Guardians of the Earth: Unpacking Native American Perspectives on Land Ownership

The very ground beneath our feet tells a different story depending on who is listening. For centuries, Western thought has largely viewed land as a commodity—a resource to be owned, bought, sold, and exploited for profit. This perspective, deeply ingrained in legal systems and economic structures, stands in stark contrast to the profound and multifaceted understanding of land that has permeated Native American cultures for millennia. To truly grasp the essence of Indigenous relationships with the earth is to embark on a journey that transcends mere property deeds, delving into realms of spirituality, community, and an enduring sense of reciprocal responsibility.

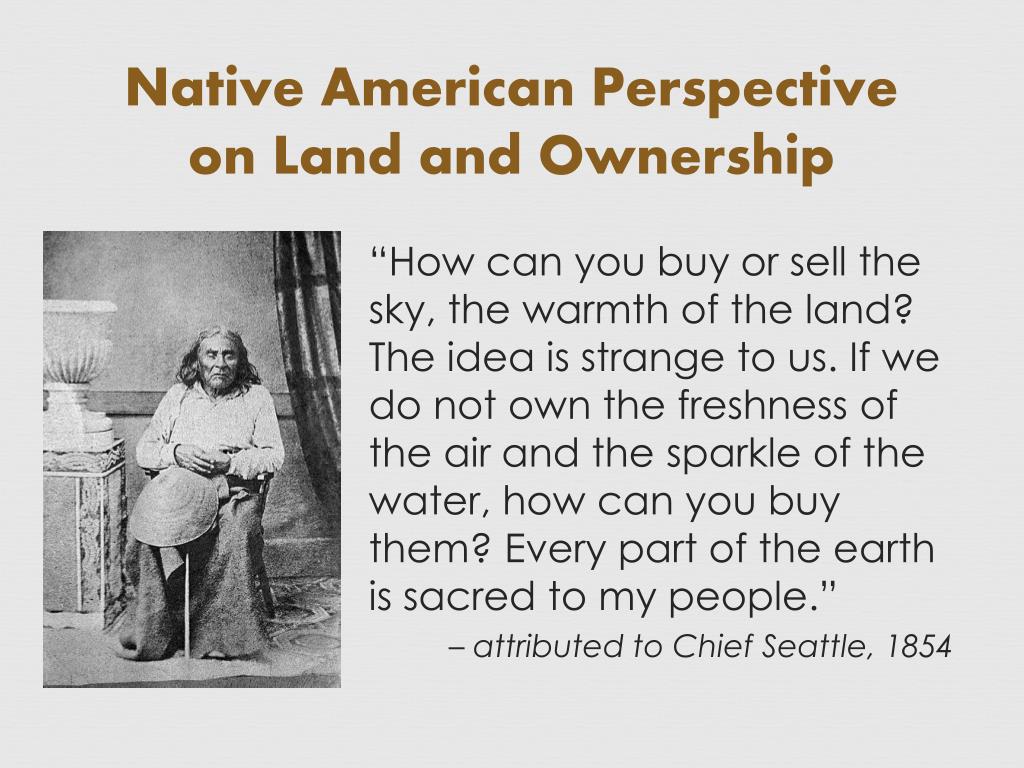

At the heart of Native American land ethics lies the concept of stewardship, not ownership. For most Indigenous nations, the idea of "owning" land was as absurd as claiming ownership of the air or the sky. Land was not an inert object; it was a living entity, a sacred relative, the source of all life. This perspective fostered a relationship of profound respect, humility, and gratitude. People belonged to the land, not the other way around. As Oren Lyons, Faithkeeper of the Onondaga Nation, eloquently states, "We are a part of the earth, not separate from it. Our history is recorded in the land, and our future depends on how we care for it."

This worldview manifested in distinct patterns of land use and governance. While specific territories were recognized and defended by various tribes, these boundaries often reflected areas of shared resource management, hunting grounds, and spiritual sites rather than exclusive private property. Rights to land were often usufructuary – the right to use and benefit from the land – held communally by the tribe or clan, ensuring that resources were managed sustainably for the benefit of current and future generations. Decisions regarding land were made through consensus, considering the long-term impact on the ecosystem and the community. This holistic approach ensured ecological balance, preventing over-exploitation and fostering biodiversity. The Lakota concept of Maka Ina (Mother Earth) or the Anishinaabe understanding of Aki (land/earth) as a relative underscores this deep, familial bond.

The arrival of European colonizers shattered this delicate balance, introducing a worldview utterly alien to Indigenous peoples. Driven by expansionist ideologies like the "Doctrine of Discovery" and later, Manifest Destiny, European powers asserted their right to claim "unoccupied" lands, conveniently ignoring the thriving civilizations that had stewarded these territories for millennia. They saw vast, "untamed" wilderness ripe for conquest and conversion into private holdings. This fundamental clash of perspectives—communal stewardship versus individual ownership—became the bedrock of centuries of conflict, dispossession, and genocide.

Treaties, often signed under duress or through deceptive means, became instruments of land transfer, frequently misunderstood by Native signatories who believed they were agreeing to shared use or temporary arrangements, not permanent relinquishment of their ancestral domains. The infamous "Trail of Tears," the forced removal of the Cherokee and other Southeastern tribes in the 1830s, epitomized the brutal enforcement of this new paradigm. Millions of acres, sacred sites, and ancestral homes were seized, transforming Indigenous nations from self-sufficient land managers into displaced populations confined to ever-shrinking reservations.

Perhaps no policy better illustrates the Western attempt to dismantle Native land ethics than the Dawes Act of 1887 (General Allotment Act). Its explicit goal was to assimilate Native Americans by breaking up tribally held lands into individual allotments. The architects of the Dawes Act believed that by forcing Native people into private land ownership, they would abandon their communal traditions, become "civilized" farmers, and embrace American individualism. The results were catastrophic. Over two-thirds of the remaining Native land base—approximately 90 million acres—was lost between 1887 and 1934, either through forced sale of "surplus" lands after allotment or through individual Native owners being swindled out of their parcels. This act not only drastically reduced Indigenous land holdings but also fragmented remaining tribal territories into a complex checkerboard of ownership, creating immense challenges for governance and resource management that persist today.

Despite these systematic assaults, the Indigenous connection to land endured, often serving as a potent symbol of cultural survival and resistance. Reservations, while products of immense injustice, paradoxically became spaces where traditional land ethics could be preserved and adapted. Here, communities could continue to practice elements of communal living, maintain spiritual ties to specific landscapes, and assert their inherent sovereignty over their remaining territories. The fight for land became synonymous with the fight for cultural identity and self-determination.

In the modern era, the clash over land ownership continues to manifest in various forms. Battles over resource extraction—mining, logging, oil and gas pipelines—frequently pit corporate interests and government agencies against Indigenous communities determined to protect their ancestral lands and waters. The Standing Rock Sioux Tribe’s struggle against the Dakota Access Pipeline, the persistent fight to protect the sacred Black Hills from mining, or the efforts to safeguard Bears Ears National Monument from development are prominent examples. These contemporary conflicts highlight the ongoing disregard for Indigenous perspectives, where the land is still primarily viewed as a source of profit, rather than a living being deserving of protection. As Winona LaDuke, an Anishinaabemowin activist and leader, powerfully states, "We need to understand that the land is not a resource, but a relative."

Beyond the material struggle, the spiritual dimension of land ownership remains paramount. Sacred sites—mountains, rivers, forests, burial grounds—are not merely places of worship but living repositories of history, culture, and identity. Their desecration by development or tourism represents a profound wound to the collective spirit of Indigenous nations. The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) of 1990 was a landmark step towards recognizing and protecting these spiritual connections, but much work remains to be done.

Today, Native nations are increasingly asserting their sovereignty and traditional land ethics on their own terms. Through legal battles, land trusts, and grassroots movements like "Land Back," Indigenous communities are working to reclaim ancestral territories, restore ecological balance, and implement traditional forms of governance. The "Land Back" movement, for instance, advocates for the return of Indigenous lands to Indigenous stewardship, recognizing that Indigenous management often leads to greater biodiversity and ecological health. This movement isn’t just about property; it’s about justice, self-determination, and healing.

The enduring wisdom embedded in Native American perspectives on land ownership offers crucial lessons for the entire world, particularly in an era of accelerating climate change and environmental degradation. The Western model of limitless exploitation has pushed the planet to the brink. Relearning the principles of stewardship, reciprocity, and interconnectedness—understanding the land as a relative, not a resource—is not merely an act of historical redress; it is a vital blueprint for a sustainable future. It calls for a fundamental shift in consciousness, urging us to listen to the oldest voices of this continent, those who have always known that true wealth lies not in what one owns, but in how one cares for the shared home of all life. The path forward demands respect, recognition, and a willingness to learn from those who have always been, and continue to be, the true guardians of the Earth.