Native American Tribal Garden Designs: Ancient Wisdom for Modern Cultivation

For millennia, the indigenous peoples of North America cultivated sophisticated agricultural systems that sustained thriving communities, nourished diverse ecosystems, and embodied a profound spiritual connection to the land. Far from haphazard plots, Native American tribal garden designs were intricate matrices of traditional planting methods and thoughtful layouts, showcasing an ecological intelligence that predated modern permaculture by centuries. These designs were not merely about growing food; they were holistic expressions of culture, ceremony, and survival, reflecting a deep understanding of natural processes and a philosophy of reciprocity with the Earth.

The core principle underpinning Native American horticulture was a symbiotic relationship with nature, viewing plants not as resources to be exploited but as relatives to be nurtured. This worldview informed every aspect of their gardening, from site selection to harvesting. Their methods were inherently sustainable, designed to enhance soil fertility, conserve water, deter pests naturally, and maintain biodiversity, ensuring bounty for not just one season but for generations.

The Ingenuity of Traditional Planting Methods

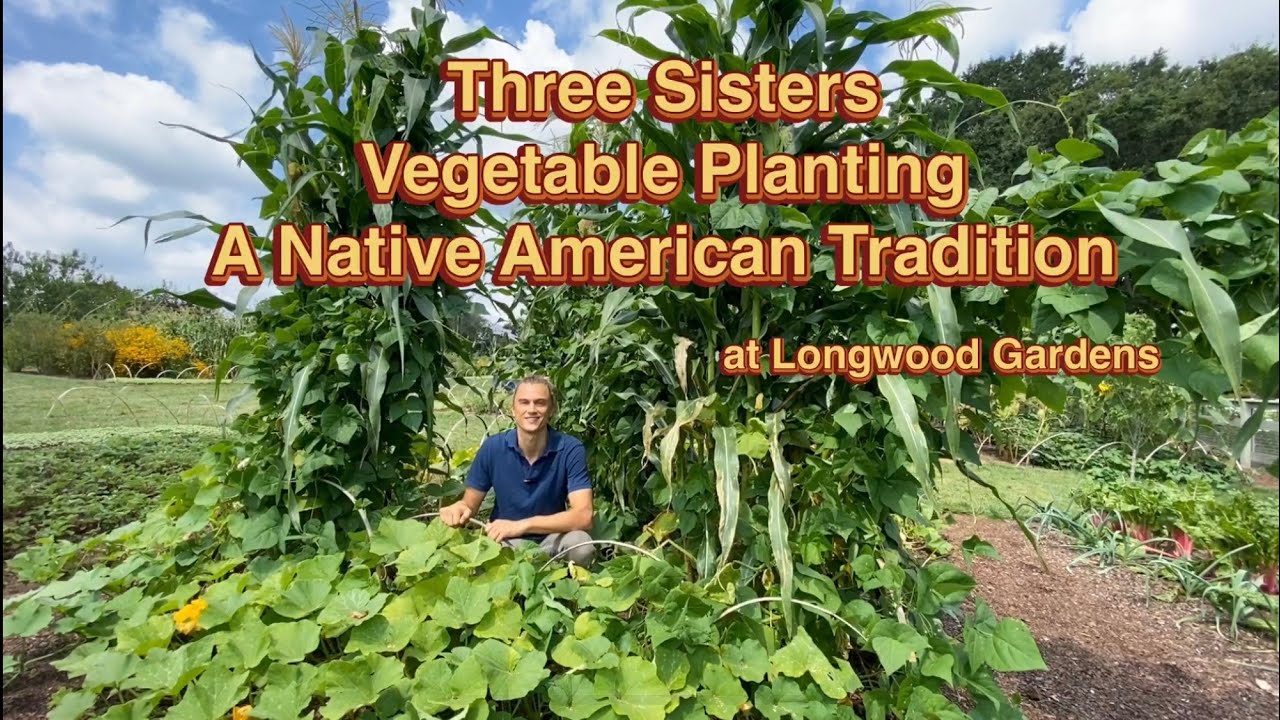

Perhaps the most iconic and widely recognized Native American planting method is the Three Sisters garden: corn, beans, and squash grown together. This brilliant polyculture system exemplifies companion planting at its finest, creating a miniature ecosystem where each plant supports the others. The corn provides a natural trellis for the climbing beans. The beans, through nitrogen-fixing bacteria in their root nodules, enrich the soil, providing essential nutrients for the heavy-feeding corn and squash. The broad leaves of the squash plants spread across the ground, shading the soil, conserving moisture, and suppressing weeds. They also deter pests with their prickly stems. This ancient technique, practiced by tribes from the Iroquois to the Cherokee, is a masterclass in bio-integration. "The Three Sisters are more than just crops," explains Robin Wall Kimmerer, a botanist and member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, "they are teachers. They teach us about reciprocity, about mutual support, and about the gifts of the earth."

Beyond the Three Sisters, indigenous gardeners employed a range of other companion planting guilds. Sunflowers were often planted at the edges of gardens to provide shade, attract pollinators, and act as a windbreak. Marigolds and other aromatic plants were used to repel insects. Certain medicinal herbs were interspersed with food crops, serving dual purposes of health and pest management. This intricate web of plant relationships minimized the need for external inputs, fostering a resilient and productive environment.

Water management, particularly in arid regions, was another area of profound innovation. The Zuni and Hopi peoples of the American Southwest, for instance, developed sophisticated waffle gardens. These involve creating a grid of raised earth walls around small planting beds, forming a "waffle" pattern. Each square depression captures and holds precious rainwater, directing it directly to the plant roots and minimizing evaporation. This technique, combined with selective planting of drought-tolerant crops like specific varieties of corn, beans, and melons, allowed for successful agriculture in incredibly challenging environments. Similarly, other tribes utilized terracing on hillsides and intricate systems of check dams and diversion channels to harness and distribute water efficiently, preventing erosion while nourishing their crops.

Soil fertility was maintained through natural processes. Instead of synthetic fertilizers, Native American gardeners relied on crop rotation, the incorporation of organic matter such as wood ash, composted plant material, and even fish scraps, particularly in coastal regions. Mounding was a common practice, creating raised beds that improved drainage and allowed the soil to warm up faster in spring. These mounds were often renewed annually, incorporating fresh organic matter. The focus was always on nurturing the soil, recognizing it as the foundation of all life.

Furthermore, seed saving and selective breeding were paramount. Generations of careful observation and selection led to the development of thousands of indigenous crop varieties, each adapted to specific microclimates, soil types, and cultural preferences. This dedication to genetic diversity ensured resilience against disease, pests, and changing environmental conditions, a stark contrast to the monoculture practices prevalent in modern industrial agriculture.

Layouts Reflecting Cosmic Order and Practicality

Native American garden designs were not merely functional; they were often imbued with cultural and spiritual significance, reflecting a holistic worldview that saw humanity as an integral part of the natural world. While specific layouts varied widely among tribes based on geography, climate, and cultural beliefs, common themes emerged.

Many designs incorporated circular or spiral patterns, echoing the cycles of nature and the cosmos. The circle is a sacred shape in many indigenous cultures, representing unity, infinity, and the interconnectedness of all things. These circular gardens could optimize sun exposure, facilitate water distribution, and create microclimates within the planting area. For example, a central mound might host corn, surrounded by rings of beans, squash, and other complementary plants, forming a vibrant, living mandala.

In larger agricultural fields, tribes often employed field patterns that optimized labor and resource use. The Iroquois, for instance, cultivated extensive fields of corn, beans, and squash around their longhouses, often in strips or blocks that allowed for efficient planting, tending, and harvesting by communal work groups. These fields were not isolated but were often integrated into the broader landscape, with nearby forests providing wild edibles, medicinal plants, and hunting grounds.

The concept of an "edible landscape" was inherent in Native American design. Gardens weren’t confined to a single plot but often extended into the surrounding environment. Fruit trees, berry bushes, nut trees, and medicinal plants were often incorporated directly into the garden layout or managed in adjacent areas, blurring the lines between cultivated and wild. This approach maximized biodiversity and provided a wider range of sustenance and resources.

Crucially, site selection was never arbitrary. Indigenous gardeners possessed an intimate knowledge of their local topography, sun exposure, prevailing winds, and water sources. They would choose locations that offered natural protection, optimal drainage, and access to water, often observing the growth of wild plants as indicators of soil health and suitability. This deep observational skill allowed them to work with the land rather than against it.

Cultural Significance and Enduring Wisdom

The practice of gardening was deeply intertwined with Native American cultural identity, ceremony, and community structure. Planting and harvesting were often accompanied by elaborate rituals, songs, and prayers of gratitude to the Earth and the plant spirits. These ceremonies reinforced the spiritual connection to the land and the crops, emphasizing humility and thankfulness for nature’s bounty.

Gardens were also central to community building and knowledge transmission. Children learned traditional gardening methods by working alongside elders, absorbing not just the techniques but also the underlying philosophy of respect and reciprocity. The shared labor of planting, tending, and harvesting fostered strong community bonds and ensured collective food security.

Today, as modern societies grapple with issues of food insecurity, climate change, and environmental degradation, the ancient wisdom embedded in Native American tribal garden designs offers invaluable lessons. Contemporary indigenous communities are leading a powerful resurgence of these traditional practices, not just to reclaim cultural heritage but also to provide sustainable, healthy food for their people. Projects like the Native American Food Sovereignty Alliance and numerous tribal garden initiatives across the continent are demonstrating the enduring relevance of these methods.

"Our ancestors gardened in a way that truly sustained the land and people," says Clayton Brascoupe, a Mohawk seed keeper and director of the Traditional Native American Farmers Association. "We are bringing that knowledge back to help heal our communities and the Earth."

In essence, Native American tribal garden designs represent a sophisticated and holistic approach to agriculture that prioritizes ecological balance, biodiversity, and community well-being. They remind us that true sustenance comes not from dominating nature, but from understanding and honoring its intricate systems, cultivating a relationship of mutual respect and reciprocity that yields not only food but also wisdom, culture, and resilience for generations to come. Their ancient gardens were, and remain, living testaments to an enduring connection with the Earth, offering a path forward for a more sustainable and harmonious future.