Native American Tribal Fishing Techniques: Traditional Methods from Coast to Coast

From the thunderous rivers of the Pacific Northwest to the serene estuaries of the Southeast, and across the vast network of lakes and streams that crisscross the North American continent, Native American tribes have for millennia developed and refined an astonishing array of fishing techniques. These methods were not merely means of sustenance; they were interwoven with cultural identity, spiritual beliefs, and an profound understanding of ecological balance. Far from primitive, these traditional approaches demonstrate sophisticated engineering, deep biological knowledge, and a commitment to sustainability that offers invaluable lessons even today.

The story of Native American fishing is a testament to human ingenuity and adaptability, shaped by the diverse aquatic environments tribes inhabited. It is a narrative of profound respect for the natural world, where every catch was a gift, and every technique was a dialogue with the waters and the creatures within them.

The Sacred Salmon of the Pacific Northwest

Nowhere is the cultural and dietary significance of fish more apparent than among the tribes of the Pacific Northwest. For nations like the Nez Perce, Yakama, Lummi, Haida, and Tlingit, salmon was not just food; it was life itself – a sacred gift that returned annually, fueling their societies and spiritual practices. The Columbia and Fraser River systems, teeming with salmon, were the lifeblood of these communities.

Their fishing techniques were meticulously adapted to the salmon’s powerful upstream migrations. Fish weirs, complex structures of interwoven branches and stakes, were expertly constructed to funnel migrating salmon into holding pens or narrow channels where they could be easily harvested. These weirs, sometimes spanning entire rivers, required significant communal effort and demonstrated a deep understanding of hydrodynamics and fish behavior. "The salmon came to us, and we were there to meet them," an elder might say, reflecting the reciprocal relationship.

Dip nets were another iconic tool, particularly effective from platforms built over rapids or waterfalls where salmon would pause or leap. Fishermen, often standing precariously on scaffolds, would skillfully scoop individual salmon from the churning waters. The design of these nets, often with long handles and wide mouths, allowed for precise, selective harvesting. For tribes like the Haida and Tlingit, whose territories included rich coastal waters, trolling with hooks carved from bone or shell was common, as were intricate herring rakes – long poles studded with sharp points used to stun or impale schools of herring.

The First Salmon Ceremony, a widespread ritual, underscored the reverence for the fish. The first salmon caught each season was treated with immense respect, its flesh shared communally, and its bones returned to the river, ensuring the fish’s spiritual return and the continuity of the cycle. This practice embodied a core principle of sustainability: take only what is needed, and honor the source.

Ice, Rivers, and Lakes: The Great Lakes and Northeast

Moving eastward, the tribes of the Great Lakes and Northeast, including the Ojibwe (Anishinaabe), Iroquois, and Wampanoag, adapted their fishing methods to vast freshwater systems and harsh seasonal changes. Their techniques were as varied as the species they sought: walleye, lake trout, sturgeon, pike, and eels.

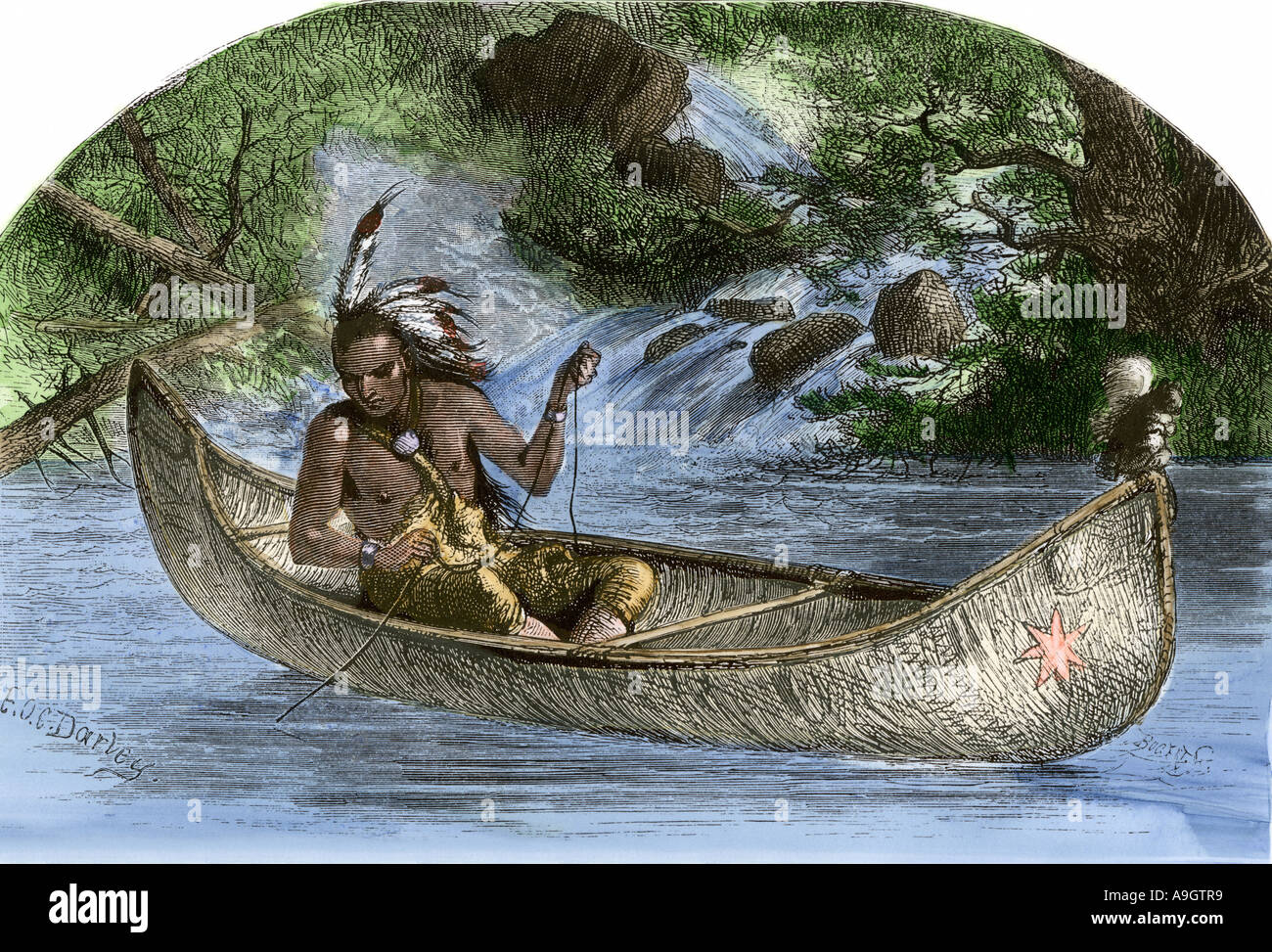

Spearfishing was a prominent technique, whether from canoes at night using torches to lure fish to the surface, or through the ice during the long winters. Ice fishing involved cutting holes in the thick ice and using lures to attract fish, then spearing them with multi-pronged spears. This required immense patience and knowledge of fish habits under frozen conditions.

Nets woven from plant fibers like nettle, basswood, or milkweed were common. These nets, often weighted with stones and buoyed with wood or gourds, could be set in rivers or lakes, sometimes spanning large areas. The sophisticated craftsmanship involved in creating these durable and effective nets speaks volumes about their textile skills.

Fish weirs were also extensively used in rivers and coastal estuaries to trap migrating fish like alewives and eels. The Wampanoag, for instance, constructed elaborate stone weirs in tidal rivers to capture fish as the tide receded. These structures, some of which are still visible today, represent enduring monuments to their ecological engineering. "The river gives us what we need, if we know how to ask," a Wampanoag elder might have observed, highlighting the careful observation and reciprocity involved.

Coastal Estuaries and Inland Waters: The Southeast

In the warm, often swampy, and water-rich environments of the Southeast, tribes like the Seminole, Miccosukee, Cherokee, and Creek developed methods suited to slow-moving rivers, lakes, and extensive coastal estuaries. Here, species like catfish, bass, gar, and mullet were staples.

Cast nets, skillfully woven and weighted, were used to ensnare schools of fish in open waters or shallow areas. The art of throwing a cast net to achieve a wide, perfect circle requires significant practice and precision. Trotlines, long lines with multiple baited hooks set across a river or lake, were efficient for catching bottom feeders like catfish.

A fascinating and highly specialized technique involved the use of natural plant poisons. Tribes would carefully select plants like the root of the "devil’s shoestring" (a type of Tephrosia) or various species of Lonchocarpus. When crushed and introduced into a confined body of water, these plants released compounds that temporarily stunned fish, causing them to float to the surface where they could be easily collected. Crucially, these compounds were not toxic to humans and dissipated quickly, ensuring the water remained safe and the ecosystem unharmed. This method demonstrates an intimate knowledge of botany and its application for sustainable harvesting.

Spearfishing and bow and arrow fishing were also practiced, particularly for larger, slower-moving fish like gar. The shallow, clear waters of many southeastern rivers provided ideal conditions for these direct methods.

Arid Lands, Ingenious Solutions: The Southwest and Great Basin

While fishing was not as central to the diet of many Southwest and Great Basin tribes as it was for coastal communities, ingenious methods were still employed in a land where water was a precious commodity. Tribes like the Hopi, Zuni, Paiute, and Shoshone found ways to harvest fish from seasonal rivers, springs, and even temporary pools.

Basket traps were common, set in streams or along the edges of ponds to capture small native fish and minnows. The Paiute, known for their skill in basketry, would weave intricate traps that were highly effective. In some areas, similar to the Southeast, plant-based stunning agents were used. The saponins from yucca root, when pounded and mixed in water, could temporarily disorient fish, making them easier to catch by hand or net in small, isolated pools.

The emphasis in these regions was on maximizing every available resource, a testament to their adaptability in challenging environments. Fishing was often an opportunistic activity, complementing hunting and gathering.

Rivers as Lifelines: The Plains

On the vast Great Plains, buffalo hunting often overshadowed other food procurement methods, but the major rivers like the Missouri, Platte, and Arkansas were vital sources of fish for tribes such as the Lakota, Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara. While not their primary food source, fish provided crucial dietary diversity, especially during certain seasons or when buffalo were scarce.

Weirs and nets were employed in the rivers, particularly during spawning runs. Spearing and hook and line fishing with hooks made from bone or antler were also common. The Mandan and Hidatsa, who lived in semi-permanent villages along the Missouri River, cultivated gardens and supplemented their diet with fish, using earth lodge settlements as bases for their riverine activities. Their approach to fishing, like their other subsistence activities, was integrated into a holistic understanding of their environment.

The Enduring Legacy: Sustainability and Sovereignty

Across this vast mosaic of landscapes and cultures, several common threads emerge in Native American tribal fishing techniques. Foremost is an unparalleled ecological knowledge. Tribes understood fish migration patterns, spawning habits, water currents, and the interconnectedness of their ecosystems with a precision that modern science is only now fully appreciating. This knowledge was passed down through generations, ensuring the continuity of both the resource and the culture.

Another critical element was sustainability. Traditional methods were rarely extractive in a way that depleted populations. Weirs allowed for selective harvesting, First Salmon ceremonies reinforced conservation, and plant-based stunning methods minimized harm to the environment. "We are stewards of the land and water, not owners," is a common sentiment expressed by tribal elders, encapsulating this philosophy.

Today, these traditional techniques and the principles behind them continue to hold immense relevance. Many tribes are actively reviving ancestral fishing practices, not just for cultural preservation but also for their inherent sustainability and efficiency. However, this legacy faces profound challenges. Dams have decimated salmon runs, pollution threatens water quality, and overfishing by commercial entities has strained fish populations.

The fight for treaty fishing rights is a continuous battle, asserting tribal sovereignty and the right to practice traditional ways. These rights, often guaranteed by historical treaties, are crucial for tribes to manage their own resources and maintain their cultural heritage. The re-establishment of traditional fishing practices is not just about catching fish; it’s about reconnecting with a profound spiritual relationship to the land and water, fostering community, and ensuring food security.

In essence, Native American tribal fishing techniques represent far more than simple methods of catching food. They are intricate systems of knowledge, belief, and practice that embody a deep respect for the natural world and a profound understanding of ecological balance. From the sophisticated weirs of the Northwest to the ingenious plant poisons of the Southeast, these traditions offer a powerful blueprint for sustainable living and a testament to the enduring wisdom of indigenous peoples in their timeless dialogue with the waters of North America. Their legacy continues to inspire, reminding us of the intricate beauty and profound intelligence embedded in living in harmony with the natural world.