since been re-elected. Beyond Congress, Native Americans are increasingly serving in state legislatures, on tribal councils, and in local government positions, bringing unique perspectives and a deep understanding of Indigenous issues to policy-making.

Legal challenges continue to be a vital tool in protecting and expanding Native American voting rights. Advocacy groups frequently litigate against discriminatory voter ID laws, polling place closures, and restrictive registration requirements. Many of these lawsuits have resulted in favorable rulings, forcing states to provide more accessible voting options, such as satellite polling places on reservations or greater acceptance of tribal identification.

The focus on youth engagement is also growing, ensuring that the next generation understands the importance of their vote and continues the fight for full political equity. Educational initiatives within tribal schools and communities are fostering civic responsibility and encouraging young Native Americans to become active participants in the democratic process.

Conclusion

The journey of Native American voting rights reflects a profound paradox: the original inhabitants of this land were among the last to fully secure their place in its democratic processes. From the systemic exclusions of the past, rooted in legal ambiguity and racial discrimination, to the modern challenges of geographic isolation, voter ID laws, and gerrymandering, the path has been arduous. Yet, the story is also one of immense resilience, persistent advocacy, and growing empowerment.

Today, Native Americans are not merely seeking the right to vote; they are exercising it with increasing effectiveness, electing their own representatives, influencing critical elections, and advocating for policies that reflect their values and needs. Their participation is not just about individual suffrage; it is intrinsically linked to tribal sovereignty and self-determination, strengthening the voice of Indigenous nations in the broader American political dialogue. The struggle continues, demanding ongoing vigilance and commitment, but the rising tide of Native American political engagement is a powerful testament to their enduring spirit and an essential force for a more inclusive and representative democracy.